NEARLY TWO DECADES AFTER RIKSGRÄNSEN WAS INKED INTO SKIING’S HISTORY BOOK, HENRIK HARLAUT WRITES A NEW CHAPTER

Words by Henrik Lampert with help from Daniel Rönnbäck

Photos and captions by Daniel Rönnbäck

In the spring of 1998, at Sweden’s Riksgränsen resort—the northernmost ski area in the world—a 20-year-old French-Canadian by the name of JP Auclair strapped on a pair of skis and launched 15 feet out of a hand-shaped quarterpipe. At the apex of his flight he reached down and grabbed his left ski just above the binding, then pulled hard, tweaking his frame into a form that was as strange as it was strikingly beautiful. Auclair then released the ski from his grasp, returned to an upright body position and touched down on the snow. Unbeknownst to him, he landed with a weight far greater than that imparted by the forces of gravity.

Such a demonstration of skiing style and amplitude was unprecedented. Immortalized in photographs, Auclair’s performance that day helped to launch a professional skiing career that spanned some 15 years. In that time, he earned enough awards and accolades to fill a book; he became a world-class skier, a family man, a star and director of ski films, a businessman, an entrepreneur, a philanthropist and, when he died in the fall of 2014, an icon of divine stature. Auclair’s showing at Riksgränsen was a defining moment in a sport that was on the verge of a progressive boom, a movement marked by big air and highly technical tricks. By extension, the area became a sacred landmark of sorts—the place where JP Auclair set in motion a domino effect that changed skiing forever.

Eighteen years later, in May of 2016, a byproduct of Auclair’s influence trudges through slushy springtime snow in the backcountry outside of Riksgränsen. The 25-year-old Swede idolized Auclair both as a child and now as a young adult. He’s sponsored by and represents the company Auclair co-founded in 2002—Armada Skis. And, like Auclair, this individual is an innovator of skiing; the Olympian, three-time X Games gold medalist, two-time recipient of FREESKIER’s Skier of the Year award and star of Inspired Media films skis with a style so unique it has earned him a full-fledged cult following. Trekking into the remote, beautiful wilderness on hallowed grounds in the Arctic Circle, Henrik Harlaut is here to pioneer new forms of skiing. He follows a path laid before him nearly two decades prior. But somewhere along the way, he diverges, intent to blaze a trail all his own.

—

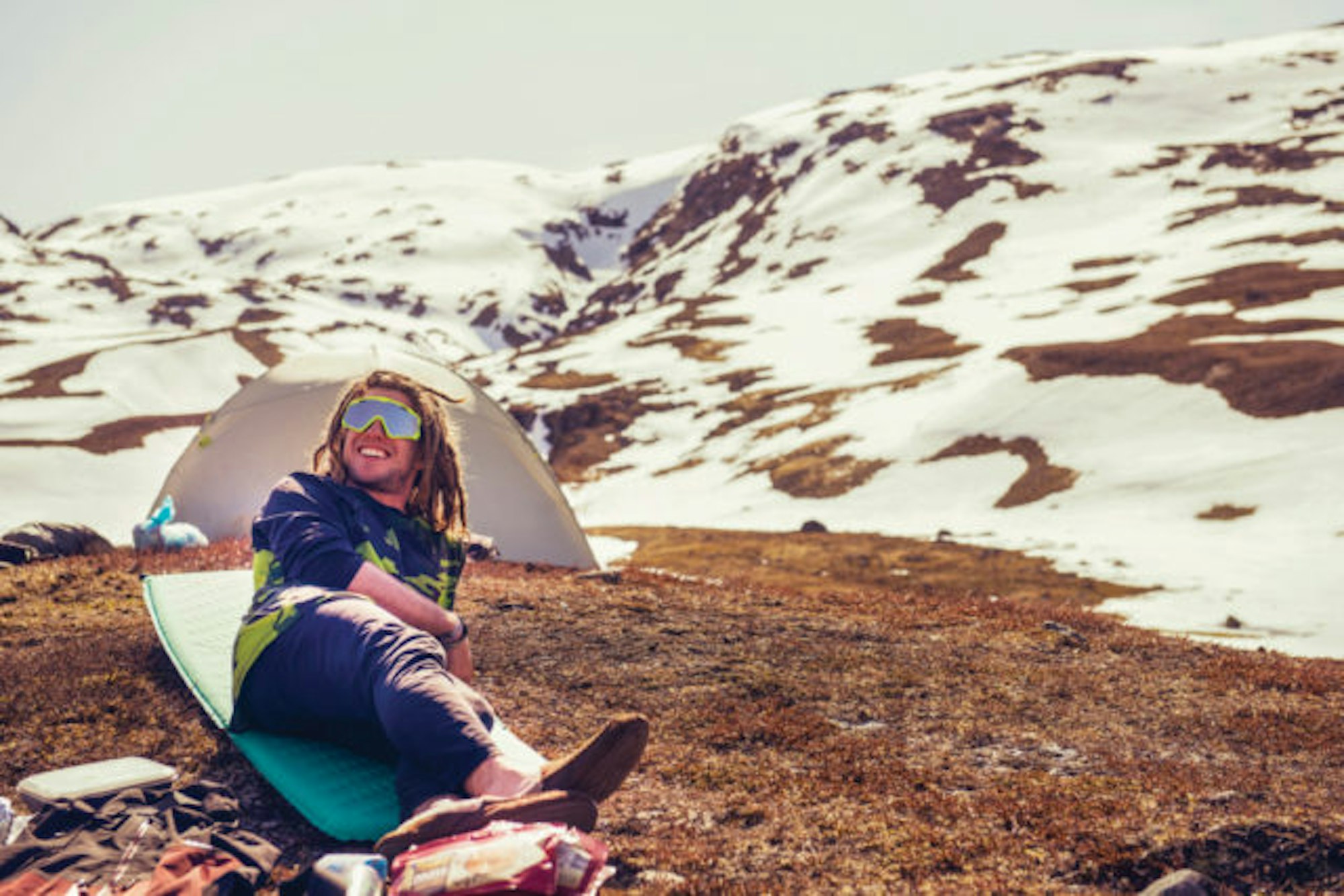

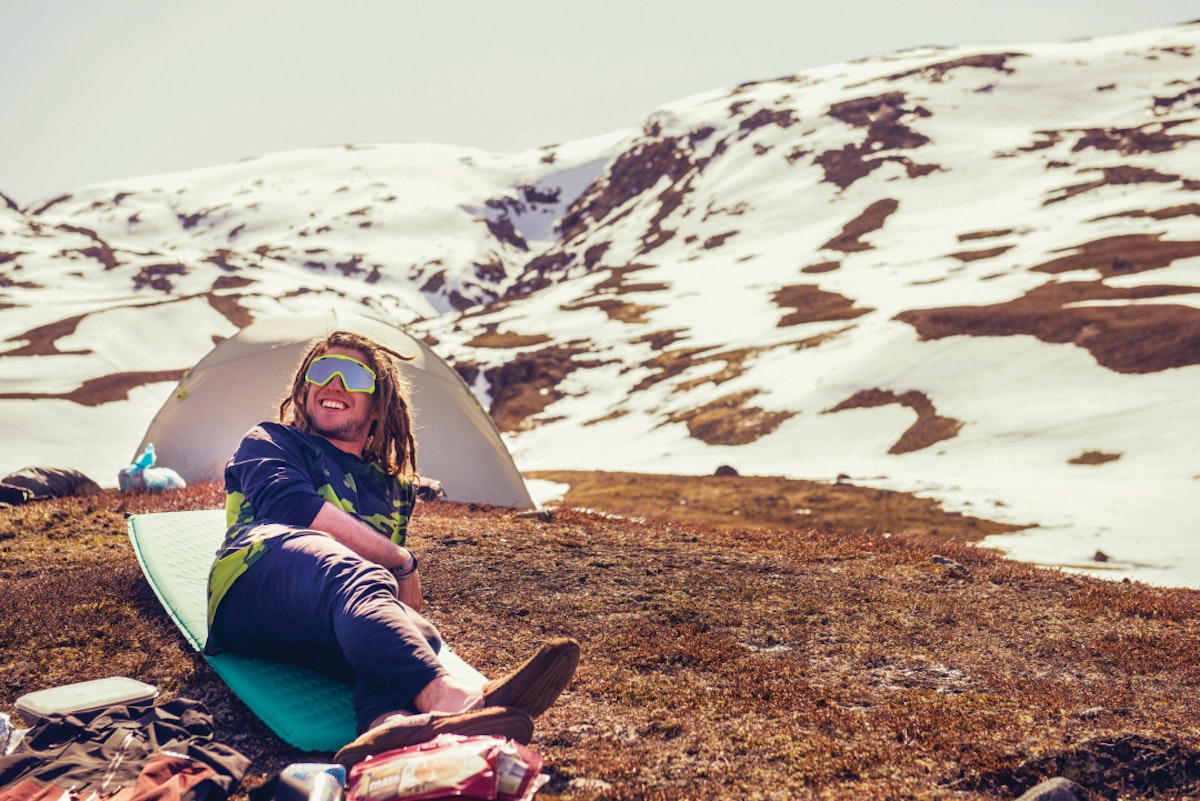

Three-layer Gore-Tex. Featherweight skis, boots and bindings. Dehydrated food. The lightest spork on the market… These are things that you may associate with a ski-tour-accessed backcountry camping mission. Full-Tilt B&E LTD terrain park-centric ski boots. Cotton sweatshirts. Saggy ski pants held in place by shoelace suspenders. A twin mattress and a down comforter pulled on a toboggan. Fifteen pounds of Monster Energy drinks. Plus, beer, candy, tins of snus and heavy, canned food items… These are things you may not associate with a ski-tour-accessed backcountry camping mission. But they’re he things that Henrik Harlaut and his Swedish cohorts carried with them on a three-hour tour into the Riksgränsen backcountry. Odd as it may be to substitute a mattress for a sleeping pad and a blanket for a sleeping bag, these skiers are unorthodox more than they are irresponsible. Beacons, shovels, probes? Check. Suitable all-weather tents? Check. A mindset to ski-tour, hike, explore, build jumps and generally enjoy the great outdoors? Check. One thing can’t be denied: This motley crew enjoyed a camping trip of the fun-filled, free-spirited sort that people fantasize about—spring snow, midnight sun, warm temperatures and all.

The name “Harlaut” tends to elicit thoughts of big air contests and street-skiing, but Harlaut himself admits, “If I only skied park, then I could see myself getting tired of it. “Going into the backcountry, he says,keeps everything in balance. “Switching things up, skiing in the park, in the streets, in the backcountry, it opens up endless possibilities. There’s no way I could ever get tired of that.”

With a mind for learning new tricks in a non-park setting and documenting the experience for Inspired Media’s 2016 release, BE Inspired—a film starring Harlaut and Phil Casabon—Harlaut shows off a side of his skiing not often seen. In so doing, the Swede brings light to the idea that outside of the essential safety tools and a respect for the inherent dangers of traveling out of bounds, top-of-the-line gear is not necessarily required to enjoy world-class backcountry skiing. This sport is for everyone.

Why is Riksgränsen so amazing?

Riksgränsen is so amazing because you really can ski whenever you want—the sun barely ever sets [depending on the season]. And when it does set, it only just dips below the horizon and it’s still bright outside. Also, the terrain is unbelievable. There are so many rollers and fun things to build jumps off of. I find it’s the place where I’m most productive in terms of shooting film and photos. Elsewhere in Sweden—Åre, for example—it’s super, super nice, but it’s easy to get caught up with the party scene or just skiing in the terrain parks. A place like Riksgränsen is the perfect spot to get away. There is nothing else to do here besides ski.

Talk more about that—escaping distractions and just focusing on the skiing.

It’s the most awesome place for skiing and I’m the biggest skiing fan, so it’s perfect. There are no distractions at all. It’s just friendship and skiing, and that’s all that matters. It’s a dream.

What sort of headspace are you in when you’re away from civilization?

[Off the grid], you can really meditate and think about the things you want to change and make better in your life. When I’m out there, I always think about and give so much thanks for the friendships I have, and I appreciate how much all of my friends care for me. One of the best times for me to get into a nice mental state is while skinning. It’s almost a spiritual mindset.

Being out here and touring, it opens our minds to what we really need and makes us think differently about what we have. We also think differently about what we can do with what we have. This trip really reflects that. Our crew didn’t have the perfect gear but everyone did the best with what they had. I hope more people will come to appreciate what they do have and just get out there and enjoy the mountains. — Rönnbäck

Do you think about JP when you’re skiing at Riksgränsen?

Definitely. Growing up, [Riksgränsen] was such a unique and big place for Swedish skiers. Seeing the photos of JP and JF [Cusson], and also Jon [Olsson] and Henrik [Windstedt], I knew there was something special about the place. I remember I was always so excited to go there and I wondered when I would finally have the chance. So, 2014 was my first time up there and it was just like what I envisioned in my dreams. It was awesome.

As someone who rose to fame primarily for his terrain park prowess, can you touch on your first foray into the backcountry?

When I was younger, I was always looking at things as either big-mountain or park. Being able to enjoy both never occurred to me. At that point, I didn’t really like the big-mountain scene much because it was a bit too slow for a little 10-year-old hyperactive kid. The park was more intense and more, bam, bam, bam. I like that. Tanner [Hall] is the main reason I got hyped on backcountry. He was mixing park and backcountry and I would rewind and watch his video segments over and over again. Eventually it was CR [Johnson], Candide [Thovex], everybody… they all started [incorporating] tricks into their lines and building jumps away from the resorts. When I discovered it myself, I experienced the feeling of being so nervous before my first hit. Then, being able to stick something on the first try and riding away and seeing just one perfect set of ski tracks going down a landing… it’s such an indescribable feeling. It was so amazing.

Talk about the process of building jumps and learning tricks in the backcountry compared to learning tricks in the park.

Well, while building the jump you really have the time to think about what sorts of tricks you want to throw. I really like that. I am always thinking about new things to do, whether it’s tricks, edits, contest formats, styles of jumps… It’s also a lot harder to land new tricks in the backcountry. So, when I go to the park after learning a trick on [variable] snow conditions, it’s so easy.

Trekking into the backcountry and hand-shoveling jumps can be tiring. How do you maintain the energy to jump?

Every time I’m out [in the backcountry], I’m thinking about the next mission and I hope to be in even better shape, have better cardio… so it’s even easier to hike out there and build jumps and maintain energy for the [jump] session. But, it’s definitely hard sometimes, especially if you don’t land your tricks right away. It’s the best if you have a three-jump session and you land your tricks and you’re done and you’re stoked. This year I had a few tricks that I really wanted to do that I couldn’t land and it was so, so hard ‘cause I had to hike the jump maybe eight or nine times more than I wanted to. That was definitely pretty draining. But, like I said, hopefully the next time you get out there you’re a bit stronger and in better shape so it’s all easier.

How can backcountry skiing become more accessible to people who haven’t ventured out of bounds before?

I feel like it has grown a lot already. For example, being up in Riksgränsen in 2014, we were basically the only [park-centric] skiers up there camping and building jumps. It was really just us out there. Two years later it was like, 10 to 15 crews. I feel that people are starting to see how awesome it is and they’re starting to explore and I think it’s only going to get bigger. Just those two years… it’s crazy to see how fast it has grown. With the gear getting better and more technical every year it’s only getting easier for people to accomplish this. I imagine in five years we’re going to see so many more people out there. Even if you don’t go to build jumps… you just go to skin up the mountain and have an awesome ride down… just making some pow slashes and whatnot, you’re going to experience that and know what pure happiness is. People just need to go, have one experience and build from that.

It’s rare that Henrik has the opportunity to ski and hang out with his childhood friends. These were the same friends he shared his first camping experiences with as a young kid. They’re super good skiers who just don’t have the sponsors and possibilities to travel as much as Henrik. Still, they ski almost every day. To see them all together blasting music from the boombox they brought out on the mountain, skiing and hanging together above the Arctic Circle, in the wilderness behind the northernmost ski resort in the world… It was very special. — Rönnbäck

What about people who don’t have proper backcountry gear… is equipment a barrier for people getting into this aspect of the sport, in your mind?

I mean, if you want to skin, you need skins and touring bindings. And you need the obvious… the beacon, shovel and probe. I wouldn’t want to go out in the backcountry without everyone in my crew having those essential [tools] and knowing about their use and function. But, you don’t need all the other gear— at least depending on your location. In a place like Riksgränsen, I use my park gear. It’s how I feel the most comfortable. It’s not the best material for being out [in the backcountry], but, I like it.

What about boots?

I use normal park boots. I love them. They’re the best boots for my feet, so I don’t want to change anything about that.

Even on a three-hour tour?

If you ask me, yeah. [Laughs] Obviously, the lightest and most technical gear is amazing. But, you don’t need it.

I’m the only one that had actual touring boots and frameless bindings. Everyone else used alpine boots and binding options like the [Salomon] Guardian or [Marker] Tour F10. Henrik had his bindings mounted to his park skis and it worked just fine. He has the motivation to go up and tour and hike and build and land those tricks, and that’s the cool part. He is so motivated to work for what he wants. — Rönnbäck

What kind of food did you bring with you?

I try usually to pack as light as possible, but my bag always ends up being so heavy. I try to bring something quick and easy but also something that still has enough nutrition to keep me going strong the next day. Oatmeal with bananas and cinnamon is a big one for me.

What about the Monster Energy you brought? Those cans weight a lot.

Yeah, it’s not so light on the way out to camp. [Laughs] But the Monster… I need the energy. The energy is key.

We were out there six or seven nights. We toured everyday and had 20 hours of light. It was always better to go ski in the afternoon when the snow was softer. The light was better at that time, too. We just chilled and hung out during the day. The group laid in the grass, enjoyed the sun, ate food, listened to music. At dinner time, we’d go up and session until midnight or so. Then we’d go down to camp, enjoy the sunset and hang out until 2 a.m. before we went to bed. It was a good life. — Rönnbäck

Do you have a message for people who might be scared to venture into the backcountry because of the inherent risks?

There is a lot of learning. I’m like, not even close to being well-experienced out in the backcountry. There’s so much to account for with snow conditions, temperatures and terrain… I don’t think you can ever really be an expert when it comes to being safe out there. You can have all the facts, but some things will be out of your control. It’s endless learning. Safety is my biggest concern while being out in the backcountry.

Note: This article appears in FREESKIER magazine Volume 19.3, the Backcountry Issue. Subscribe to FREESKIER magazine right here.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Legendary Ski Trip with Icelantic's Road to the Rocks](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765233064-r2r26_freeskier_leaderboard1.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Head-to-Toe Ski Setup from IFSA](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765920344-ifsa.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Legendary Ski Trip with Icelantic's Road to the Rocks](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765233064-r2r26_freeskier_leaderboard1.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Head-to-Toe Ski Setup from IFSA](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765920344-ifsa.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)