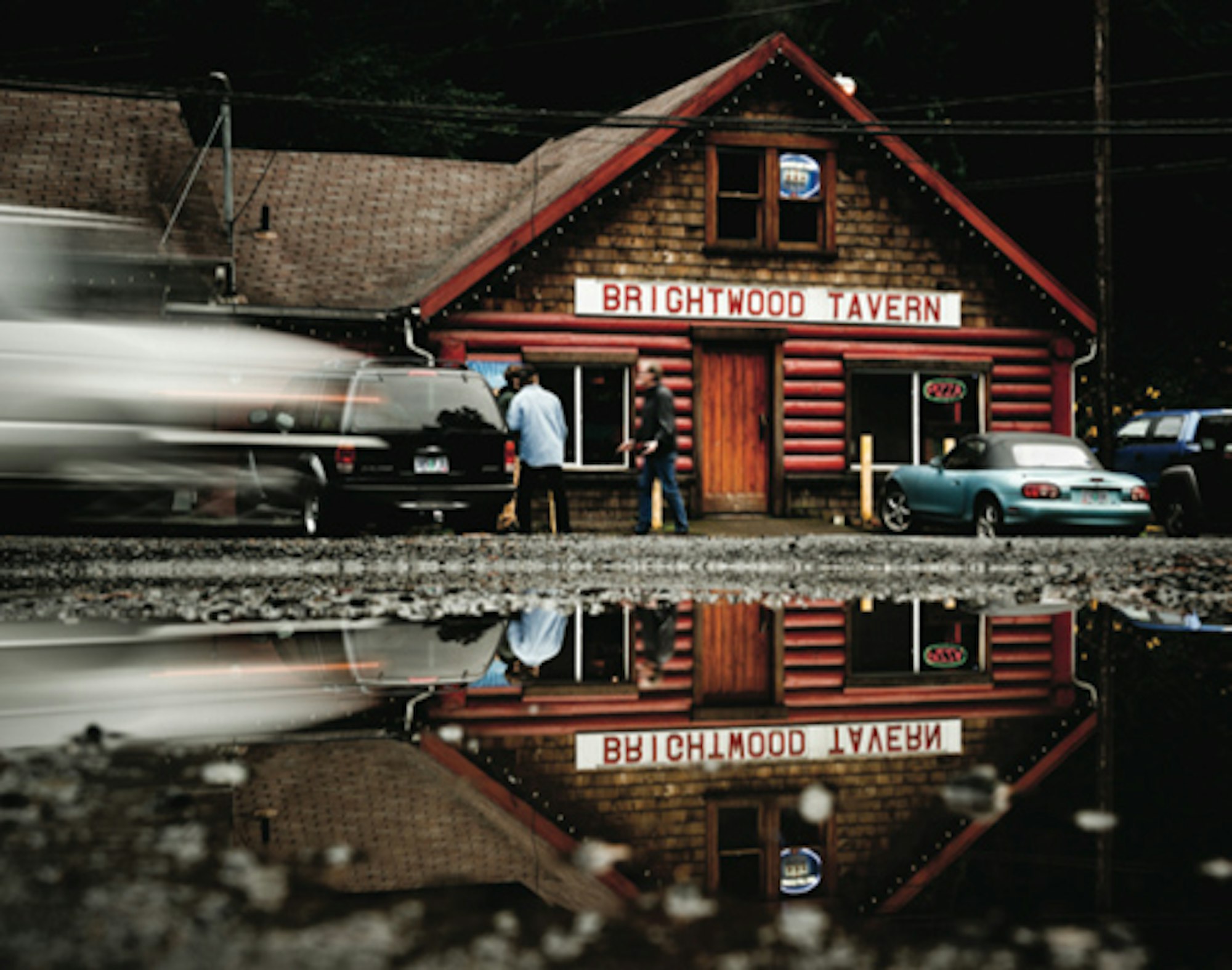

Our eight feet crunched on the sandy pavement where the road became parking lot. We walked through the red front door. Inside, it was dark and the air was stale with the dusty smell of time. The Brightwood Tavern was still there—a shanty built a hundred years ago by someone with a yen for log cabins. In the time since, the building had been added on to with extreme bias, like a trailer home with many bastard additions.

The place was empty except for two cowboys by the jukebox. We sat at the bar and ordered Caucasians. This might seem odd to someone who has never cultivated a proper taste for dairy mixed with booze, like the acne-faced German girl I’d run across in Government Camp the day before. “White Russians are for gay guys,” she whispered loudly in my friend’s ear while I was speaking on the finer points of the beverage.

“You’re a nihilist,” I said. But she didn’t understand. There was much she didn’t understand.

So I felt a certain obligation to have a Caucasian when Big Bennard ordered one, heightened by a sense that the Brightwood Tavern was the kind of place where we could drink without explaining ourselves to German girls.

But any illusions of peace were broken when I felt the tap on my shoulder…

In spite of its seclusion, or maybe because of it, the little town of Brightwood has more than a few crazies. We’d recently made friends with a toothless Portuguese Indian named Jesús from around the way, a noble savage with a reputation for quoting Descartes and welshing on his gambling debts.

There was a rush of blood to my brain as I turned around on the barstool. The man facing me was one of the cowboys from the way in. He was wearing a Canadian tuxedo. At a glance, he could have been 47—or 63.

“You look jest like George Thorogood,” he said to me. “Shit, man, I know George and you look jest like him.” I’ve never counted Thorogood among the gods of rock-and-roll, but I decided to keep that to myself. It was high praise.

“You guys snowboarders?” he asked. He’d seen our type running around Mt. Hood many a summer.

“Fuck no, we’re skiers,” Parker White answered before I could say anything.

The cowboy jumped backwards in shock. I thought for a second that he must have had a deep-seated hatred for skiers that was about to manifest itself in an Old West style of justice. Instead he grinned big and hooted, “Yee-ew!” The years showed in the leathery creases of his smile. “Slat rats! You hear that Curly? We got us some slat rats over here.”

Curly was still fucking around with the jukebox. “Naww, ginuwine?” he said.

“Yep,” said the first cowboy, “we were skiers too, a ways back. Stick dodgers, slat rats! We shore use to raise hell.” He craned his neck to look at the patio outside. “If my old lady wun’t here, I’d give ya the real dirt.”

He winked and stuck out his hand. “They call me the Slug Queen,” he paused for effect, “which means I get laid, a lot.” It was hard to tell how his old lady figured in to all that. Curly made a face like he was tired of the Slug Queen’s politics.

I could picture the two of them 35 years back, skylarking around Government Camp with a bevy of bell-bottomed babes, kicking ski-boot holes in the walls at Charlie’s and the Ratskellar.

We never did figure out exactly what a “Slug Queen” was or why he was so proud to be “the first male Slug Queen in history.” The Queen tried explaining something about an annual slug race, but none of it made any sense. He was probably just drunk on some old-fashioned feeling. Maybe just drunk. Every so often, he’d point to an unlabeled bottle behind the bar and tell the big-boned barmaid, “Shot,” like a character from a Sergio Leone spaghetti western.

“She’s my daughter,” he explained after the third or fourth shot, “so don’t git no ideas.” His whiskey wit had come to ferment. The drink seemed to have the opposite effect on Curly, who was very tall and serious. When he talked about skiing, he got serious as hell.

“We had cable bindings,” he said, carefully, as if testing his handle on a forgotten language. “You had to break your leg to git ’em off. Still got pins in mine. I don’t git up there much anymore. It just ain’t the same.”

Curly didn’t elaborate on how skiing had changed. I guess he figured that we could see for ourselves, or that we would soon enough if we hadn’t already. After Curly spoke his piece, he dragged the Queen back over to the jukebox and played “Bad to the Bone” followed by “I Drink Alone.”

I felt a sense of relief as they left us to our drinks. We’d been tested; there was no doubt about that. And we’d made the grade, but I worried that we might not bear up under a more intense kind of scrutiny. It was a needless feeling.

“Slat rats,” Curly said as we got up to go. “It’s a state of mind.”

“Bring it back,” the Slug Queen added.

“Don’t worry about that,” Parker said, “We’ve got friends.” They nodded and tipped their Stetsons at us before the heavy wood door swung shut behind us. There was much they understood.

We walked back to the house along the road. The lights and trash-barrel fires of Brightwood strobed through the foliage below. The creatures of the woods were partying down there in the damp August night. Even in the dark, the salmon made their run up the Sandy River. The fish were returning to the spawning grounds of their birth.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Limited Edition FREESKIER Hat](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1772568976-3x4a9169.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Limited Edition FREESKIER Hat](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1772568976-3x4a9169.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)