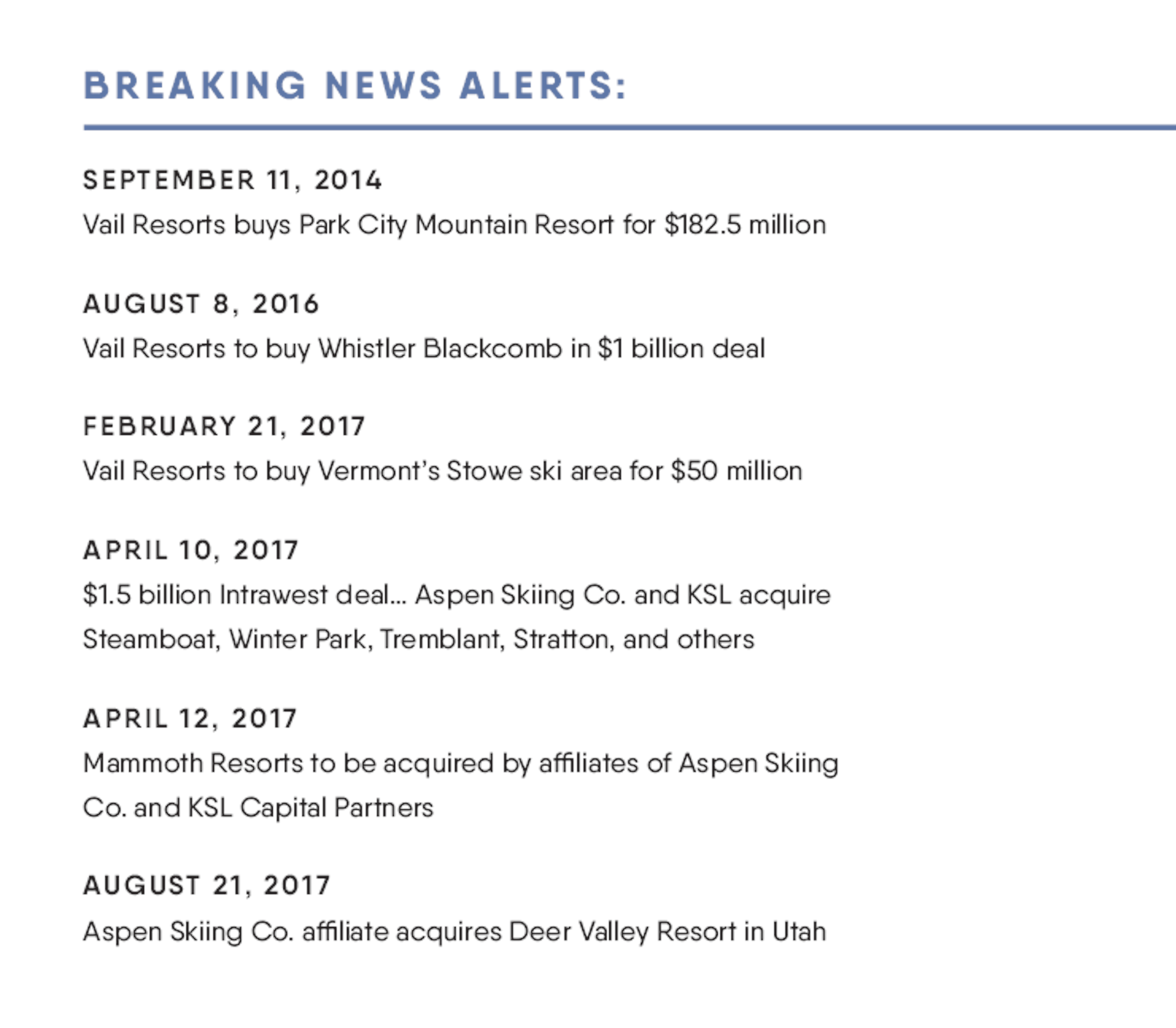

As with other large industries, the ski industry has felt the steady force of consolidation during the last several years. Whereas economist and author Adam Smith would refer to this as the invisible hand, most others would describe this force by name: Vail Resorts. Already the largest operator of North American ski resorts in 2014, during the next two years Vail shrewdly bought the two most consequential destination resorts it didn’t already own—Park City, Utah and Whistler Blackcomb, British Columbia. With these additions, Vail’s role as the singular empire in skiing, as the company that dictated terms to not only skiers but also to other resorts who sought those skiers, seemed set.

But just as Vail’s utter dominance seemed assured, a new player emerged this spring by making a series of moves that created a worthy, if not quite equal, rival to Vail’s collection of resorts. A Denver private equity group, KSL Capital, teamed with the Crowns, a Chicago family who owns the four mountains that comprise Aspen Snowmass, to buy Intrawest, a resort operator whose major holdings include Colorado’s Winter Park and Steamboat.

Two days after the Intrawest deal was announced, the new entity said it had also acquired Mammoth Mountain and three smaller ski mountains in California. In August, filling its Utah void, the company acquired Deer Valley, the skiers-only resort in Park City that’s long been known as one of the best operators in the industry. The newly formed and yet to be named resort company also includes Squaw Valley Alpine Meadows, California, which KSL already owned. The company clearly wants to emulate the path taken by Vail Resorts, a public company whose stock has nearly quadrupled in price during the last five years, valuing it at $8.7 billion.

Of the 27 or so major destination resorts in western North America, 18 are controlled by Vail Resorts, KSL or Aspen Skiing Co. If consolidation continues to creep, the world of skiing will start to resemble that of telecom, with two or three main choices—to which go pricing controls—and a smattering of regional options.

The Crown-KSL foray has roiled an industry that had found an uneasy, albeit fleeting, equilibrium. On one side, there were major independent ski resorts, including Whistler Blackcomb and Mammoth, who joined together to offer the Mountain Collective Pass, which, at $489, gives skiers two full days plus 50 percent discounts on additional days at a basket of more than 14 independent destination resorts. On the other, there was Vail’s deep lineup of destination resorts joined together by its Epic Pass, which grants holders full unlimited skiing at 15 mountains for $859.

For locals who tend to ski one mountain, choosing a pass has always been easy: buy the one that includes the local resort. For destination skiers, however, who generate more lucrative margins and periphery business—lodging, rentals, food—for ski resorts and are thus more sought after, the choice has grown more complicated. Buying individual lift tickets remains an option, but Vail Resorts in particular has made this route punitively expensive: one-day tickets at some of the company’s top-tier mountains hit $189 last season.

This leads many skiers to make a choice that determines where they will spend their ski holidays and their money. As Vail Resorts grew, so did the portfolio of the Mountain Collective as independent resorts sought to challenge the Epic Pass. Skiers who planned a destination trip to Aspen for Christmas would buy the Mountain Collective Pass and, if they put another trip on the books for February or March, would pick another Collective resort such as Jackson Hole. Likewise, skiers traveling to Vail or Breckenridge for the holidays might combine that with a spring trip to another Vail Resort such as Park City.

Vail has also purchased three regional ski hills in the Midwest close to major metros, such as Wilmot Mountain near Chicago, to steer skiers from these locales into the Epic Pass. Vail also bought Vermont’s Stowe, perhaps the most recognizable name in the East, to get more New York and Boston-based skiers into the Epic fold.

The calculus of which ski pass to buy remains roughly the same for the upcoming winter as it has been. But what will happen after that, and whether this congealing of resort groups will be good for skiers is debatable. Two titan resort groups competing with each other to sell season passes could lead to a price war—a situation that would benefit most skiers. This kind of thing has happened before, most notably in the late 1990s, when three publicly traded companies, Vail Resorts, American Skiing Co. and Intrawest, all with major properties in Colorado, fought for Denver-area skiers with lower and lower pass prices.

But there also exist many examples where duopolies don’t benefit consumers. Cable and telecom come to mind immediately, as many consumers throughout the country are limited to one or two providers who don’t fiercely compete on cost and instead bundle services and channels together to increase most package prices. Relief for consumers has only come recently, as more content options via the web have become available. In the airline industry, a decade of consolidation has resulted in just four major carriers—down from eight 10 years ago. Airlines, in turn, have been enjoying record profits for several years, even as customer satisfaction levels have declined.

Following the Intrawest and Mammoth acquisitions, most observers reasonably assumed that an umbrella ski pass covering Intrawest-Mammoth-Squaw-Aspen would emerge by the winter of 2018-2019. However, the Intrawest-Mammoth resorts are owned by a different company than that which owns Aspen. As of the publishing date, there is no agreement between KSL and Aspen; as of now, the new ski pass wouldn’t include the Aspen properties, which would be the pass’s clear headliners.

“Essentially right now they’re a competitor,” says Aspen Snowmass spokesman Jeff Hanle, referring to the new resort group.

Hanle did say that Aspen Snowmass would “probably” be part of a larger discussion about a bigger or different joint pass. Other industry insiders say that Aspen’s ownership is angling for a better valuation and terms from KSL, and is holding back on a new pass to get them.

David Perry, who will pilot the new resort company as its COO and President, is leaving the door open for future agreements with Aspen as well as other independent resorts. Perry was previously Aspen Skiing Company’s COO.

“Just as we surprised people by buying Mammoth and Deer Valley, we might surprise people in how we do things,” Perry says.

Perry has indicated that his group will do less macro-branding across its resorts compared with the practices of Vail Resorts, which has stressed its overall property umbrella and its Epic brand at all of its properties.

Whatever the case, the picture beyond 2017-18 remains somewhat muddled for skiers. The good news, of course, is that we’re only required to buy ski passes one year at a time.

There will be those who lament the loss of independent resorts, of their quirkiness and individuality. But it’s also true that Vail Resorts has proven itself a deft operator that almost always improves the properties it buys, making them more accessible, more family-friendly and adding better amenities and food options.

This flurry of mergers and acquisitions activity winnowed an already-small raft of major independent North American ski resorts, a group that includes Jackson Hole, Telluride, Snowbird and Sun Valley.

Wade Martin, the chief revenue officer of Powdr, a Park City-based operator of ski resorts including Copper Mountain and Mt. Bachelor, sees opportunity for smaller resort operators and independents that fill local niches.

“So much of the consolidation has been focused on the destination skier, but we focus on the local skier,” Martin says. “By creating the local experience first, we think the destination visit will follow.”

Copper Mountain, now the lone destination resort in central Colorado not attached to Vail or Crown/KSL in some way, would certainly be an interesting target for the KSL group were it looking to gain another carrot to entice Denver-area skiers. Such a deal could include Powdr-owned Eldora, a favorite of Front Range families looking for day trips without the headache of I-70 traffic.

Assuming that Aspen and KSL do put together the pieces for an over- arching pass, it would likely end these resorts’ participation in the Mountain Collective. The remaining Collective anchors would be Jackson Hole, Telluride, Snowbird and Sun Valley. The high point of the Collective, which once included Whistler, Aspen, Squaw Valley and Mammoth, would be long in the past.

“If the Aspen group does decide to take off and go their own route, it’s going to leave a big hole,” admits Jerry Blann, Jackson Hole’s president.

Blann says Vail has executed well on its corporate expansion, but he points out that skiing is ultimately a personal endeavor.

“Skiing is not about big corporations or big groups of ski resorts,” he says. “It’s individual, it’s aspirational and it’s personal. To me, it’s all about the ski areas, not the amalgamation, and that’s what we think elevates Jackson Hole.” The big spenders at ski resorts, the people whose behavior drives the tactics and decisions made by people at KSL and Vail, still include a wide swath of baby boomers. The rest of the balance is mostly made up of people who are 35 to 50 years old. Millennials have yet to command the full attention of ski resort operators.

But they will. And it’s this generation that has been marked by a clear preference for artisanal experiences: craft beer, artisanal food, off-the-trail vacations. It would follow that this generation would prefer that its ski resorts be singular, quirky and unique. The question: will there be any of these places left?

![[FIRST LOOK] New 2027 Skis and Outerwear From Rossignol](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1771280782-2026_fs-firstlook-deck.png?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)