Skiing among landmines and bullet holes

WORDS & PHOTOS • Johan Stålberg

“Yes, there are still landmines on the mountain… but here, have a taste, I made it myself,” said a local skier, while waiting for the lifts to open. He was dressed in an outfit straight out of the ‘80s classic, Blizzard of Aahhh’s, and handed us a plastic bottle filled with moonshine before reaching for a cigarette in his pocket. Skiing wasn’t the first topic that came to mind when I thought of Bosnia-Herzegovina. But Sarajevo surprised me and I’m now convinced it should be on the bucket list of any skier with a knack for adventure and an affinity for world history.

Sarajevo and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The names immediately bring to mind the 1984 Winter Olympics and the bloody Bosnian War in the early 1990s. Few outsiders would think of it as a ski destination, and the lack of crowds there wasn’t a surprise, since the majority of skiers, including myself, look to travel to the bigger mountains of North America or Europe when planning a ski trip.

The skiing around Sarajevo is dominated by two ski resorts, Jahorina and Bjelašnica, neither of which boasts the biggest peaks, longest runs or highest cliffs in the world. Here, we found mostly low-angle, gladed terrain easily accessible right off the side of the lift. This suited me very well, as my “ski legs” significantly decreased in strength since moving from a ski town to Stockholm. I used to work as a professional ski photographer, skiing almost every day with Åre as my home base; but, nowadays, I shoot mostly fashion photography, and spend the majority of days buried in designer clothes, rather than deep snow. While the terrain was tame, I’d soon find there’s much more to this slice of the Earth than just the skiing.

SKIER: Andreas Lundstam | LOCATION: Jahorina, BIH

Sarajevo seen from the top of Bjelašnica.

As one of just a handful of skiers in the trees, I made solitary turns on top of golden powder. Lap after lap, my childhood friends Andreas and Kristofer Lundstam and I skied through the forest along the lifts in Jahorina. Our laughter was interspersed with the swishing sounds of us slashing through the snow. After a while, I stopped and noticed something unusual: It was late in the afternoon and I didn’t see any tracks in the snow. I scanned the clean sheet of white for any hint of contrast.

“There, I see a track!” I exclaimed, and pointed towards some firs.

“Those are our tracks from two laps ago,” said Kristofer.

“Yeah, and those tracks over there are from our last one,” Andreas weighed in.

Never in my wildest dreams had I, nor the Lundstam brothers, imagined being all alone skiing powder at any ski resort, anywhere. But in Sarajevo, it was the reality. Each lap, we kept crossing our own tracks through the forest of firs, without seeing another skier. When we got back to the lifts, the lines were just a few people long and I quickly established that we were, in fact, the only ones with skis boasting waists above 100 millimeters. Most people used rental skis and donned decades-old apparel. This was such a contrast to the days I usually had back at my home resort in Åre; after a snowfall, people clad in the latest ski fashion go bat-shit-crazy to get first tracks, sometimes a bit aggressively.

Bjelašnica is the smaller sibling of Jahorina, but it packs more muscle. The ski area has eight lifts and eight miles-worth of trails, along with a small base area that’s more a collection of private housing than a mountainside village. Bjelašnica wins in terms of run length and quality of off-piste skiing. The terrain was steeper and had more flow; it provided us a skiing playground with frost-clad trees straight from a wintertime fairy tale and a variety of runs that could’ve kept us occupied for days.

The moment the Lundstam brothers and I stepped into Restoran Benetton—the local restaurant located a stone’s throw from the chairlift—for lunch, we quickly realized that this was the spot for local freeriders. Peering through a haze of cigarette smoke and espresso steam, we noticed a group of rough-looking skiers, sitting on worn-out benches, ski-boots hung over their shoulders, eyeing us up. To my surprise it was not the evil eye that we met; rather, it was a warm look of recognition that we’re diehard skiers, too, and that it was perfectly fine that we were not from there. They greeted us with hugs, pats on the back and stories of their local mountains. It warmed me inside to encounter locals with such genuine happiness to meet visiting freeride skiers, rather than the cold shoulder I’ve felt in other, more popular European ski towns.

We headed back out onto the hill, and once again, the insane hunt for powder and first tracks was absent. We occasionally met another skier in the frosted forest, but we managed to do several laps before crossing paths again.

I don’t know if it was the terrain on the mountain, the fact that you could see the Sarajevo skyline from the top of the resort or the friendly locals that made Bjelašnica so special. But one thing was for sure; it quickly made my list of unforgettable experiences. For me, it didn’t matter that it wasn’t as hardcore as Chamonix, expansive as Whistler or glitzy as Aspen. It was the friendly and welcoming people, the convenient proximity from downtown Sarajevo, the perfect mix of skiing, city life and a rich history, that made the trip.

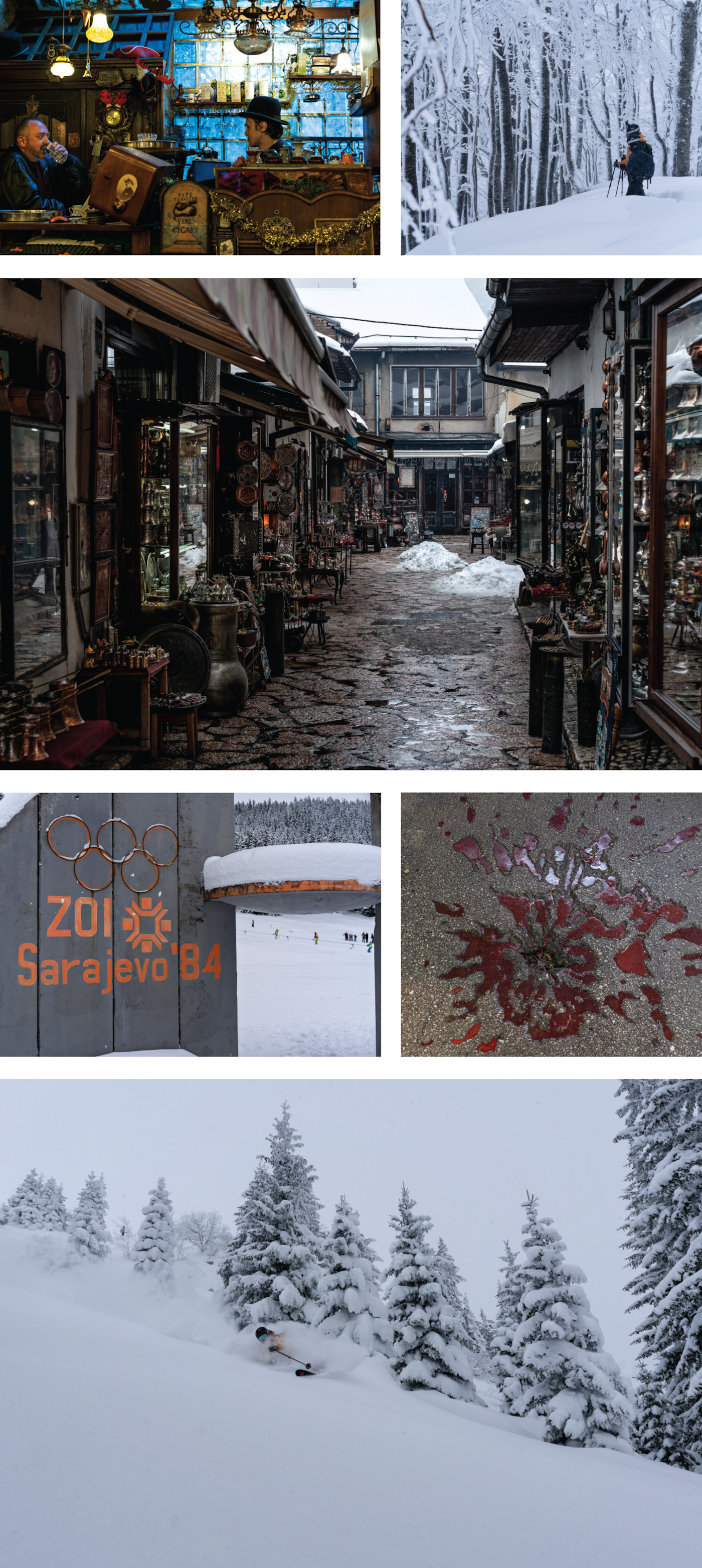

Sarajevo’s past was in view each time we reached the bottom of the lifts at the ski areas—logos and posters from the 1984 Winter Olympics were plastered on all of the restaurant walls, street signs and shop windows around town. Sarajevo beat out Sapporo, Japan’s fifth-largest city, by three votes to become the first socialist state and Muslim-majority city to host a Winter Olympic Games.

The Winter Olympics was a boon for Sarajevo, providing incentive for major development and putting the city on the map. Prior to 1984, neither Jahorina nor Bjelašnica had much more to offer than two small ski hills. Skating and ice hockey rinks, bobsled and luge courses and new ski runs and jumps had to be developed from the ground up to manage the requirements of a worldwide spectacle.

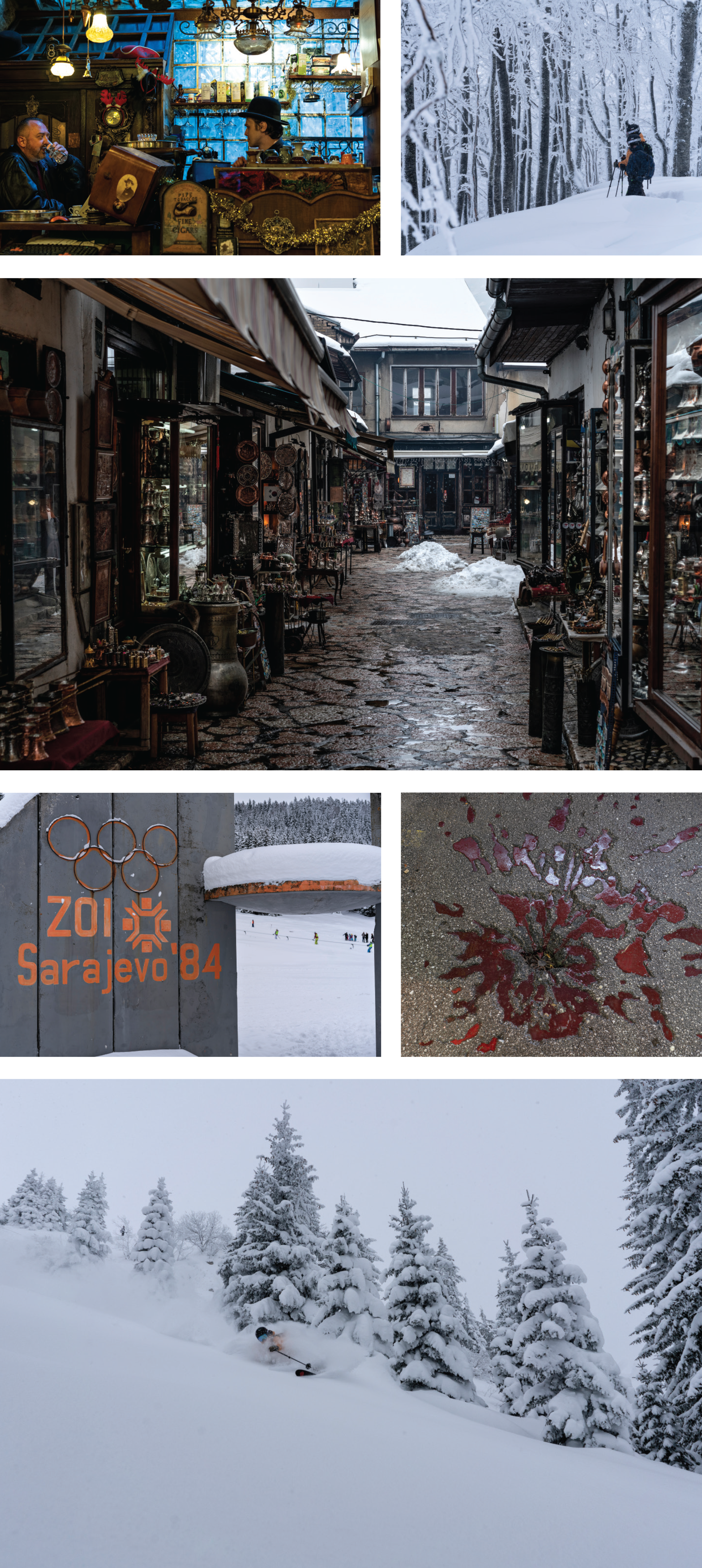

A small bazaar in Sarajevo’s oldest hotel.

Old town Sarajevo.

One of the many back alleys in Sarajevo.

Ten years later, the Bosnian War ravaged the city and surrounding mountains. Traces of the conflict were everywhere: run-down or abandoned apartments near the ski resorts, buildings bearing bullet hole scars that never healed. The tragic history of Sarajevo was ever-present.

We drove past the Zetra Olympic Hall, and our trip guide, Rijad, born and raised in Sarajevo, told me that the soccer field connected to the arena was converted to a graveyard during the war to bury the more than 10,000 who died in the siege, when Bosnian Serbs invaded with the goal of creating a new Bosnian-Serb state. Hearing that made me feel nauseous. A location built to bring so many people together for the love of sports was a mass burial ground just a decade later.

The beautifully named “Sarajevo Rose” also has a much darker and macabre story than its label would suggest. The “Roses” are explosion craters from mortars that were fired over the city. These marks were filled with blood-red resin to honor the people that lost their lives in battle. Walking around the city, these heart-breaking memorials crept inside me every time I saw one, even if they were meant to be a gesture of tribute.

In spite of the vivid reminders of hardship surrounding us, Rijad told me heartwarming stories of the indomitable and warm spirit of Sarajevo’s citizens during wartime—the same friendly, optimistic attitude we experienced from the freeriders at the local watering hole. Sarajevo’s unofficial slogan, coined by the locals during the Olympics prior to the war, was “Sarajevo, The City that Loves People.” I can attest that the slogan is more on point today than ever. Rijad’s anecdotes about how the citizens of this city maintained this spirit of openness during the war reinforced the mantra.

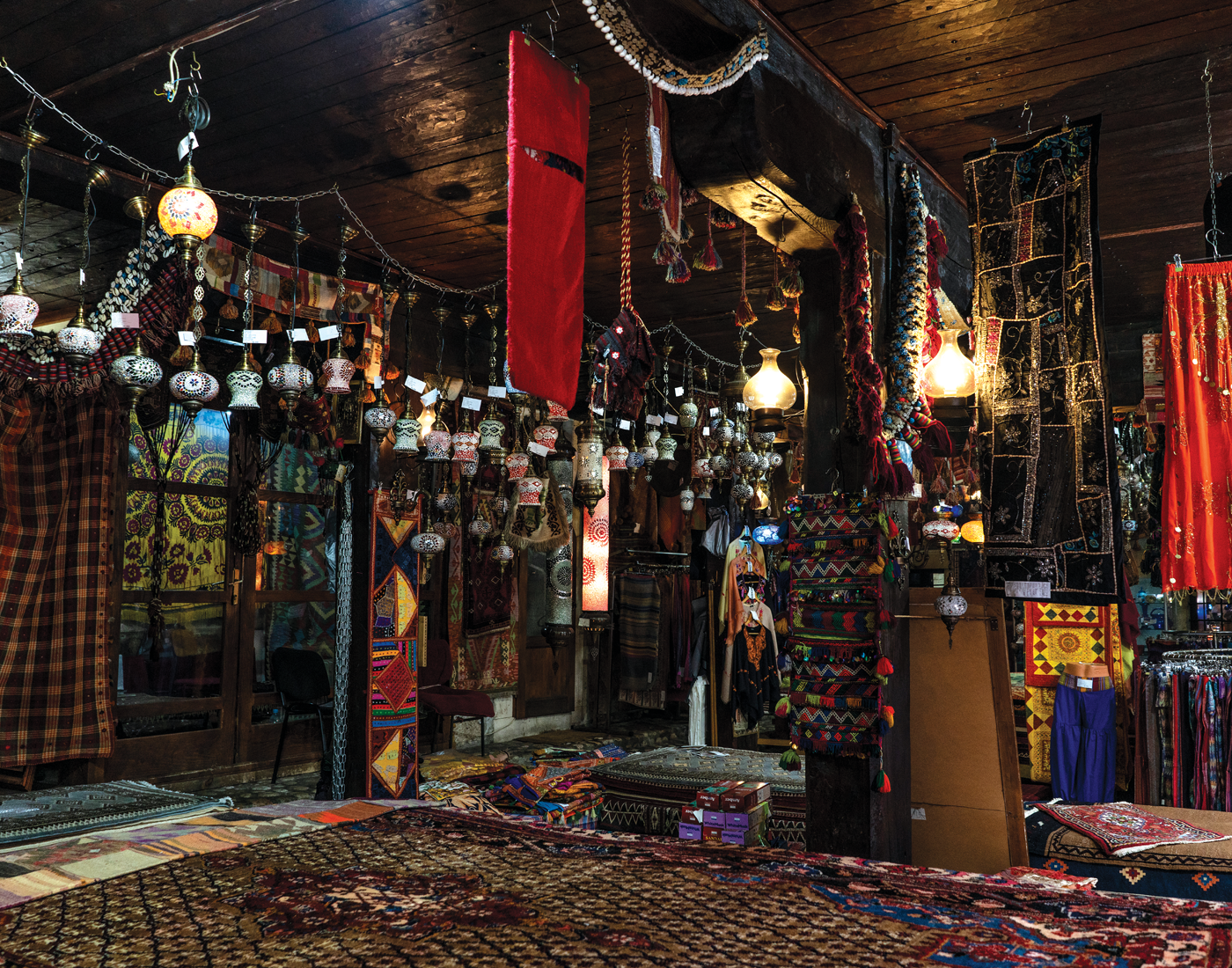

SKIER: Andreas Lundstam | LOCATION: Belašnica, BIH

“If you ask someone to tell you about the war, they don’t start with how horrific it was, but tell you about the more comedic side that took place in the everyday life,” he says, as we stood at the mouth of the Tunnel of Hope, an underground passageway built in 1993 to smuggle food, weapons and medicine into the city under the noses of the Serbian Army.

His cousin, for example, used to bring home firewood from the battlefield so his family and neighbors could cook and warm their homes. But, after some time, all of the small trees had been chopped down, and only large ones were left. Unable to chop the big ones down, he’d find a group of them, and instead, climb to the top and fire his rifle in the direction of the Serbian Army.

“Then he climbed down as fast as he could and took shelter while the mortar shells rained down,” said Rijad. “When they stopped firing, all he had to do was pick up the freshly ‘chopped’ trees and start walking home.”

He also told me of the time, during the war, when his grandparents were tending to their garden and a bombing attack began. They ran into their make-shift greenhouse, constructed of simple nylon, for shelter. After a few moments, however, they realized how completely unsafe they were, and just burst out in laughter at their predicament. This says a lot about the mentality of the people here in Sarajevo.

Beggars and the homeless are another rare sight in Sarajevo. “We take care of each other here, just as we did during the war,” he says. “No one should have to be forced to beg for food or have no place to sleep.” Similarly, the local freeriders in Bjelašnica, instead of keeping the good stuff for themselves, invited us to tag along for a ride and bought us coffee to enjoy as we listened to stories about the mountain we were about to ski.

Skiers visiting Sarajevo can look forward to a two-fold adventure. The lack of ski tourism makes for a tranquil, almost spiritual experience while the ski areas’ proximity to Sarajevo offers visitors the opportunity to immerse themselves in the raw history of a city that’s rebounded from modern warfare.

Skiing Sarajevo is a satisfying, unique experience and the backstory of the place is worthy of a University seminar, but it’s the people of Sarajevo that turned my visit from a regular ski trip to a lifelong memory. The residents of this city want their home to be recognized as the welcoming and beautiful place it is, not for war and bloodshed. Everyone wants to wash away the image of the Bosnian War—and you can really feel it. Never have I ever felt so welcomed as a visiting skier than I did here in Sarajevo. There’s no competition among the skiers here, just an eagerness to share a great run on their home mountains. Everyone here lives to show the world what Sarajevo really is—the city that loves people.

Sarajevo International Airport (SJJ) is the main airport hub in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and is less than an hour’s drive from Jahorina.

Low prices and a favorable exchange rate ensure that being indulgent won’t empty your wallet. We stayed at the five-star Swissotel, a newly-built high-rise hotel located in the heart of Sarajevo. It was the perfect home base to explore the city.

Food isn’t Bosnia’s biggest draw, but I can recommend the Staza restaurant in Bjelašnica and Rajska Vrata in Jahorina. They serve very good Bosnian-style goulash and great meatballs. In Sarajevo, there was no shortage of great restaurants. Klopa was a hidden gem, located close to the old town. We were served the most delicious cuisine made from local Sarajevo ingredients. The locals’ spot was Kibe Mahala, which had a beautiful and almost Bohemian interior, with walls adorned with photos of A-list celebrities who, just like us, had found their way up the hillside for a genuine Bosnian dinner experience. Who knows, maybe we sat at the same table as Morgan Freeman or Robert DeNiro.

This story originally appeared in FREESKIER 22.4, The Destination Issue.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a YoColorado X Coors Banquet & Liberty Skis Prize Package](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1769630228-pastedgraphic-3.png?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)