Nothing prepared Jessica Polich for the moment Glen Plake arrived at Ski Brule. Two days before New Year’s 2006, the operations manager at the 500-foot vertical, 150-acre Michigan ski area was going about her business when a 38-foot Freightliner rig plastered with Plake’s likeness pulled into the parking lot. There hadn’t been a word of warning. “I felt like a sixteen-year-old girl,” she says. “Glen Plake had always been a hero of mine.”

As soon as the red, white and blue truck rumbled to a stop, it was mobbed by a dozen kids. Just a few minutes later, America’s best-known skier stepped out, flashed a toothy grin, grabbed his skis and led the whole pack to the slopes like some Jack Frost Pied Piper. Plake and his wife Kimberly spent the next two days riding lifts with locals and hanging out in the lodge, where he explained he’d found a brochure for the resort at a nearby gas station. He signed a poster for every kid in the Iron River, Michigan, region and led the New Year’s Eve torchlight parade. When he saw four- and seven-year-olds dancing on the tables at midnight, he told Jessica, “You know what, this place is awesome.” Whether the party would have had the same energy without the ski celebrity is an open question, but both he and Ski Brule passholders are still talking about that night 12 years later.

Welcome to Glen Plake’s annual Down Home Tour, the largely unsponsored, completely unplanned and utterly grassroots annual tour of America’s smallest ski hills. Most winters, the icon of 1980s ski films and the longtime face of K2 and now Elan skis spends a month or two on the road with his wife in their custom rig visiting resorts not found on the Epic or Ikon passes. They set their route according to whim, weather and a simmering desire to visit every ski area in America—Plake estimates he’s skied at some 200 so far. He’s a bit too modest to say that the tours are his gift to the skiing public, but most of the resorts he visits see it that way (he doesn’t charge them a dime). It’s also obvious that in the era of resort consolidation, local resorts need all the juice they can get. Closer to the truth is that Plake loves being the center of attention just as much today as on that famous afternoon in 1988 when he glued his mohawk into a gold fin and goofed around downtown Chamonix filming The Blizzard of Aahhh’s.

If you aren’t one of the thousands of people who have hung out with Plake on the Down Home Tour at resorts like Ski Brule; Anthony Lakes, Oregon; or Trollhaugen, Wisconsin; you’d be forgiven for assuming he remains the brash bad boy his haircut implies. His past is indeed checkered. Starting in his teenage years, there were a series of arrests and jail time. When he flew to Chamonix in 1988 to film Blizzard, he actually skipped a scheduled trial—he was planning never to return. Plake was such a hit, however, that Blizzard filmmaker Greg Stump paid his fines and legal fees so he could do promotional work back home.

There was legendary binge drinking like the morning in 1992 when he woke up in the Jackson, Wyoming, jail charged with three felonies after a ski patrol party that got a little out of hand. He was dropped by his sponsors and knew he had to clean it up. “I realized that there wasn’t any skiing in jail, at all, so I quit drinking,” he says. By then he had met his now wife and former New York-based model Kimberly at a promotional event at Stratton Mountain, and the two were married a few years later. He credits Kimberly for helping him stay sober. “I really don’t miss alcohol,” he says.

The Down Home Tour was his literal road to career redemption. The first one, in 1991, actually served as his honeymoon. Plake and Kimberly visited 50 ski areas in 33 states, logging an epic 13,000 miles in 68 days in a pickup towing a flimsy trailer. He loved the small ski hill limelight and the people he met so much that when he needed to recoup his sponsors, rebooting the Down Home Tour was an easy choice. It didn’t feel like walking in the wilderness to him. It felt like fun. Along the way, in places like Iowa’s Holliday Valley and Beech Mountain, North Carolina, he encouraged fans to write to his then sponsors K2 and Raichle. Eventually the tide of fan letters lifted him back to their good graces.

By now, the tour has become ritual. The smaller the resort, the better. He and Kimberly never set a schedule, and they never call ahead to say they are arriving. “I like spontaneity,” says Plake. After a string of terrible vehicles, he had the Freightliner customized in 2006 with diesel heaters, a full-sized bedroom, bath and kitchen. There is even a workshop on the lower level with a separate barn door entrance.

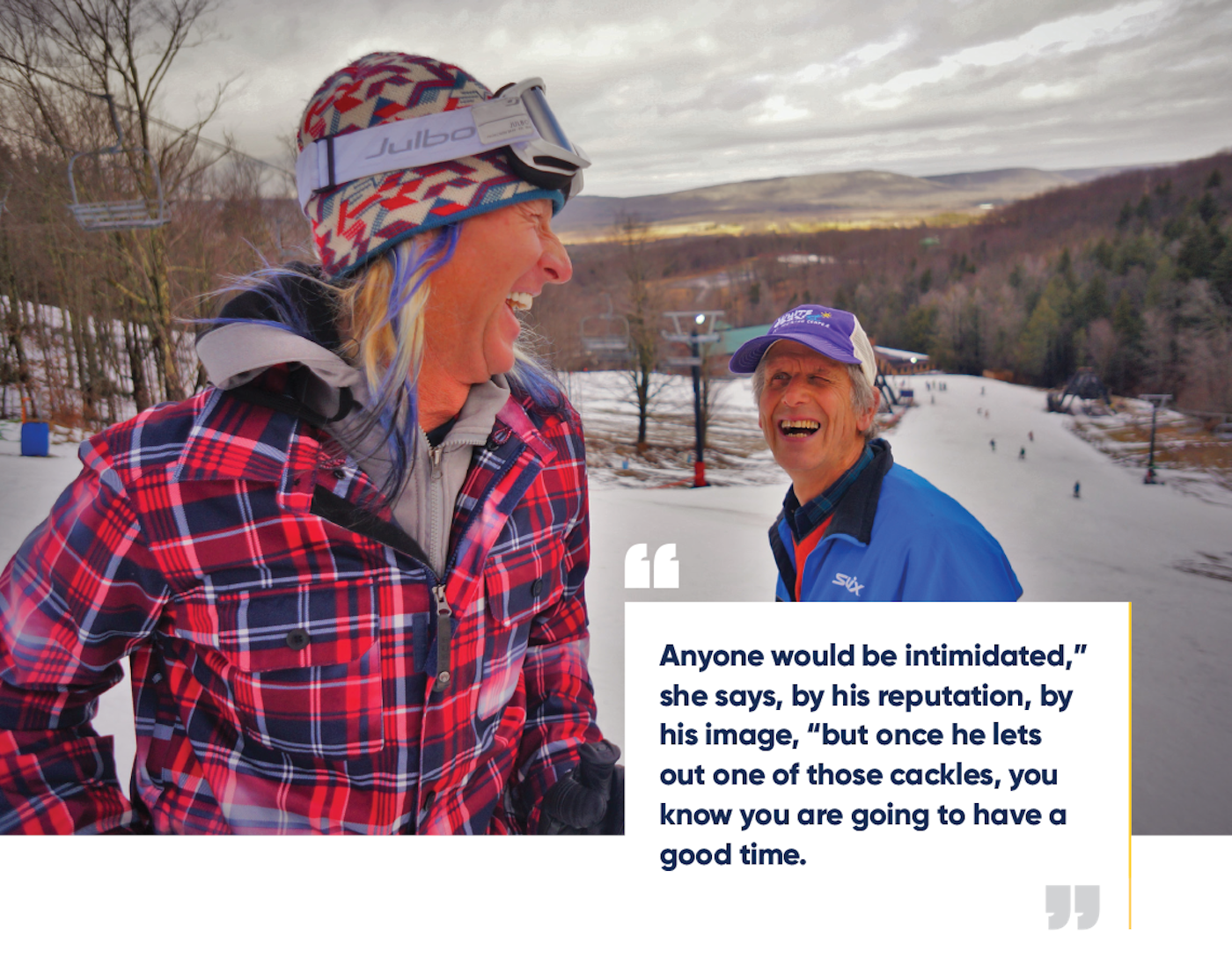

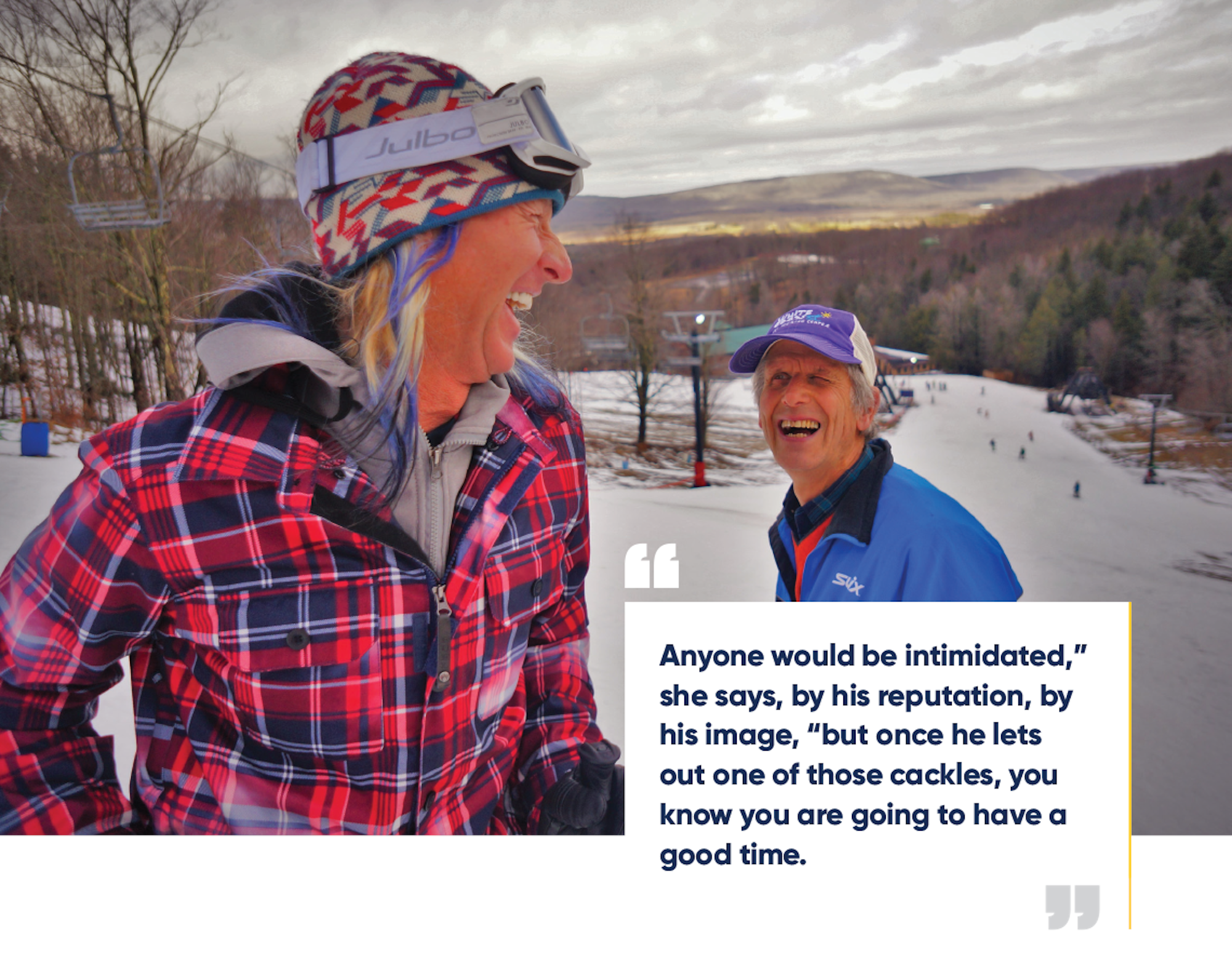

The Down Home Tour is also remarkable for how little he actually erects the mohawk to full height. (Almost never on the Down Home Tour, and a dozen or so times a year for the biggest events like trade shows.) To connect, he relies instead on his native and tireless extroversion. “Hi, I’m Glen,” is his invariable greeting, whether or not he is recognized. “He’s the same guy whether he is talking to an eight-year-old, an eighteen-year-old or my eighty-year-old mom,” says Greg Wozer, VP at Leki USA and a friend of Plake’s for decades. “He can make anyone feel they are the most interesting person he knows. Once you make eye contact with Glen, he is locked in.”

Kicking it in the Ski Brule cafeteria, the kids loved him, as did Jessica’s 93-year-old father-in-law, one of the resort’s original founders. “They spent a few hours together, just talking about the history of skiing,” says Polich.

Then there is the skiing of course. He skis with anyone who will stand in the lift line with him, sometimes rolling 30 deep, like the time at Stevens Pass, Washington, when he convinced ski patrol to let his entire entourage duck the rope to hit the secret stash they wanted to show him. Or the worm turn and slow dog noodle clinics that evolve into spontaneous freestyle competitions like in Waterville Valley, New Hampshire. Or the night he trained gates with the Trollhaugen ski team in Wisconsin after the coach invited him to drop by. “If I schedule out the whole tour, I miss things like that,” says Plake.

Sue Haywood skied with him and a handful of friends last winter at Canaan Valley, West Virginia, on a blustery March day with what little snow the resort had melting fast. “Anyone would be intimidated,” she says, by his reputation, by his image, “but once he lets out one of those cackles, you know you are going to have a good time.” It turned into a virtual Professional Ski Instructors of America (PSIA) clinic, where he taught them to find the balance point of the ski and to maximize glide. “All we are doing is sliding on snow,” he told them. “This is fun.”

It’s the sort of attitude that wins Plake a lot of fans. Like the time at Ski Liberty, Pennsylvania, a few years ago, when a guy showed up with a pink jacket with Plake’s signature on it from 1991, which Plake promptly signed again. Or the shrine of signed Plake posters at Sirriani’s in Canaan Valley, where they also have a menu item called Glen Plake’s Extreme Garlic Chips, created at Plake’s suggestion. Or the 300 or so people who showed up at Kissing Bridge in Buffalo, New York to celebrate Glen Plake Day, with an official proclamation by the Buffalo mayor. “The mayor didn’t even know how to ski,” says Wozer. “Glen’s reputation goes so deep, a bunch of people must have told him he had to do it.”

Plake is far from the has-been rockers booking gigs on the heartland casino circuit to milk their fading fame, however. He continues to evolve impressively. He and Kimberly spend much of the year in Chamonix, where Plake still notches personal firsts on the valley’s notorious test piece ski and mountaineering routes. He is also pursuing the infamously rigorous IFMGA mountaineering and ski guiding certifications so he can guide others on those routes.

Even more interesting is his latest role—reality television host of the History Channel’s Truck Night in America. His lifelong penchant for working on cars and a parallel, largely amateur career in off-road racing qualified him as one of four hosts on the program featuring customized trucks and their owners put through a series of contests. Probably more important in landing the gig, which wrapped filming its second season in the fall of 2018, was the profuse personality he has honed in four decades of public appearances at ski resorts worldwide.

“Glen is one of the best ambassadors skiing has ever had,” says Jeff Mechura, who worked with Plake for years at K2, and is now vice president of global marketing at Elan, Plake’s current sponsor. “He has learned how to connect with every single person he meets. That’s what makes the Down Home Tour important—it gets to the heart of skiing, having fun with friends and family on the mountain. Plake is the number one spokesperson of having a good time.”

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Limited Edition FREESKIER Hat](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1772568976-3x4a9169.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)