AS RECOUNTED BY CODY TOWNSEND, WITH PHOTOS BY REUBEN KRABBE

“I had never considered the implications of engaging a mountain in a staring contest. Yet, there I was, a few hours deep into a stare-down with an Alaskan challenger. Its crown soared three-thousand feet above our village of tents, set up on its glacial foot. The beast peered down at me with its face of cleaved runnels and knife-edged spines. Two apartment building-sized chunks of ice balanced precariously on the peak like judging, gigantic, electric-blue eyes. I was waiting for the colossus to blink. To hesitate. To give me a sign… to reveal a secret. A hint at a route to the top. A path through the labyrinth of crevasses menacingly guarding its lower flanks. But, this mountain was not blinking.

Little did I know at the time, the stare-down would last nearly two weeks.”

— Cody Townsend

This article highlights an incredible winter camping mission deep in the Alaskan wilderness. Posting up in the rugged, heavily-glaciated Tordrillo Mountains, a crew including Cody Townsend, Mark Abma, Austin Ross and Zack Giffin camped beneath monolithic spine lines while shooting for MSP Films’ 2016 release, Ruin and Rose. After arriving in wild fashion—via prop-plane, packed to the brim with tents, ski gear, food, camera equipment and a keg for good measure—the group would spend two weeks together braving the elements and earning some of the best skiing runs of their lives. This was human-powered skiing at its finest.

The descriptions and tidbits that follow are the accounts of Cody Townsend, the Lake Tahoe skier known to the greater public as “That Guy Who Skied The Crack,” — with the “crack,” of course, referring to an absolute monster of a chute found elsewhere in the Tordrillos. The video clip of Townsend’s hair-raising descent has been viewed north of 10 million times. Yet, as you’ll come to find, a man of such YouTube fame is subject to the fears and realities of winter camping— just the same as everyone else. — The Editors

A total of five three-person, four-season tents slept our crew of nine while a pair of tee-pees provided gear storage and a sheltered kitchen. A thick, 12-man, double-walled ‘Arctic oven’ tent housed even more equipment and served as a daily gathering spot; here, we waited out storms, dried gear and read book, after book, after book. Typically, expedition-style winter camping affords nothing but the bare essentials. In our case, a bush plane-accessed drop on the glacier allowed us to bring a wood-powered stove, a generator to power electronics, three hundred pounds of food and a watering hole’s worth of booze. Sure, we were sleeping in the snow and a six-feet-in-thirty-six-hours storm buried our camp like a dog buries a bone, but ultimately, a little bit of heat and a great deal of nylon makes for accommodations as cozy as a three-star lodge.

Living communally in tight quarters and partnering up on daily, sometimes not-so-enjoyable chores in the backcountry can tax relationships. But, bring the right crew along and not only will the experience be more enjoyable, unbreakable bonds will form. Having the perennially-stoked but new-to-winter-camping Mark Abma; the young, but big-mountain experienced Austin Ross; and the most positive-minded, talented tiny-house-builder on the planet, Zach Giffin on the trip made for an outing that was nothing short of sublime. What began as a cordial friendship strengthened into a deep appreciation for, and innate understanding of one another, built on shared, intimate experience.

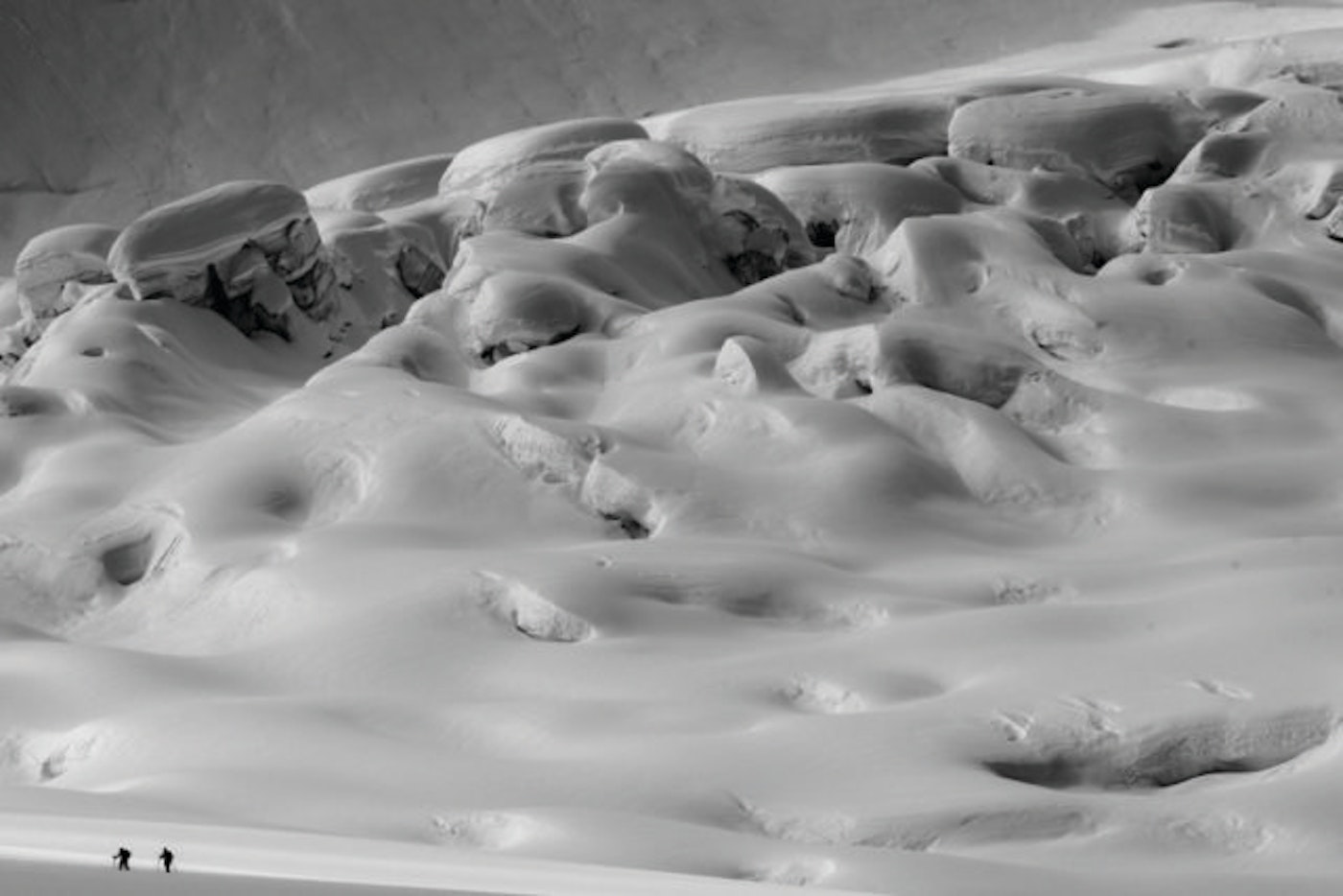

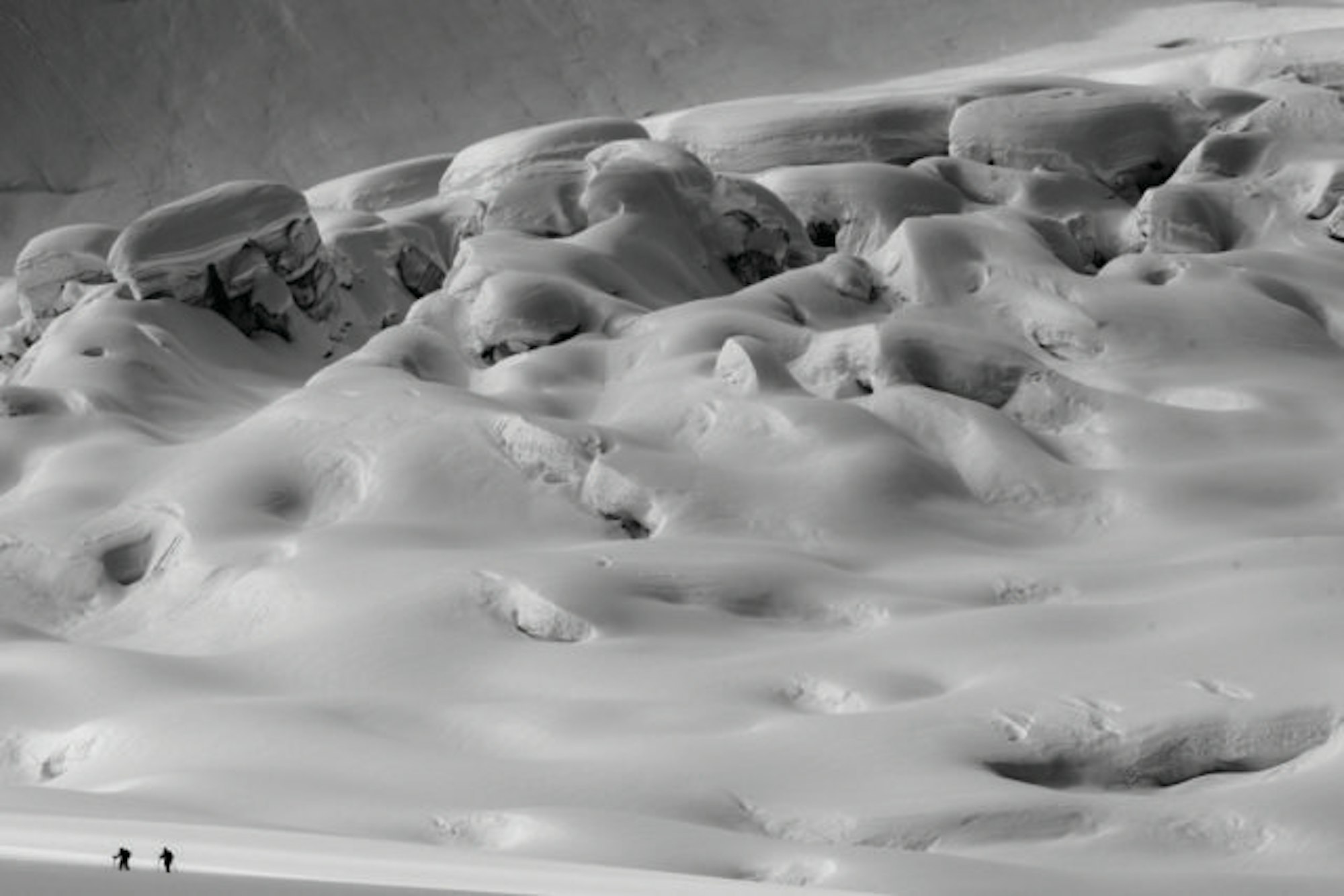

Powered by nothing more than our own two legs, moving slowly across the glacier and up the mountain was not just a tactic but also our only option. Yet, the glacial speed of movement became essential for recognizing the rhythms of the mountains and absorbing the information that the peaks distributed to us on a daily basis. During miles-long hikes across the glacier, we witnessed the diurnal snow settlement, sluff rolls in the shade and cornices that dropped after baking in the sun; these observations laid the groundwork for our decision making. Summiting a peak of Tordrillo distinction takes hours and you’re exposed to hazards all along the way; informed decision-making was critical when it came to getting safely back to camp.

Beyond sound decision making, proper equipment played an equally big role in keeping us safeguarded from the elements. “Dingle-dongle” steeze was an oft-judged component of our daily outings into the mountains. The more metal-on-metal jingles coming from your midsection—where ice screws, carabineers and rappel devices hung from our harnesses—the better. Looking like Jimmy Chin in Meru is fun, sure, but those little pieces of rope and metal are critical components of survival. A rope-less fall into a crevasse would most likely be fatal. The right knowledge combined with the right tools, though, might just turn a potentially deadly tumble into nothing more than a little scare and a big laugh. Rescue ain’t a 911 call away in the Tordrillos.

What’s more intimate than openly discussing the act of defecating? The classic book Everybody Poops does not lose its significance on a remote Alaskan glacier. So, although our camp was Blitzkrieged by a relentless blizzard, our coffee-induced morning movements did not suffer thanks to a hand-dug, 15-foot deep, fully-enclosed outhouse. There are few things worse than pulling your pants down in a gale force wind. A deep, snow-walled john tucked away from the elements prevented our steamer sessions from becoming the worst part of the day. It’s strange to think that the act of relieving oneself in such a setting came to feel normal.

Cold boots, having to get out of your tent to take a piss in your skivvies in a blizzard and sleeping a millimeter’s worth of nylon away from a terrifying onslaught of tiny ice crystals may seem strange and a bit scary at first. Yet, I’ve always noticed that on day four of a winter camping trip, the foreign and frightening suddenly feels quite regular. It seems to me that an internal shift occurs on that fourth morning; it is at this point that living in the snow and the loss of everyday conveniences is recognized and accepted as ordinary. It feels as though you revert from pampered human to the animalistic being that nature intended you to be. The one thing that perhaps never feels commonplace is the act of ascending a massive, intimidatingly beautiful mountain.

As your grand pappy will tell you, there are few things as rewarding as a job well done. Hiking and climbing for your ski lines gives you an endorphin- and adrenaline-laced experience that is nearly impossible to replicate. The first big line we tackled during this camping mission included a two thousand vertical-foot wade up waist-deep snow; traverses of a multitude of teetering snow-bridges; crossings of bottomless crevasses and bergschrunds; and a topping-out at a summit that provided a one-hundred mile view. The turtle pace with which we ascended was bookended by rabbit-like bouncing down pillow-caked spines, where blinding face shots came repeatedly. We roared all the way down to the glacial floor where a feeling of accomplishment led grown men to hug like school children. The quantity of runs a helicopter might provide in a similar setting was easily eclipsed by the quality of one, hard-fought, well-worked-for descent.

Remember the aforementioned, two-week-long stare down? Well, I eventually won. In a fleeting moment of submission, the mountain exposed the ultimate path to the grand prize above camp: the once-ridden, never-climbed, three thousand foot spine wall dubbed “The Wizard of Ah’s.” A two o’clock a.m. start time; a roped-up skinning mission in the dark of night through a maze of crevasses; and a thousand vertical-foot push up tits-deep spines was the key. As the sun cracked the horizon, Austin, Mark and I moved silently, nervously. And as the light of dawn revealed our position high above the valley floor, excitement, adrenaline and stoke fueled our final push. Stopping a safe distance below a city block-sized cornice guarding the summit, we latched our ice axes to our packs, clicked into our skis and stared down the ultimate reward. As the sun fully crested the horizon, I dropped in, letting my skis flow down the spine, edging and slashing the top of the ridge like a wave. Hooting and hollering spontaneously erupted from deep within me as I made my way down the face and safely onto the apron. The walk back to camp felt like returning to dry land following a hurricane-ravaged sailing mission. We hugged, shared our collective feelings of the descent and clicked beers together at nine o’clock a.m. because…. why not?

Mark Abma’s MSP athlete edit, largely filmed in the aforementioned Alaskan mountainsThis story originally appeared in the December 2016 issue of FREESKIER, Volume 19, Issue 3. Click here to subscribe and receive copies of FREESKIER Magazine delivered right to your doorstep.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Limited Edition FREESKIER Hat](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1772568976-3x4a9169.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)