Featured Image: Vincent Ledvina

Grand Teton National Park is a popular recreation area, no matter the season. While it’s hiking, backpacking and climbing in the summer, it’s backcountry skiing and splitboarding in the winter that summons so many to the 310,000 acres of public land. And although humans have been exploring the park for centuries, bighorn sheep have called this area home for thousands of years. Loss of habitat in the valley due to human development, disease, climate change, hunting and competition with non-native species are all contributing factors that have pushed the native herd to higher elevations—think, 10,000 feet—in the Tetons during the winter months. Now, with less than 100 bighorn sheep left in the entire park and isolated from other nearby herds, the threat of local extinction of these animals is imminent.

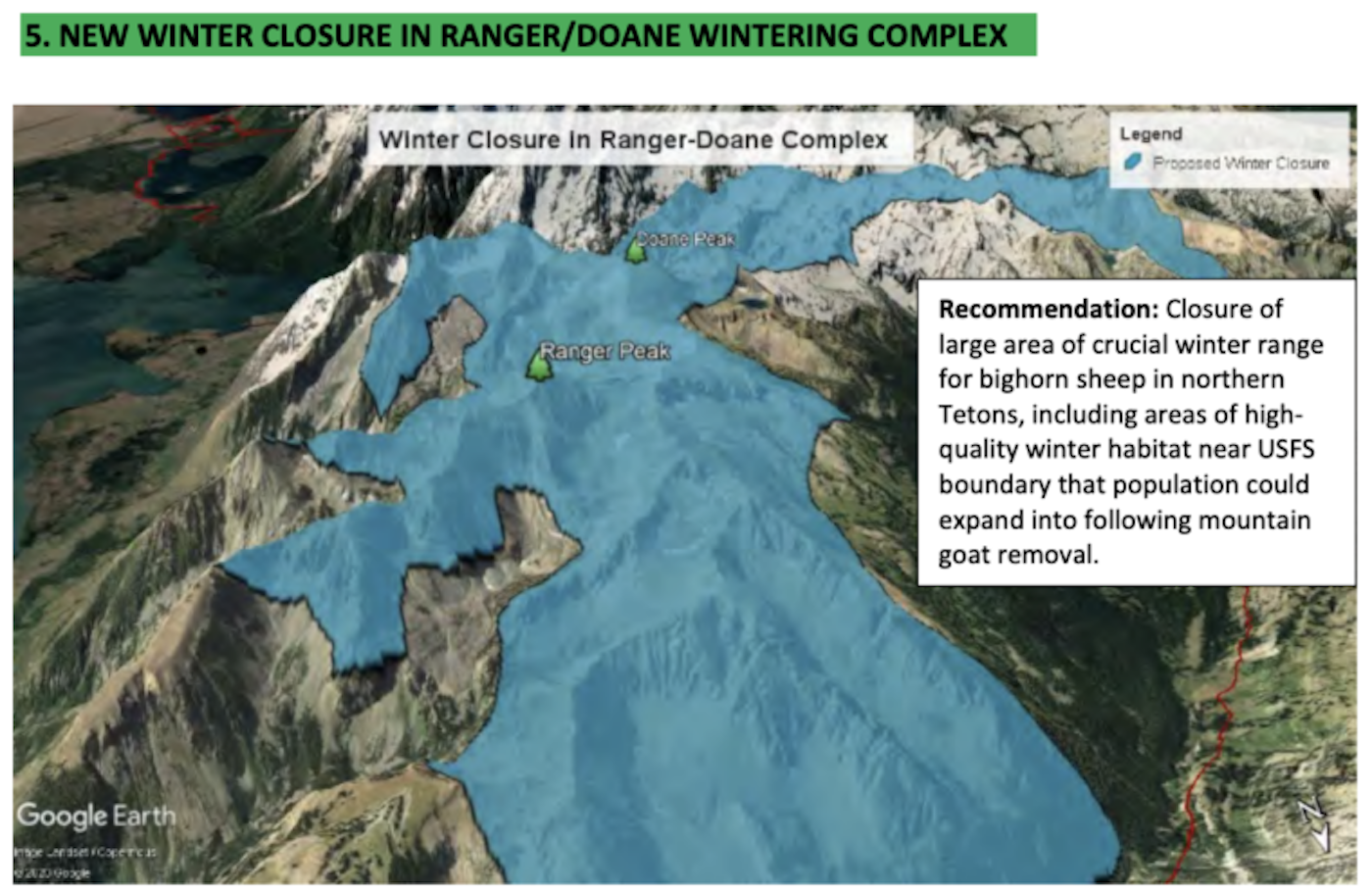

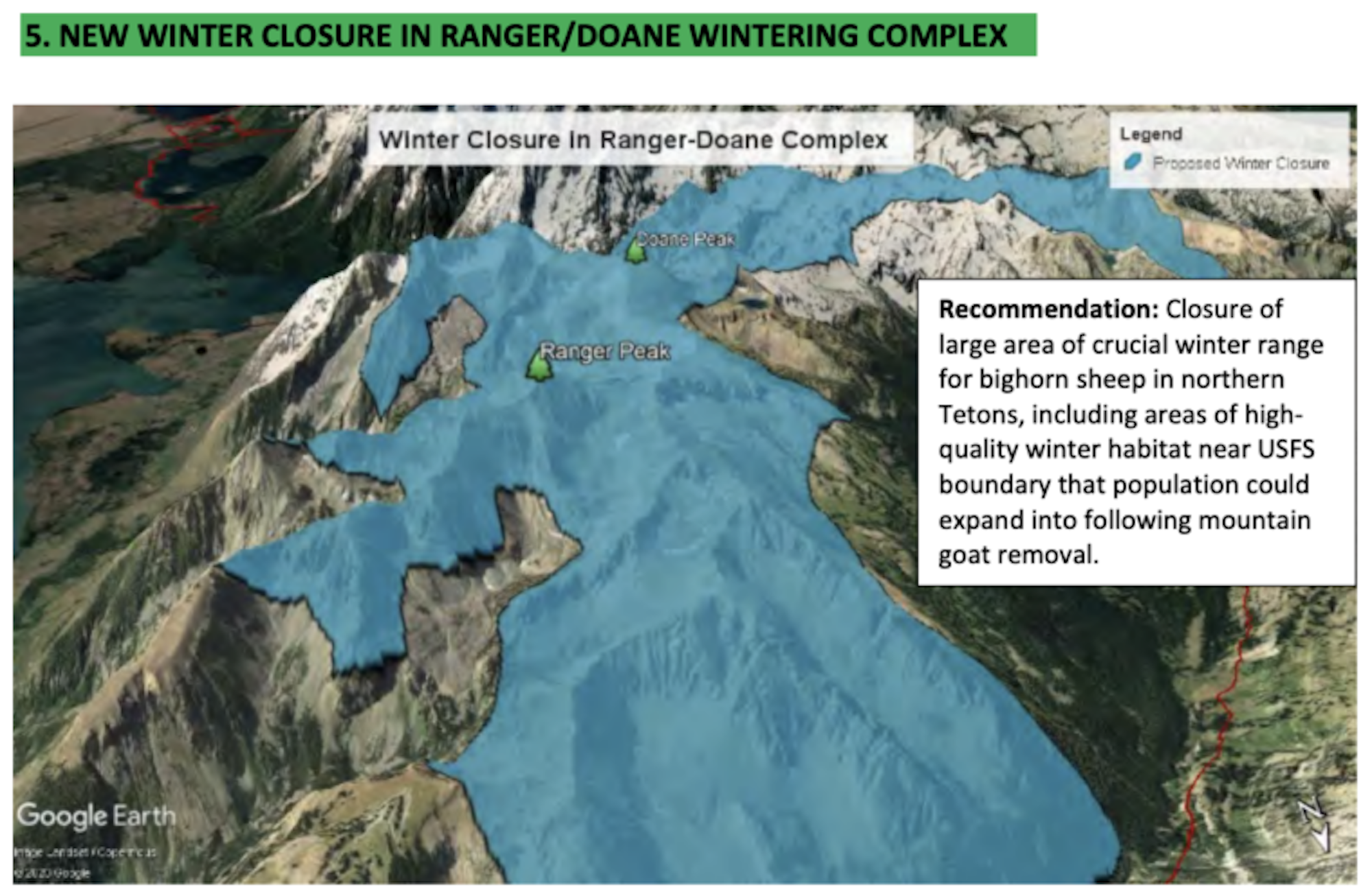

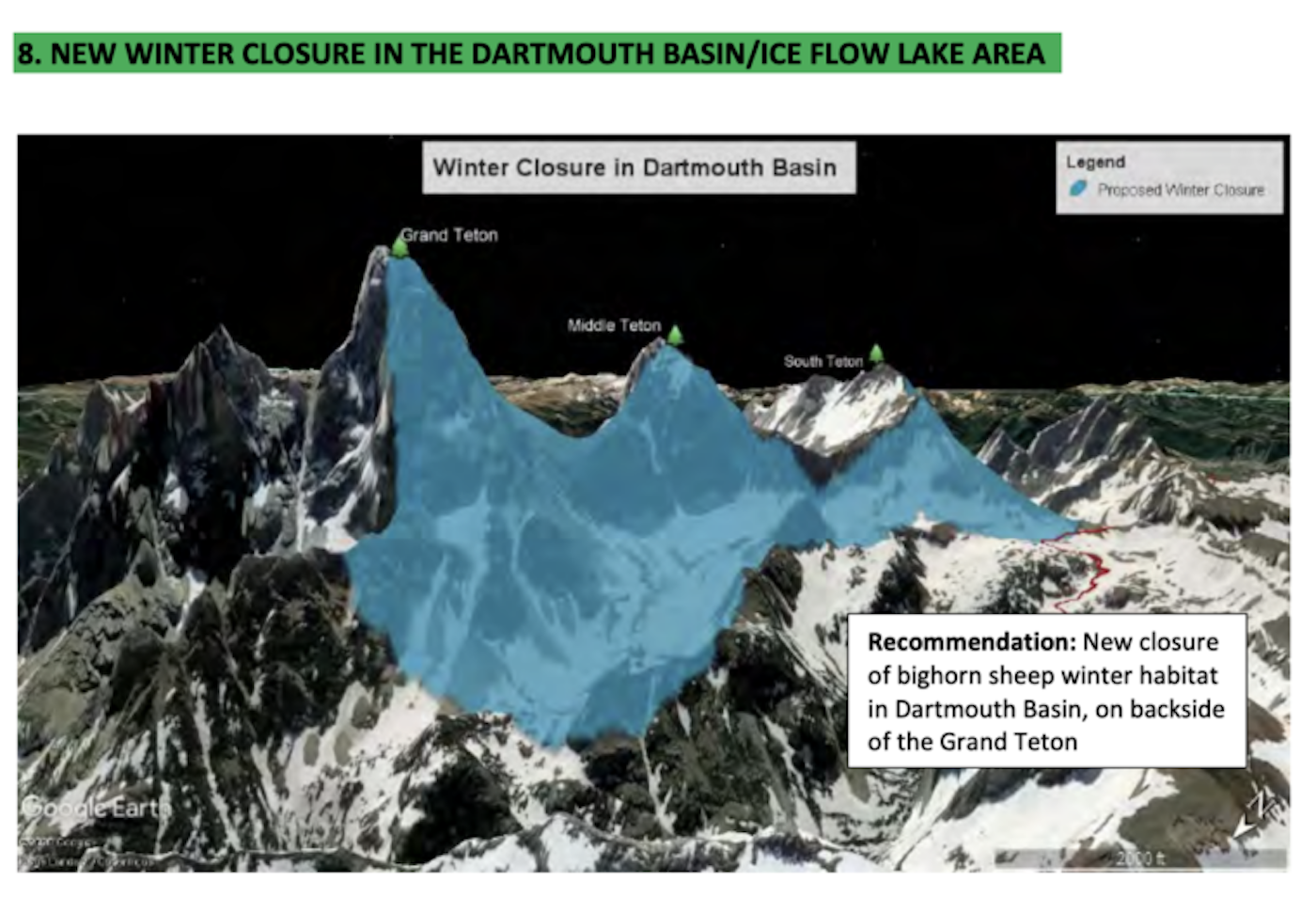

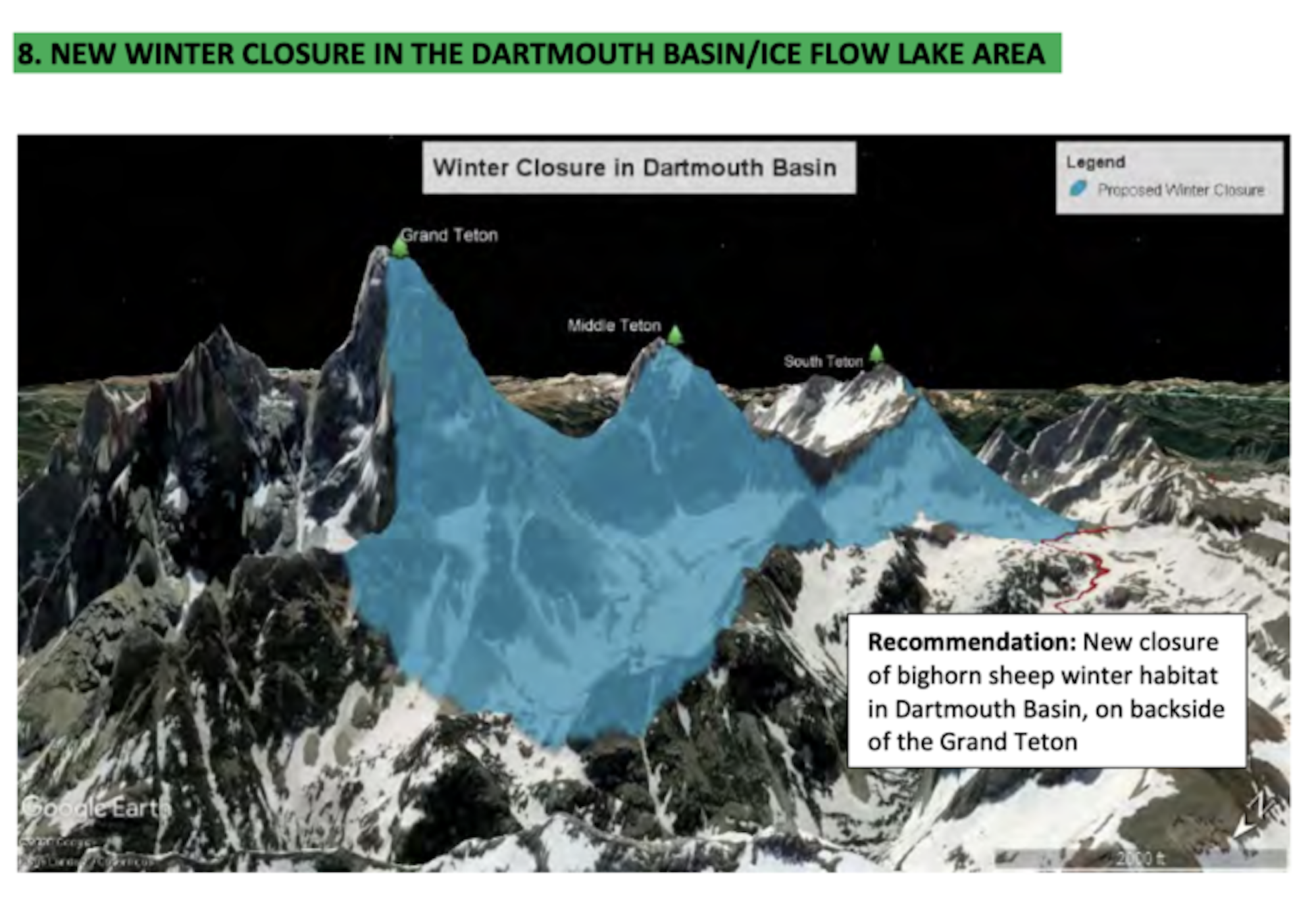

In an effort to protect and help the remaining bighorn sheep population thrive, an interagency group of local biologists called the Teton Range Bighorn Sheep Working Group (TRBHWG), along with community stakeholders, have developed a long list of recommendations through a multi-year collaborative process. In the 100-page document, there are the suggestions of closing popular backcountry skiing areas, including Avalanche Canyon, peaks in the northern end of the park and National Forest land surrounding Jackson Hole Mountain Resort and Grand Targhee Resort. The proposed closures are significant in size, and have rightfully garnered the attention of recreationists on both a local and national level—specifically those who like to frequent these areas on a pair of planks.

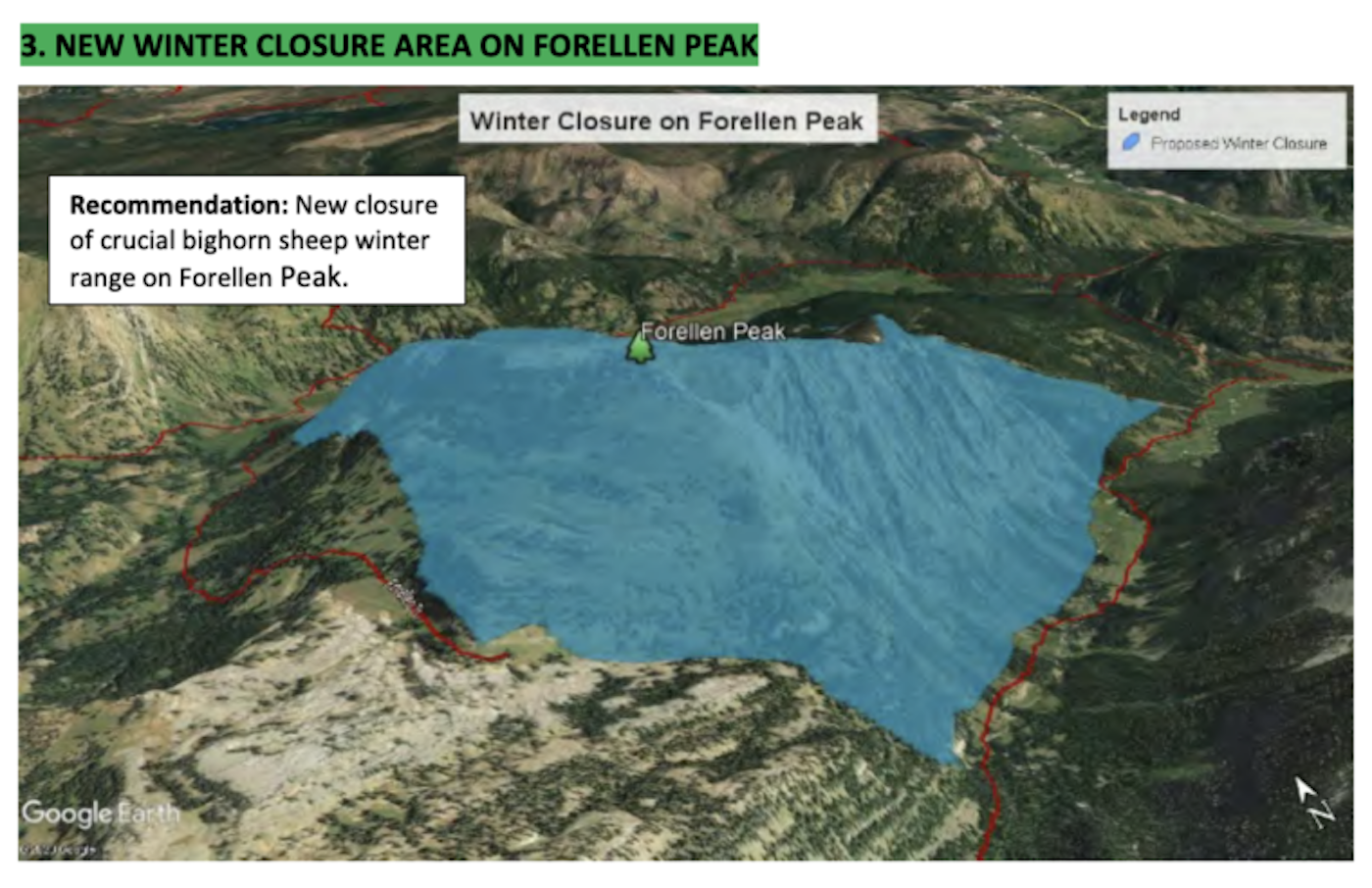

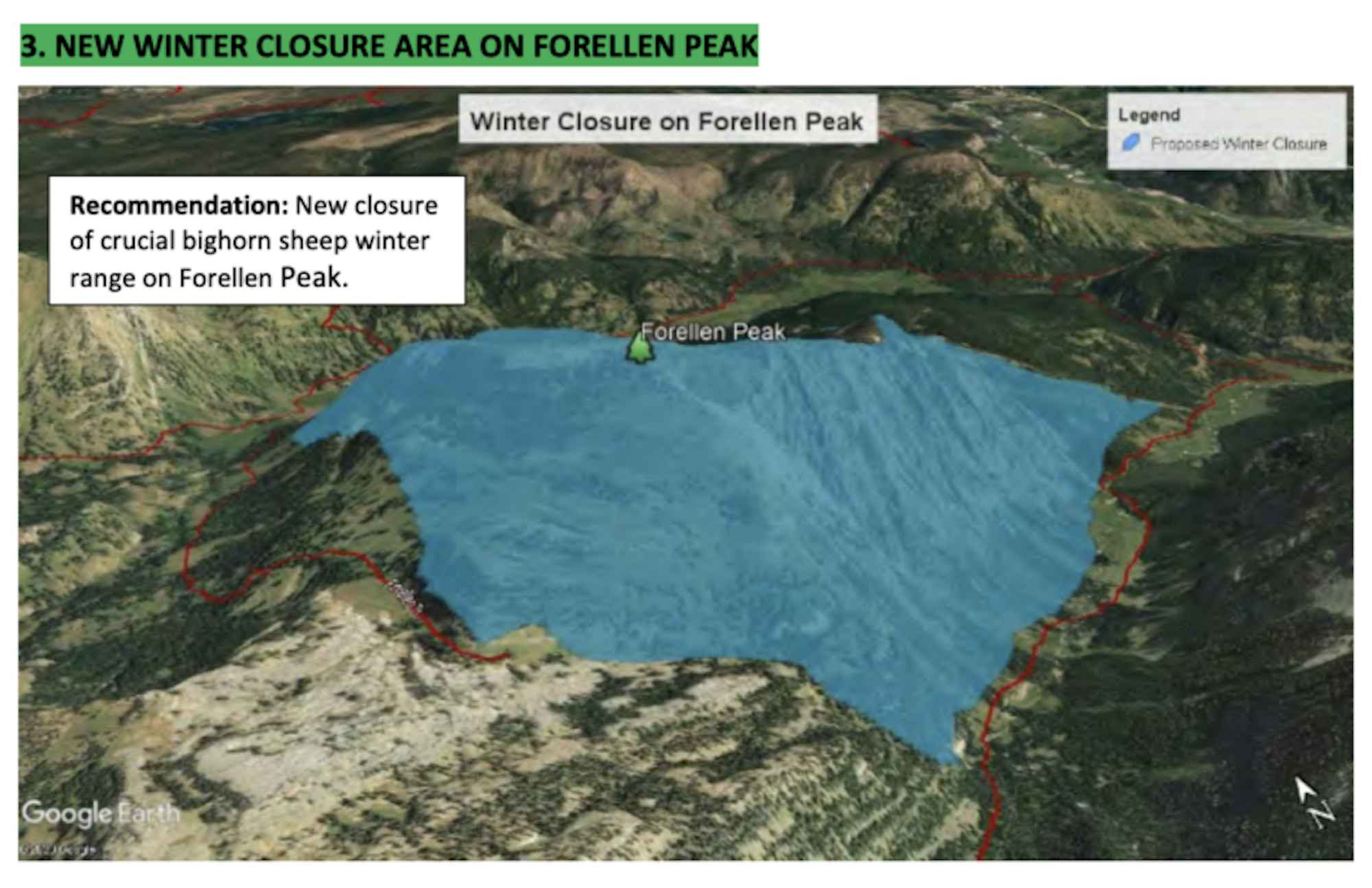

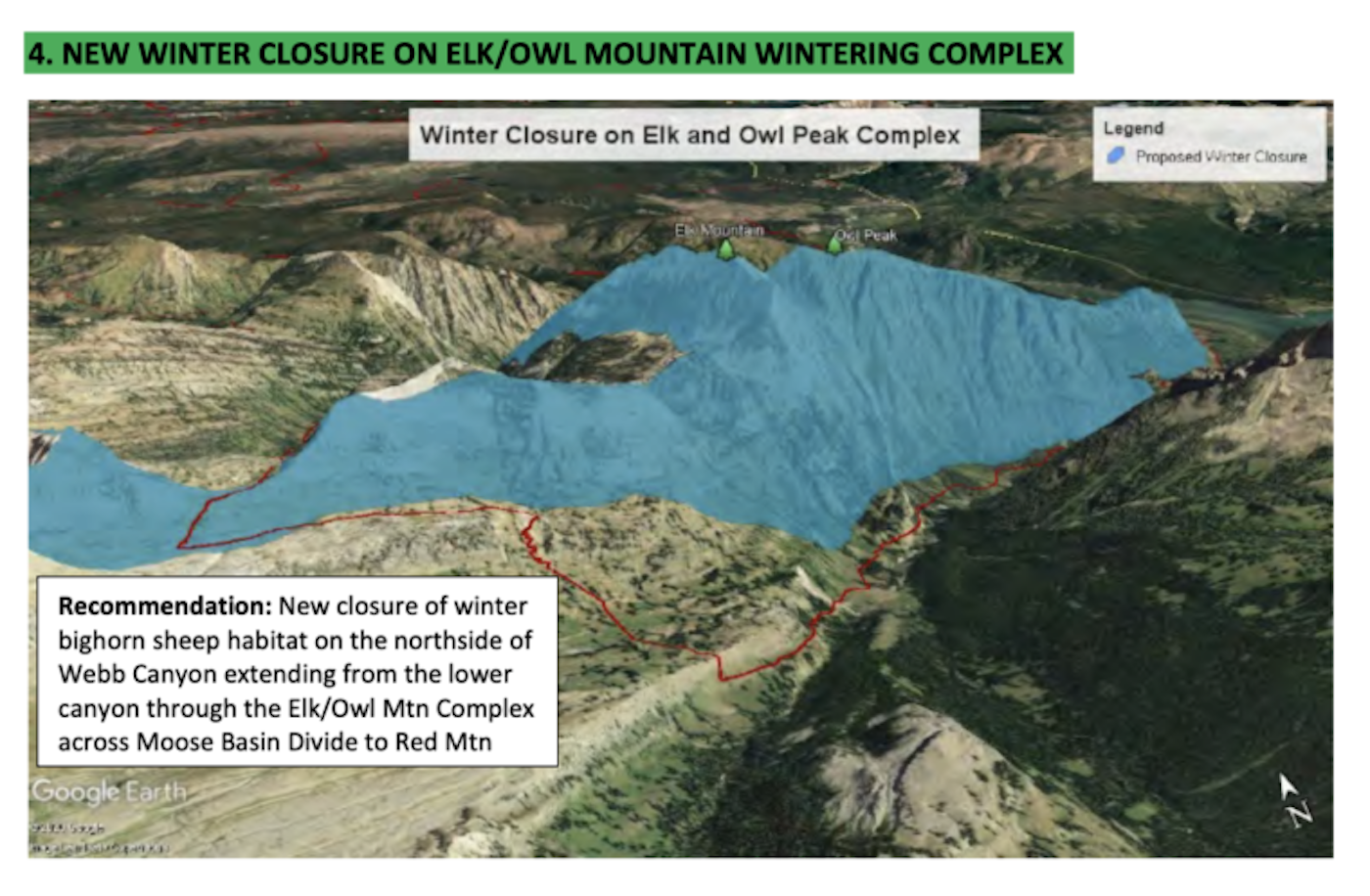

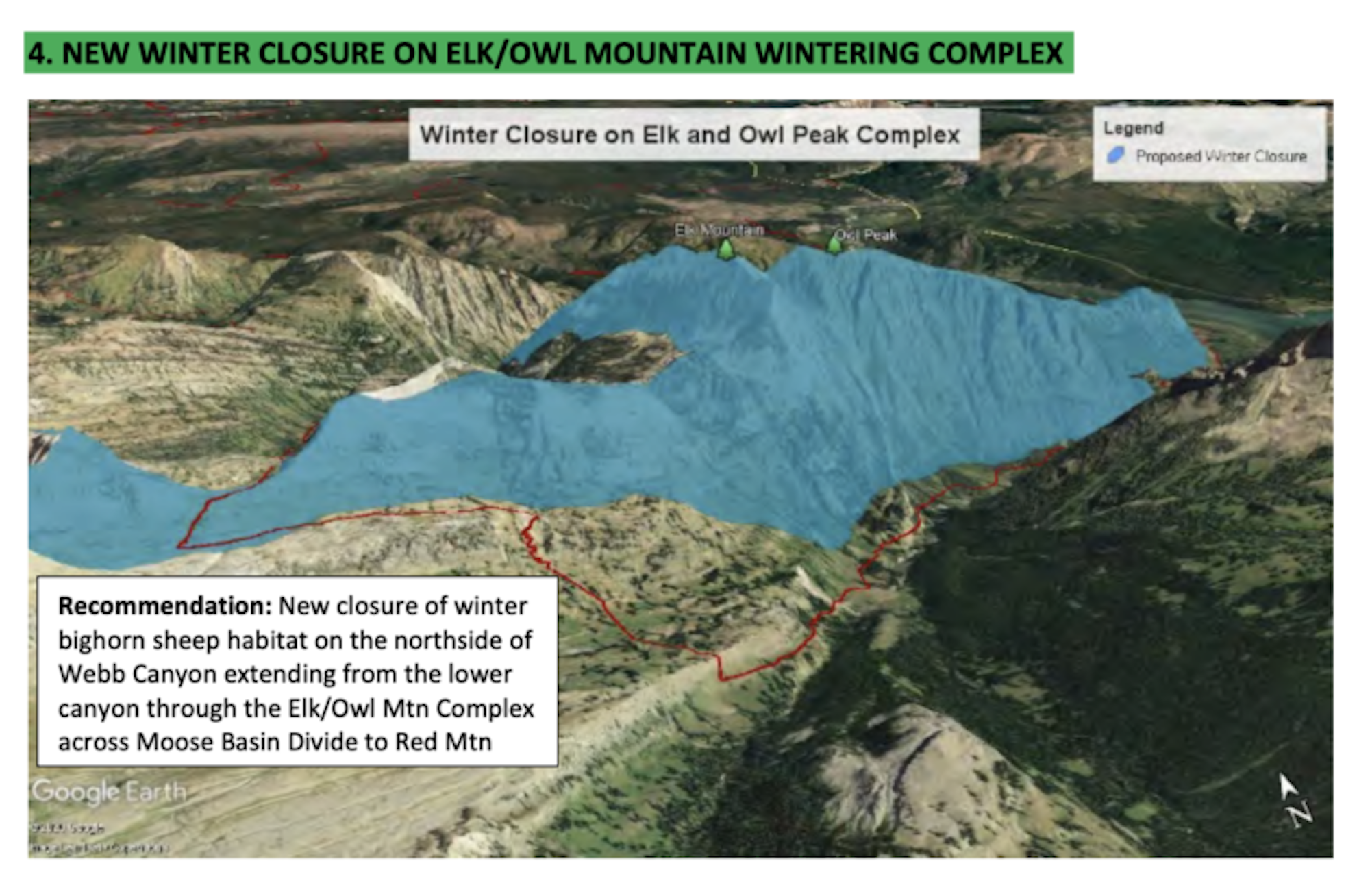

Examples of Proposed Closures:

While there is limited data that shows the direct impact of backcountry skiing on bighorn sheep populations, biologist Alyson Courtemanch published a comprehensive paper back in 2014 specifically on this topic. Her research shows that the existing closures, which have been in place since the 1990s, only protect around four percent of the 36,000 acres of high-elevation land that these sheep flock to every winter. The new proposed actions would effectively close half of that total area.

According to the Working Group’s document, the public identified 28,628 acres considered valuable for skiing. As a compromise, the proposed closures would only impede on nine percent of that skiable terrain—if all of the proposed actions were actually implemented. Areas like Granite Canyon, Garnet Canyon, Mt. Moran, Baldy Knoll, Taylor Mountain, Albright Peak, Wimpy’s Knob, 25 Short and the East Faces above Jackson Lake would all remain open during the winter months to prove the collaborative nature of the program.

Regardless, there’s been a mixed response from the public. On one side of the debate, the proposed actions seem misguided and arguably puts the local ski culture at risk. One the other side, many feel that the compromise of giving up some access is well worth it to protect the Tetons’ environment and wildlife from further human-caused damage.

Jeff Dobronyi, a Jackson-based IFMGA mountain guide, feels that the proposed actions are a disproportionate compromise and singles out the backcountry ski and snowboard community.

“The proposed closures represent a 15-times increase in the amount of closed terrain, and the biologists have mentioned that a two-times increase in the bighorn sheep population would be a successful conservation outcome,” Dobronyi expresses over email. “There are no recommendations to evaluate the closures for efficacy and repeal them if not effective, or to roll back the closures at a later date if the herd grows to a healthy size…We’d like to see a more proportional increase in closures, with specific recommendations to evaluate their efficacy. We’d also like to see a more modern approach to terrain closures, like closures that could shift year-to-year based on where the sheep are wintering and earlier dates for lifting the closures annually.”

Then there’s Hadley Hammer, a professional skier who was born and raised in Jackson. She’ll be the first to admit the magic of exploring deep and high in the Tetons but also observes the significance of maintaining the park’s native flora and fauna.

“In a world where 65-70 percent of wildlife populations have declined in the last fifty years, our bighorn sheep stir wonder and awe for their ability to persist in the Tetons for over 6,000 years,” she writes in an op-ed for WildSnow. “As the valley population looks to the park for backcountry skiing, many locals have pushed further and deeper into the canyons. This has benefits including finding new lines and solace from the crowds, but also exposes the skier/rider to higher risk and higher chances of disturbing the sheep.”

While Hammer understands the draw and significance of a backcountry experience in the Tetons, she also recognizes the inherent environmental impact of growing human activity in the wilderness and the rising need for legitimate compromise.

“It has been a privilege to access and ski the park,” Hammer continues, “but the sweet would turn sour if that privilege led to the extinction of a local animal population, even if it wasn’t the root cause.”

The recommendations outlined in the document developed by the Teton Range Bighorn Sheep Working Group are not official yet. An online meeting was hosted on October 20 of this year to provide a space for public comment and if you are interested in voicing your opinion, email or call the Working Group (alyson.courtemanch@wyo.gov), Grand Teton National Park, Bridger-Teton National Forest and/or Caribou-Targhee National Forest.

![[FIRST LOOK] New 2027 Skis and Outerwear From Rossignol](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1771280782-2026_fs-firstlook-deck.png?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)