[juicebox gallery_id=”172″]

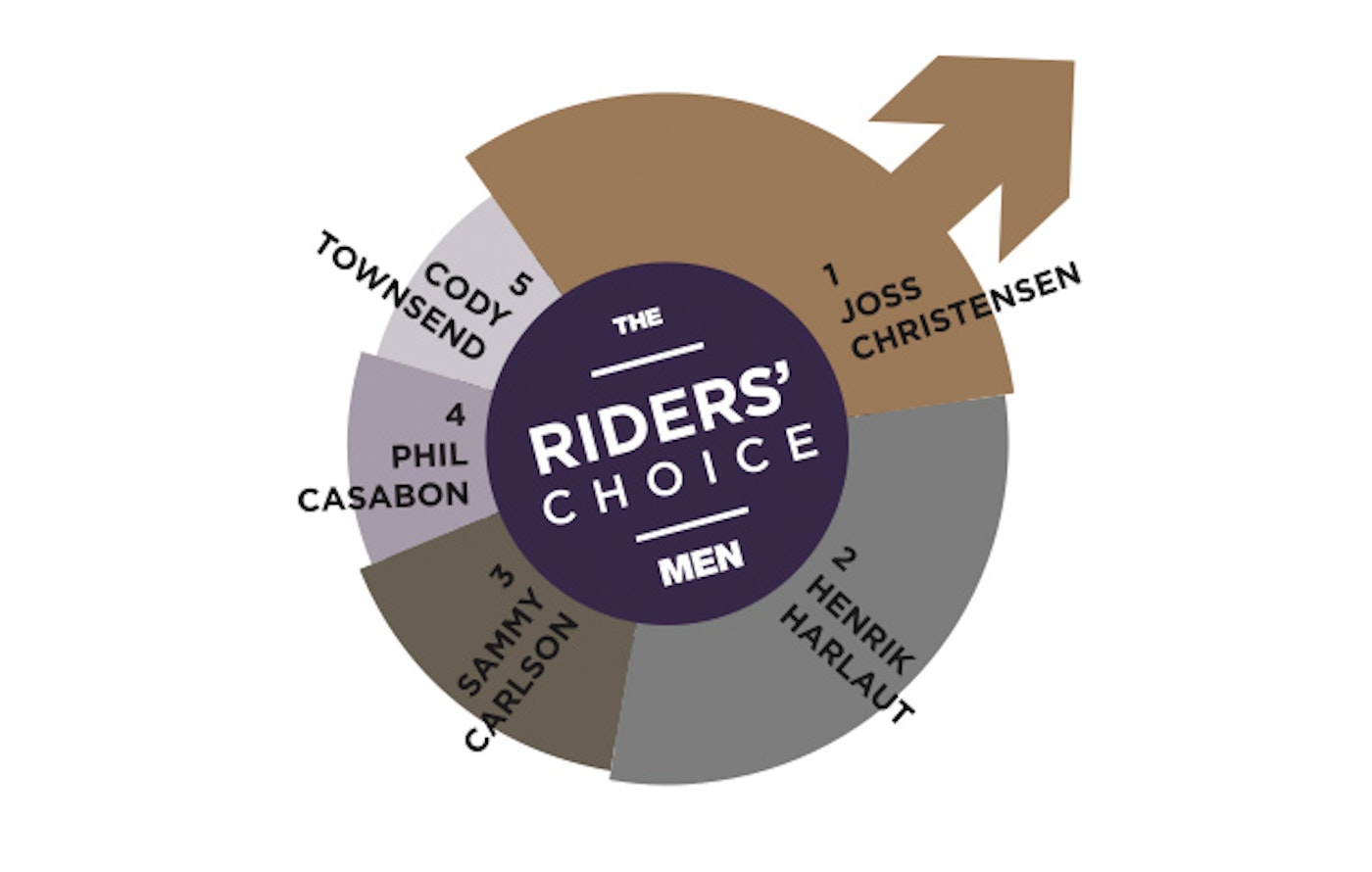

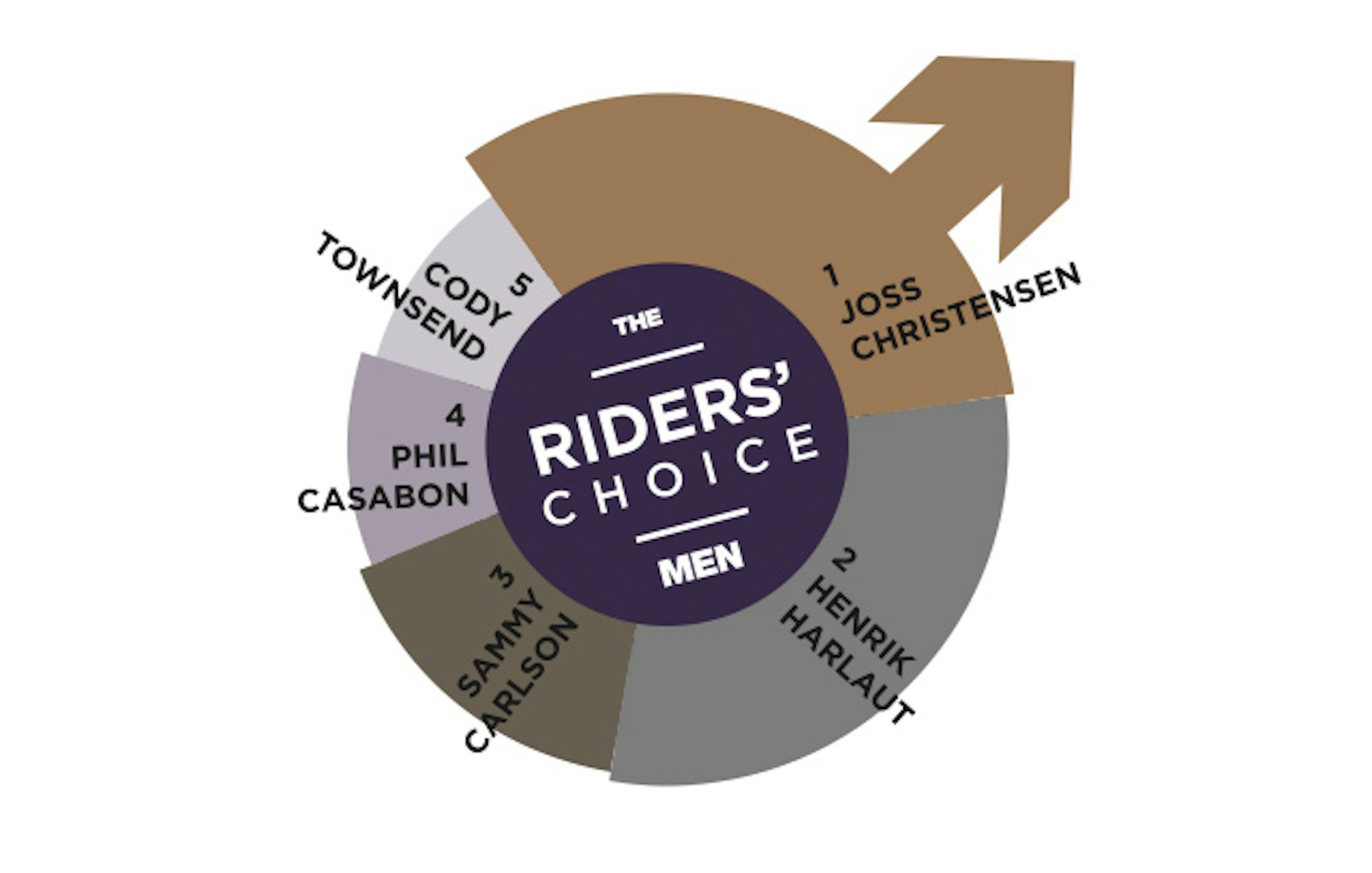

Joss Christensen is your 2014 Skier of the Year — Riders’ Choice award winner

How it worked: We called upon the sport’s biggest names and asked them to rank the 10 skiers they felt had the best 2013-14 season. We left the definition of “best season” open to interpretation but asked the pros to consider all factors from film parts, to contest results, online edits and overall impact. More than 100 top-name pros cast their votes, securing this award as one of the greatest distinctions in skiing.

Announcement: The 2014 Skier of the Year winners are…

It’s one of the most well-known musical themes in TV history. It begins with a booming and stately kettledrum soon joined by that distinctive bold trumpeting. The iconic Bugler’s Dream snaps us to frothing Olympic attention, usually followed by a familiar broadcaster’s voice leading directly into a heartwarming story or pulse-pounding competition showing how an Olympic champion is made.

It’s irresistible. The road to winning Olympic gold is retold every two years. Skiers and the general public alike schedule life around bearing witness to this pinnacle of athletic achievement. In fact, 242 million people in the USA alone tuned in to last winter’s go-round in Sochi, Russia. The ratings tell us that a total of 26 million people watched Joss Christensen win a gold medal in slopestyle’s big debut.

Christensen and the 2014 SOTY trophy, crafted by Mark One Metal Works, Carson City, NV.

“It’s like the ring,” Christensen nervously says, referring to J.R.R. Tolkien’s Hobbit ring of malevolent power. “It was like I was given super powers with the medal. But it’s weird too. All of a sudden I had thousands of random fans on social media. People would walk up and just grab [the medal], like, ‘Let me see it.’” The 22-year-old Park City, UT, native tells me this over the phone from his room at the Village Hotel in Breckenridge, CO. It’s almost Thanksgiving 2014. Training season. And Joss is in good spirits. As always, he is humble and polite to a fault but genuinely excited to talk about the half acre of land he just bought above Park City, a new snowmobile plus a truck to haul it. “I have everything I need,” he says, and I can hear him smiling through the phone.

Rewind one year to this same hotel. The prospect of qualifying for the Olympics had the entire lot of competitive freeskiers more focused and stressed than ever before. It was a brutal time for the athletes who were working to garner points and podiums in hopes of meeting the qualifying criteria. Joss’ roommates, Alex Schlopy and Sammy Carlson, also Olympic hopefuls, had decided to go back to their families for the holiday. Joss opted to stay and ski. While it was a rough time for many athletes—battling injuries, each other and the somewhat cryptic qualifying rules—Joss was dealing with much more; he was in the middle of mourning the death of his father.

He sat in a quiet hotel room on Thanksgiving, alone. Unsure of himself, the fun sucked out of the sport he loved more than anything, he doubted if he even wanted to ski anymore.

The months after JD Christensen’s passing, in the late summer of 2013, seemed to bring one body blow after another. Joss’ mother Debbie, who was understandably devastated by the loss of JD, needed assistance with odds and ends. They had to sell JD’s truck, motorcycle and other equipment in order to help keep the family afloat. And if that wasn’t enough, in the midst of it all, Joss and his long-time girlfriend went through a harsh breakup. It was the darkest time in his life. “I thought, well, it’s just survival mode now.”

In that deep hole of loss, Joss didn’t want to go home and do the turkey-holiday thing. He told himself to stay—train.

He sat in a quiet hotel room on Thanksgiving, alone. Unsure of himself, the fun sucked out of the sport he loved more than anything, he doubted if he even wanted to ski anymore. He questioned his determination to achieve a goal that seemed distant and unattainable. Especially for a skier, who in his entire career, had never won a major tour event. Joss’ father died at 67. It had been a lifelong battle with his heart, and the family was well aware of the condition. The raised scars of multiple open-heart surgeries running the length and width of his chest told the whole tale. Joss spent much of the summer in 2013 at his father’s bedside, along with his mother and brother. This was the most important time in his career, and it was a constant emotional pendulum. He struggled to balance skiing with being present for his family and his father.

Later in the summer, Joss rushed home from a training camp in Whistler to see JD after a critical surgery. There was hope, but the family was on watch. “We were at the hospital every day,” says Joss. In early September, he faced an agonizing decision: compete in a World Cup event in New Zealand, one of the last chances to gain points to qualify for Sochi and pursue the Olympic dream, or stay with his family. At that point, his father could no longer talk, but Joss knew, deep down, what JD wanted. He spent that day at the hospital with his mom. “The doctors were telling me it could be any day. I still didn’t really want to go [to New Zealand], but I thought I had to push for the Olympics. My father had been such a big supporter. He would brag about me. I know he would never have wanted me to let him hold me back from skiing. That’s how much he loved me.”

Joss shared his last moments with his dad and said what he needed to say. Then he got on an impossibly long flight to New Zealand. He learned upon landing that JD had passed away. “They let him go that night,” he explains.

Watch: Joss Christensen’s Olympic gold-medal-winning run.

But it wasn’t over. Now, he had to make a decision about whether to stay and compete or get back on a plane. He chose, with the support of his manager, mother and the US Team, to go back home. He couldn’t get out of the country for three days. So he hit the slopes with his good friend, McRae Williams. “We skied for two hours in the fog. I took two laps. It was such an eerie day. You couldn’t see anything. It was so quiet and foggy. It was claustrophobic. I felt like my dad was there,” he recalls, guiding him through the fog.

When he returned home, he walked into a quiet, empty house. The routine of going to the hospital was over. Joss had retreated to his family. He needed to breathe. Having bailed on the World Cup and the Olympics being the furthest thing from his mind, his future was uncertain. But once the snow fell in Colorado, he went back to training. This is how he found himself at the Village Hotel, alone on that Thanksgiving night, asking himself, “Is this for me?”

By his own admission, this led to an “oversized attitude” at a young age.

Joss was born December 20, 1991. “He was premature. Five to six weeks early,” his mother, Debbie, explains. “His lungs weren’t developed. He weighed six pounds, five ounces. Very determined. A fighter in that way. But he was always shy. He really expressed himself with his skiing from the beginning.”

At 3 years old, Joss would get dropped off at Deer Valley Resort for ski school, while mom and dad ripped around Park City. Joss followed his older brother Charlie on and off the hill. For years it continued. He loved jumping off stuff. “I jumped off every little thing I could. I didn’t really know what to do once in the air or how to land, but I loved the feeling,” he remembers.

Watching Tanner Hall and Pep Fujas from a distance inspired Joss to strive for style. Even before that, Chuck introduced Joss to other locals who were making a name for themselves, such as Stefan Thomas and brothers Max and Tosh Peters. Joss’ skills were good enough that he spent most of his time on the hill with older skiers. By his own admission, this led to an “oversized attitude” at a young age. This might be surprising to anyone who knows him today, but it was formative in Joss becoming the man he’s grown into. “I was bullying kids, talking back,” says Joss. “I had baggy style with grownout hair, and I was wearing headbands— just a total punk.”

It was his father who started to step in and remind him of who he really was. “He always knew how to talk to me in the right kind of stern way. He made me realize, ‘Whatever I’m doing, it’s really bothering my father.’” JD’s opinion always mattered to Joss. “He was great at teaching me to be a good person. He taught me a lot about respect and how to be polite.” This guidance from his father, combined with a painful injury at 14, stirred a course correction for Joss. “When I broke both my heels, I had a lot of time to sit around and think, ‘I’m just coasting. I’m not really thinking about what I’m doing. I’m not thinking about who I want to be.’ I spent a lot of time at home and realized I had to be nice to people.”

Nowadays, Joss is universally recognized as one of the most genuine and humble athletes in the game. It’s fitting, then, that his heroes at one point were Duncan Adams and Derek Spong—two talents both known for similar off-hill demeanor. Adams comments, “Joss has always been like that—an antidote to the egomania that’s so easy to adopt on the top-tier competitive circuit. Humility and self-promotion don’t mesh well, which is probably part of the reason he flew under the mainstream radar for so many years. Even so, the links between his genuine personality and his skiing are easy to spot. He’s got this understated style that you just can’t fake, this subtle fluidity, void of all showiness without being robotic.”

While Christensen certainly has a reputation for being Mr. Nice Guy, his longtime friend Alex Schlopy reiterates Mom’s assertion about Joss’ grit. “He may act like the nice guy, but he’s a tiger underneath his little kitty disguise,” he says. And Joss can be pushed too far. He has no tolerance for disrespect. The only time he’s ever been in a fight was an incident on another trip to New Zealand when a drunken Kiwi went too far with a female friend. That guy went down.

This iron determination that lies beneath the surface served Joss well during the grueling road to Sochi.

Three days before competing in the Dew Tour at Breckenridge, he learned a switch rightside double cork nine, and then took that to ten. He now had the back-to-back switch double 1080 in his arsenal, “which you basically had to have to make finals,” he explains. Joss was feeling like he had a chance at qualifying for the Games by being in the top four on the American roster, but he was fighting against some of the biggest talents in the sport and everyone was pushing it: Tom Wallisch, Bobby Brown, Nick Goepper, Gus Kenworthy, Alex Schlopy, McRae Williams.

Joss was in the hunt, but by the time the last qualifying event rolled around, he was all but out of the race, on account of some disappointing results. It all came down to the final Grand Prix event in Park City, his home turf. He had to win to have a chance. And that’s just what he did. With one of the best runs anyone had ever seen. Mike Jaquet, chief marketing officer for the United States Ski and Snowboard Association, remembers, “Going into that weekend in Park City, Joss was not much in the discussion, actually. But his one run was the best run of the year—by score, by difficulty, by variety, by tricks. By any measure, it was the best run we’d seen in multiple years, rivaling anything the sport had seen, really.”

Watch: Joss Christensen’s winning run from the U.S. Grand Prix at Park City Mountain Resort.Listen: Freeskier speaks with Joss Christensen following his win at the U.S. Grand Prix, PCMR.

It took a few days of uncertainty and angst before the decision was announced, but by fighting his way to consideration for over a year and then shining when the pressure was on, Joss landed the final discretionary spot on the Sochi-bound slopestyle squad. The team coaches seemed to know what others did not and took a calculated risk, leaving some bigger names, most notably Tom Wallisch, off the team. The skiing community freaked out, and there was a lot of indignation shared via social media. This was tough for Joss, who has long idolized Wallisch, and he was privy to what so many others did not yet understand— that Wallisch had been skiing through an injury and that he was not 100 percent for the Games.

On the phone: Christensen reacts to earning the coaches’ discretion spot.

But Joss had Wallisch’s blessing. “If I wasn’t going to go, out of everyone, [Joss] was the one who was skiing the best and had the best opportunity to do well,” Tom says. “They made a good choice. I remember talking to him the day he got the call. He felt so bad talking to me. He was being so nice. He didn’t think he deserved it. ‘I feel bad,’ he said. I told him, ‘No! Don’t feel bad. Go crush it.’” And we know what happened next. Joss continued to progress right up until the big show. There’s the now famous story of Joss learning the triple cork just days before the competition. There’s the victory lap. But then there are the moments that the 26 million people didn’t see after Joss’ first run of finals. Like the moment with the crows.

Back in Breckenridge, six months earlier, Sammy Carlson had told Joss about how crows are regarded as spirits of the mountain. “I haven’t really believed in that kind of stuff before,” Joss explains, “but on the chairlift that day in Sochi, Bobby, Gus and I saw three crows that circled us continuously. I just kept staring at one. I swore my dad was hanging out in the soul of that crow.” Joss took that feeling into practice and the competition. He felt a new energy. He couldn’t fall. “I gained a power. The ability to not think. I’m sure there was a crow flying over me during my run.”

And with a score of 95.8 under his belt, Joss then took the sled tow back to the top of the course. “I waited for the driver to go over the knoll, and then I was totally alone before my second run. It was one of those feelings—I felt like I got knocked out in practice and that this was a coma-dream or something. It was just a perfect winter day. But that run, that’s what I was looking for. That was it. It was the most powerful thing I could have done. I just let out a yelp. I threw my skis and was fist pumping. My music was still bumping, so I don’t even know if anyone heard me or saw me. But it was the first time I really smiled. Not forcing it. My body smiled for the first time in almost a year. For a while, I thought this was unachievable.”

That’s how Joss claimed it. Alone with the crows. But he wasn’t in a dreary hotel room now. He was at the Olympics, about to drop in for a victory lap in front of the world. Letting his skiing do the talking once again.

Right after the event, still in Russia, Joss went to a hockey game with Olympic legend Jim Craig, the United States’ goaltender from the 1980 “Miracle on Ice” hockey team. Craig pulled Joss aside and gave him a bit of golden wisdom. “Watch out,” he said. “Enjoy it. Don’t let the circus get you down.”

Listen: Joss Christensen recaps his experience in Sochi.

Joss traveled straight from those words into the Today show, Letterman and Rolling Stone magazine and was almost always joined by the silver and bronze medalists, Gus Kenworthy and Nick Goepper—together, the media-coined “boy band.”

The United States’ sweep of the first-ever Olympic ski slopestyle podium was newsworthy on many levels, and the three got a lot of airtime. “I got real caught up with it for two or three weeks,” Joss tells me. “Interview to interview and the same questions. Gus’ puppies. My father. I feel a bit like I had the opportunity to give the sport to the world.” And in the heat of it all, the reigning gold medalist was still the one most under the radar. His humble demeanor was somewhat overshadowed by his more vocal medalmates. While the big sweep garnered more public interest, Joss sharing the spotlight sometimes exacerbated his shyness and tendency to let others do the talking if given the choice.

https://youtu.be/tilufyBvx5A

Watch: Joss Christensen, Gus Kenworthy and Nick Goepper appear on Letterman.

Wallisch says, “Joss is so grounded. And now with a gold medal, he’s the same guy that I met all those years back. It’s nice to know that success doesn’t change a person. He sets a great example and is just a great person to represent the sport.” His coach and friend Skogen Sprang agrees, “Amazingly enough, I don’t think Joss has really changed since the Olympics. His genuine character and humble attitude has kept him very level headed and still one of the nicest people in the ski industry or world.”

Joss is still adjusting to being a gold medalist, but the roadshow is over and his talk show suit has been hung up for now. Winning Olympic gold helped him realize what he’s truly capable of as a skier. And while Joss is not entirely comfortable with the newfound celebrity, he understands and appreciates the opportunity. Now, he’s back to focusing on the most important thing to him—letting the skiing do the talking.

Related: Track Joss Christensen’s speed, airtime and jump distance in an all-new video from Trace

Note: This article appears in FREESKIER magazine Volume 17.6. The issue is available via iTunes Newsstand. Subscribe to FREESKIER magazine.