If you followed Salt Lake City based @BrodyLeven on any of his social channels this spring, you already know that he’s been bagging gnarly ski descents around the world, from Iceland to Romania to his backyard of the Wasatch. It just so happens that his next big adventure will be summitting and skiing the 20,320 foot Denali—the highest peak in North America. We caught up with Brody one day and a half before his departure to talk about his winter, his thoughts on ski mountaineering and his upcoming expedition to Alaska.

Q&A:

Hey Brody, what’re you up to?

I am scraping to get everything together for this Alaska trip. I’ve just been gone for, like, three months and I come back here and I have, like, two weeks to totally do all of my editorial stuff for this entire season, to prepare for the most gear-intensive trip of all time and decompress… and put out media from this last year. It has just been so much in such a short amount of time.

Can you talk about the Denali trip? How did it come together?

The season that I focus on really begins in April, because that’s when ski mountaineering really kicks off. Like everyone else, I love skiing powder. I live in Salt Lake City, I ski powder all winter, but once the snow starts melting is when I get stoked because I can start skiing the stuff that I’ve been thinking about all year.

I was just about to leave for Iceland a couple of months ago, and a good friend of mine named Max Lowe hit me up and said he was doing a Denali trip with his dad, [the world-famous] Conrad Anker, and the team was in flux at the time. Since then, it’s become a really cool, diverse team of athletes and outdoor industry people, including a bunch of people that I really, really look up to more than pretty much anyone else. Jeremy Jones is going, who is on the O’Neill team with me, so I’m pretty psyched on that because I’ve gotten to work with him on a couple of different projects, but they’re usually for more media stuff—to do something that’s like soul skiing with him is pretty cool. And to do something also that’s a challenge for both of us, because I think it’s hard to give someone like Jeremy Jones or Conrad Anker a challenge in the mountains. To go do something that I know is not easy for anyone, that’s a good feeling.

It’s a huge honor for me to be asked on a trip with such elite athletes. Jon Krakauer is coming. I’m psyched, he’s my favorite author. I can really appreciate the seemingly random nature of this team of athletes, but at the same time it’s pretty cool how collective it is, in a sense that I don’t know if anyone knows everyone on the team, but everyone knows some people on the team, and I think that can be viewed as irresponsible if it wasn’t an experienced and trained group of mountain people.

When do you leave for Alaska?

Day after tomorrow. It’ll be a total of fourteen days or something like that since I got home from a three-month-long trip.

What’s your travel itinerary for the next couple of days/weeks?

I fly straight to Anchorage in the morning [6/6/2013]. There’s a food team that’ll arrive on the 5th to take care of most of our food logistics in Anchorage. I’ll arrive the next day along with a bunch of other people. It’s a fourteen-person team, it’s a large expedition. Some people will arrive on the fifth, some on the sixth, some on the seventh, we’ll get together and do a big gear shakedown: make sure all of our food, fuel, gear is in order. Then we’ll take a shuttle to Talkeetna, which is the launch point for most Alaska Range expeditions. We get an orientation through the park service in the Talkeetna ranger station. It’s cool for the less experienced people such as myself. Talkeetna itself is a historic place in the mountaineering world. I went there with my family a couple of years ago after my college graduation and I knew the names of all the mountains and all of the air taxi services and everything because I’ve spent my life reading about this town and the stuff that’s accessible from it.

So we do orientation with the park service in Talkeetna, and then as soon as we have a weather window we’re hoping to fly in on the eighth. You fly in on these little bush planes and they drop you off on the glacier with a month’s worth of gear and food, and from then on out you have to melt every drop of water that you use. You will not see a single tree or blade of grass for about a month. You get dropped off at about 7,000 feet and over the course of a week you’ll work your way up to base camp, which is at 14,600 feet. In between, you do various wave transportation but in general, you’re skinning with a huge backpack on, pulling a big sled with a big duffle bag in it. Everyone has a big backpack and a big sled and it’s roped up glacier travel for a week until you get to base camp. From there, you do acclimatizing missions to get higher and higher on the mountain until hopefully you go to the top and you ski off the top of that thing. Ski off the top of North America.

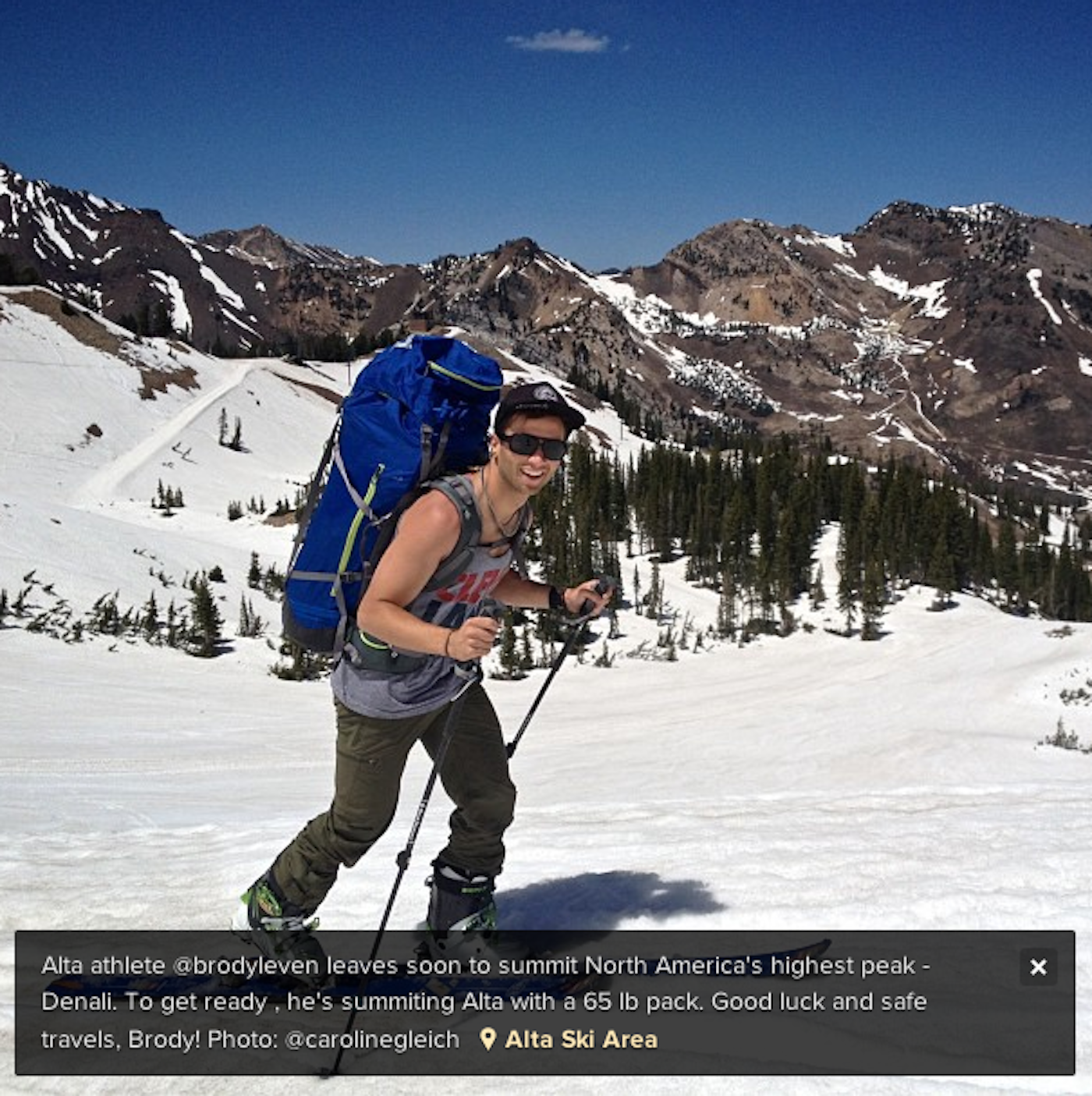

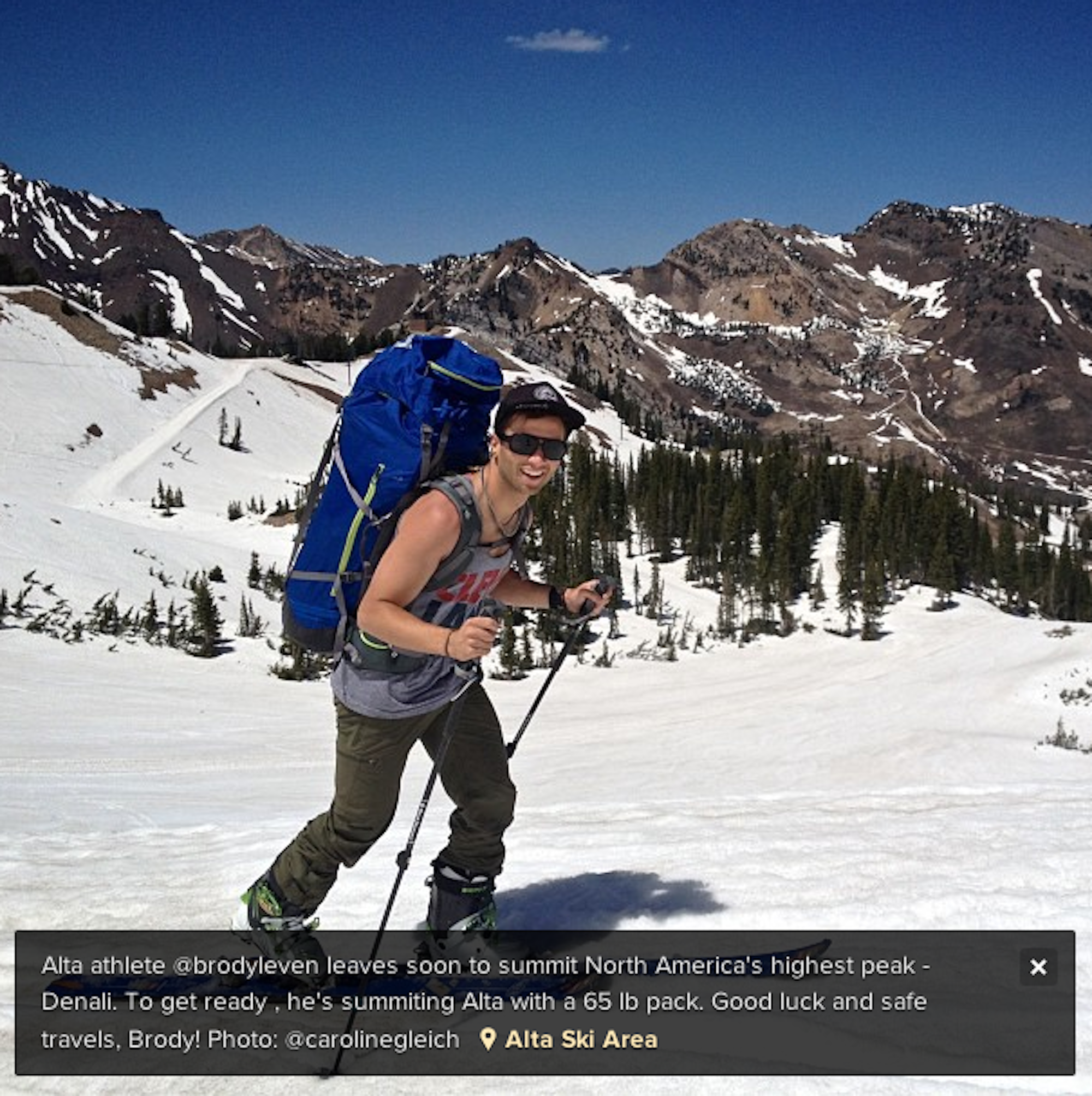

Alta recently shared a photo of you skinning up the ski area with a 65-lb pack on your back. How’re you training for Denali?

Brody Leven summits Alta with a 65-lb pack. Photo via @altaskiarea.

I guess I can speak to the “training” that’s gone into this. It’s the cliché of our sport, our training, because a lot of what you deal with on these trips is that your physical tolerance and pain tolerance have to be high, but so does your “suffer” tolerance. Going for a hike up Alta or going for a run or a bike ride is not going to really increase your suffer tolerance significantly for temperatures that are 40 degrees below zero. That’s what we prepare for is negative 40 degree temperatures. I just came back from this three-month trip that offered me what was going to amount to a lot of “technical training and physical training,” but I didn’t even know I was going to Denali at the time. I was just doing this trip, it’s not like I thought about it as training, that was not a means to an ends, that was an end in itself and that’s also how I see Denali. I tend to see a lot of things as an end in themselves, I’m not always looking for the next thing, I’m doing what I’m doing at the time, I’m living in the present.

Who’d you go on the Romania trip with?

I was with a photographer named KT Miller, and she is also going on this Denali trip coincidentally, but it was just the two of us in Romania. That ended up being very crucial, just to have two of us, because the logistics for skiing there were pretty difficult, as were the physical demands. We would take a cable car up a couple of thousand feet and then skin for a couple of hours to the top of a couloir, which I’ve never done before because I’ve never skied in Europe. You get to the top of a couloir and you’re like, “Alright, this will be mellow, I only skinned for 1,500 vertical feet for two hours, and now I’m going to drop down and ski back to the valley.” Well, these couloirs would be like 6,000 feet long and they would run out of snow half way down, so you’d end up walking 4,000 vertical feet and four hours in shoes, and that’s how every day went and we were doing first descents. It was a very physically demanding trip and more than just ski mountaineering—it was just a lot of practice with staying positive, a lot of practice with laughing at how miserable you are, but that’s the skiing that I love and that’s one more reason I’m looking forward to Denali.

Romania was great “training,” as was my entire winter. All I do is ski tour, so I’m ready in that regard. As soon as I got back from Eastern Europe, I got to Utah and just hit it hard for the last two weeks. I don’t want to be a weakness in the chain that is our team.

You’ve obviously been in the ski mountaineering scene for the past couple of years, but you’ve just recently entered the spotlight. What do you attribute this to?

Well, some of the companies that I’ve been able to work with recently have really helped me, but I think it’s been the collective nature of—ever since I’ve graduated college—I’ve considered building my career as starting a business. Like starting any business, it’s not going to be profitable for a couple of years, but I was looking forward, I was making investments in myself, in my business, in my brand and it’s finally working, it’s finally paying off. Yes, it’s been awesome getting attention from great companies: from GoPro, from O’Neill, from big companies both endemic and non-endemic. The non-endemic companies have provided me some more household exposure and then the endemic companies, like GoPro, can get you in front of a lot of people that like extreme sports.

I think the other thing has been, I’ve just been trying to be a content machine. I really see content as king and I’m not trying to wait a year before getting my story out in the next magazine, I want to be like, “Hey, I was here yesterday, check it out, this is what’s going on right now,” and through that I really try to get other people stoked and get outside… and get people to realize, “Hey, I can do something every day,” whether it’s after work or whatever it may be. In that way, I think the more content you push out, quality content, the more eyes you’re going to get in front of and there’s really no secret to that, that’s literally all I’m doing. If I don’t have something quality to push out then I’m not putting anything out there.

You mention not wanting to “wait a year before getting [your] story out in the next magazine,” but of course, media is changing, too. You’re a frequent contributor to various ski media outlets, including Freeskier. What are the advantages of this for you?

I think that I’m, like, the outdoor industries’ number one fan of inspiring content. I am on every blog and every website, every day. I eat that stuff up: all the alpine climbing websites, all the climbing websites, all the mountaineering websites, all the ski mountaineering websites, and all the regular ski websites. I just want to do my part to add to that content pool of quality stuff that people are being inspired by, and maybe they’re sitting at their desk at work, but whether they’re planning their weekend or it just makes them happy to read it, like, “Hey, someone’s able to get after it today, that’s cool.” In that way, I try to have really broad reach. I write for every major ski website, I’m trying to get in all the magazines, I’m trying to do the non-ski outlets, as well as staying up on social media and actually be outside every day. It’s not like being outside every day for me is just going to take a couple of runs through the park, my days outside end up being all day outside. I think that anyone starting a brand, it’s hard work. I’m just trying to make it work and I hope people like it because that’s really the only reason I do it. I’m not tooting my own horn, I’m just trying to make other people like it the same way I like reading their stories.

You get to ski with people you hold in the highest regard in the ski and outdoor industry. You mentioned Jeremy Jones. Who influences you to do what you do?

It’s interesting, because the skiing I do, I don’t want to pigeon hole myself and say, “I’m a ski mountaineer,” or “I’m a backcountry skier,” because I do a lot of really, really shitty skiing. For example, online, it causes people to be like, “That would be cool if there was snow in it,” or, “F that.” People just don’t like to do what I’m doing, but it’s obvious based on the feedback, that they love to read about it and look at pictures about it, which is cool because that’s what I like to do, and if other people like hearing about it, good. It doesn’t mean it has to inspire them to go out and walk for five miles over dirt to ski two hundred vertical feet, but maybe it’ll inspire them to go for a trail run or go for a mountain bike ride or go ski park.

It doesn’t mean it has to inspire them to go out and walk for five miles over dirt to ski two hundred vertical feet, but maybe it’ll inspire them to go for a trail run or go for a mountain bike ride or go ski park.

Yes, I look up to Chris Davenport, Jeremy Jones and Andreas Fransson and big ski mountaineer names, but I also find myself reading a lot more blogs of these alpine climbers. They’re so good at expressing their suffering, and I think that’s awesome because it’s the same thing I go through. It’s just awesome to see someone in a different specialty going through pretty much the exact same thing and expressing it so well. I focus a lot more on how much hell I go through than the ten seconds I get to actually ski down. It’s a lot of shared characteristics, a lot of rope work and those things, but just the prolific climbing blogs, like Cheyne Lempe, he’s like a 22-year-old alpine climber who goes to Patagonia and just slays, just puts up first ascents… then I look up to Andreas Fransson as he goes and skis those same things.

How has the mountaineering in Utah been?

It was good. I spend a lot of the season waiting until stuff is safe to ski, but in the meantime I go shred pow meadows and do laps just trying to get fit for the spring and summer. I love summer skiing so much. But Utah’s been cool, it provides an excellent training ground for me. But again, it’s not a means to an end, it’s an end in itself. I moved to Utah because Utah’s sick, not just because it trains me to go elsewhere.

Do you have a favorite line that you skied this year?

This year, this one first descent that I got in Romania encapsulated everything that I like in a line. We have yet to post pictures of it. It was a very, very steep face of the mountain that had a really thin strip of snow going down it, and when you looked at it from an opposing ridgeline, you had no idea if it was vertical, if it was a frozen waterfall, and if it was the width of skis or not. And it’s discontinuous, there’s lots of cliffs breaking it up. But, I went over to it one day and I looked down it and I’m like, “Yeah, I can ski this.” We later found out that it’s a popular winter climbing route. It’s a named couloir, but only because of the climbing route, not because anyone would ever go down it. That brought it all together for me, that was the first time that I was able to look down a line and be like, “Okay, I don’t know if this is skiable or not, but I know that I finally have accumulated the skill set to be safe in this line. Whether I can ski it or I have to get out of it or I have to rappel a hundred times or whatever. I’m confident in my ability to get down this thing safely.” That was all captured on film and pictures, which I’m pretty stoked to share eventually.

How did you get in to ski mountaineering?

I think as this explosion in ski mountaineering is hitting, backcountry skiing is the fastest growing segment of skiing, and rock climbing simultaneously is a very fast growing sport, especially in these outdoor towns like Salt Lake City or Boulder. I think that there is just a natural desire to combine them and especially as more and more of the ski mountaineering stuff, like the stuff that I do, is hitting mainstream and people are seeing it on a more regular basis, especially in the ski world, that people are going to try and rush into it.

I think having a really, really solid base of all these different mountain skills, whether it’s just winter camping, mountaineering, alpine climbing, rock climbing, ice climbing, steep skiing, like… dude, I use my park skiing skills. I grew up a park skier and I find myself in a super steep chute and it’s not the same width as your skis, you’re either doing some weird jump turns or you can just do a little backwards skiing through this little section, having these various skills is important. I’m on the younger end of the people that are actually trying to make it in ski mountaineering. A lot of young people, they get too bold and ski mountaineers die, so I’m trying to keep it really in check, my humility towards the mountains is very apparent and I’m trying to round out my skills. It’s not like I just go steep skiing every day, I’m out there rock climbing or ice climbing in order to round these skills out.

You don’t have to have some mentor like a lot of people look for. I was never able to find a mentor outside. You can just hone your skill set, but on a day that you’re going to ski something steep that’s all you’re doing, you’re skiing something steep. You’re going rock climbing, you’re just rock climbing. The more you do each of those things, the more you can combine them. I think having a really well rounded skill set and knowing how to implement it is the most important part and you can’t just step up to the lines that you hear about all of the time.

That’s why I recently posted that Terminal Cancer story on Freeskier. It almost got some hate. People were like, “What’s the big deal?” These guys are so used to seeing ski porn, and yeah, I ski way harder lines than that, and most people ski way harder lines than that, but there’s way more people out there being like, “Man, what’s the first step to going to Iceland and skiing a first descent?” That first step is not going to Chamonix and skiing a first descent, but maybe going to Terminal Cancer and booting for two hours. I try to share my stories that involve a variety of skill sets: I’ll share rock climbing stories, and then I try to share stories that involve a variety of difficulty levels as well. Because I’m nowhere near the top of the game, but it’s important to share stuff that pretty much anybody can ski. I think sometimes it’s better to have advice from someone who’s done it recently and also to get advice from someone who’s made a living doing it.

Also Watch: Freeskier checks in with Brody Leven at SIA 2013

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Head-to-Toe Ski Setup from IFSA](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765920344-ifsa.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Legendary Ski Trip with Icelantic's Road to the Rocks](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765233064-r2r26_freeskier_leaderboard1.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Head-to-Toe Ski Setup from IFSA](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765920344-ifsa.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)