Adventure is guaranteed on the roof of the Andes

WORDS • Ben Hoiness | PHOTOS • Fredrik Marmaster

We started planning this trip a year ago after seeing some photos in the American Alpine Journal. We were hoping to explore Bolivia’s Cordillera Real range—a 125-kilometer-long stretch of densely glaciated granite peaks largely unexplored by skiers. Our group of three knew skiing in Bolivia would be challenging because of the weather, the complicated and glaciated terrain and the lack of beta. The scale, remoteness and subsequent mystery of these mountains are what keep most people away. But it’s also what draws people like us in to explore.

Zahan “Z” Billimoria, Fred Marmsater and I arrived in Bolivia’s capital city of La Paz late on a Thursday night. The city, which sits at 3,640 meters and is home to 3 million people, was bustling and even at that late hour, its cobblestone streets were filled with people, cars and vendors selling everything from electronics to hand-knit sweaters and salteñas—empanadas made Bolivian-style with onions, peppers and meat.

Although the Real range is two hours from La Paz, the city is the perfect starting point to acclimatize. A year of planning and thirty hours of travel had finally brought us to these wild mountains that guaranteed adventure. Sleep came easy that night.

We planned to stay in La Paz for four days, but by the next evening, we were getting antsy because, well, the weather looked good. The weather is pretty much all people talk about when it comes to skiing big peaks in unfamiliar places. It was May—Bolivia’s Astral Fall and the transition period between the wet and dry seasons. The peaks had just been received some precipitation, meaning we could hit higher elevations in a clear weather window with soft snow.

“What if we just left for Sajama tomorrow?” Fred proposed, referring to the national park 250 kilometers to the south. The weather wasn’t optimal east of us in the Reals yet and Fred thought taking our acclimation mission to a few easier and smaller peaks in Sajama was a good idea. Z and I agreed.

Ben and Z acclimatize on 6,282-meter Pomerape. Sajama National Park is filled with a number of quality ski objectives.

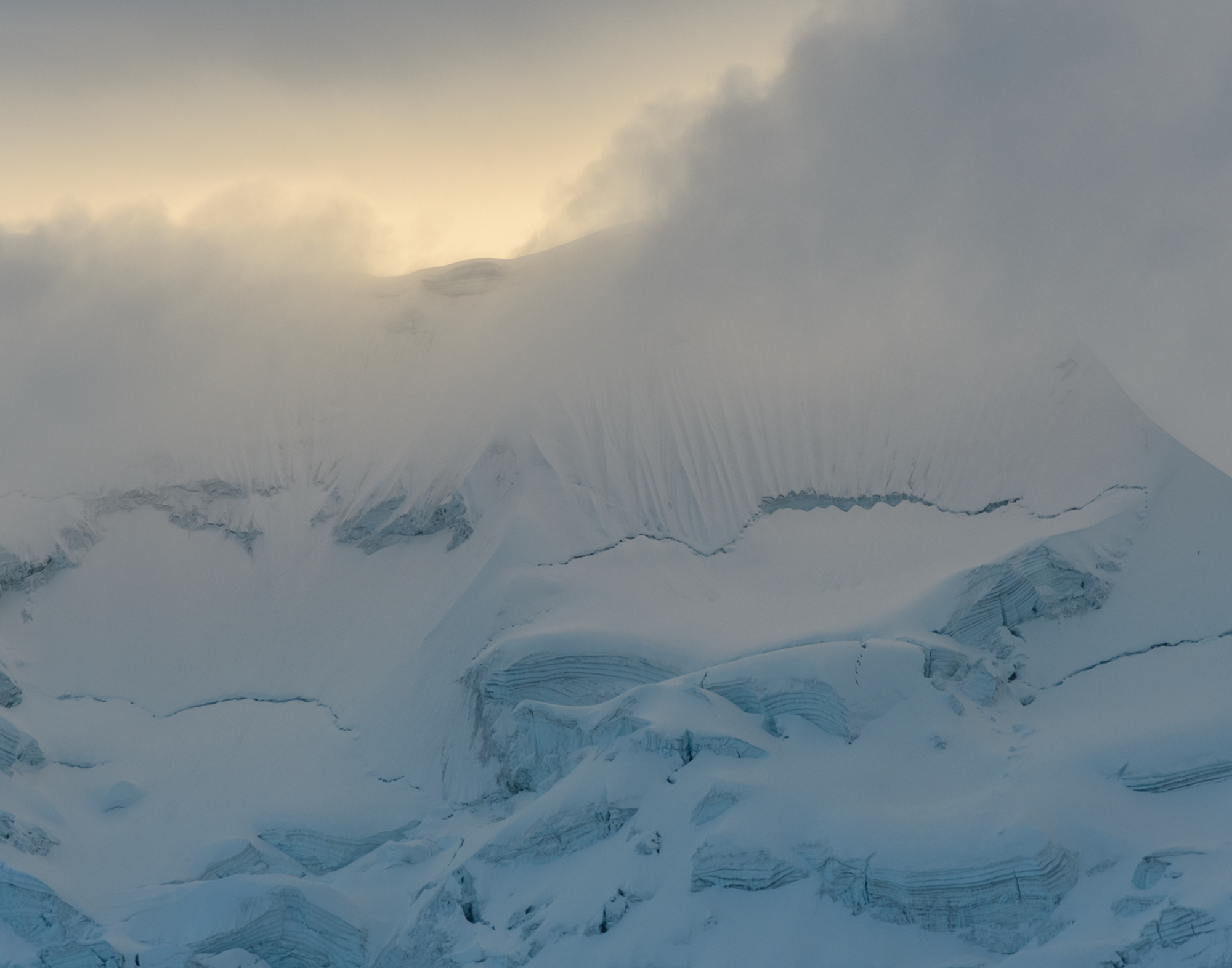

One of the spine walls on Illimani, one of the main reasons the crew wanted to travel to Bolivia.

In the morning, I crawled into the back of a mini-bus with a fuzzy maroon shag rug covering the dashboard. Our driver, Valentino, was clean cut and punctual. He lived in La Paz his whole life and could drive the narrow roads fast—really fast. Also along for the ride was our cook, Wenceslao, who was a gregarious character boasting more gold teeth than white.

After a few hours, high-elevation sagebrush desert—the Altiplano—replaced the city landscape and we arrived in the small village of Sajama at 4,200 meters. Volcanoes dotted the landscape; up near 5,100 meters, the brownish-green scenery faded into white and two muscled volcanoes, Pomerape (6,282 m) and Parinacota (6,380 m), looked down on us. We would try to ski both in the coming days.

We moved our bags into a thatched-roof hut. The walls were pink and the beds were made from brick and cardboard. Wenceslao made us chicken soup and coca tea to settle our stomachs, which churned at this elevation.

In the morning, we took a two-hour ride—with one short stop so the driver could run his alpacas back onto his land—to the base of Pomerape. We began our ascent walking on pumice and after a few hours, reached the snowline. The altitude didn’t hinder us significantly until we hit 5,700 meters; all of a sudden, it felt like someone was slowly tightening a vice grip on my head. It was our third day in the country, but our first at substantial altitude.

We were just 100 meters below the summit when I decided to ski down. The 1,000-meter descent was perfect corn, but every time I pressured my edges I felt the reverberations all the way to my brain. Fred and Z were feeling better than I was, but were happy to accompany me to a lower elevation. Thanks, guys.

Ben Hoiness descends 6,438-meter Illimani in surprisingly pleasant conditions.

Back in town, my stomach turned sour and any food further stirred it into a frenzy. Despite my condition and a marginal weather forecast, we decided to go for Parinacota the following day. We reached 5,700 meters before two storms—one on the mountain and one in my stomach—forced us back down.

At the 4×4, I laid on my back with a grueling headache, drinking apple juice and wondering if Bolivia was going to kick my ass the whole time. Shortly after, a blizzard engulfed the area around me, disturbing my lounging and signaling the end of our stay in Sajama.

We spent a few days back in La Paz gearing up to head into the Cordillera Real with our sights set on the peak that had piqued our interest for over a year, Illimani (6,438 m).

The 200-mile journey to Illimani was on one of the worst roads I’ve ever been on. Thankfully, I’d gotten some antibiotics that eased my stomach bug before we left La Paz that morning. The mostly-unpaved road took six hours to drive, all while skirting a 900-meter cliff that dropped off one side during certain stretches. We drove until the road ended and then walked for two hours with three porters, two donkeys and Wenceslao, who, in addition to being our cook, turned out to be the group’s spiritual leader. Our destination was described to us previously as one of the most beautiful base camps on Earth and we weren’t led astray.

In the morning, we climbed a broken rock ridge and traded crampons for skis and skins at 5,600 meters. I seemed to be acclimatized enough for my headaches to subside. The terrain was spectacular on both sides of the ridge. We were surrounded by perfect, steep, powdery spine walls that ended in impassable ice falls underneath seracs that calved off every hour or so and boomed down on the glacier below. An unforgiving approach guarded these spectacular, unskied walls and we racked our brains to devise a way through it as we continued up the ridge.

Ben and Z, scoping lines from base camp.

The author replenishes with apple juice, just before the storm.

As we moved higher, the thin air forced us to slow down. We’d take five steps, then break, five steps, then break. We turned around at 6,200 meters because of weather. For the third time, we stopped shy of a summit, but I wasn’t disappointed in the slightest. The stark contrast between the snowy, wintry landscape where we stood and the swirling brown-green high desert below made us forget all about the inconsequential act of tagging the summit. And, we skied boot top powder that transitioned to corn all the way down to the snowline—hard to complain about that.

Back at camp, Wenceslao made us soup, popcorn and fried pork, and offered up some Coca-Cola to wash it down. As he cooked, he told us tall tales in broken English. In one story, he said that some people came into a base camp in the high Andes and stole some supplies, then Bolivian porters caught the thieves and burned them at the stake. Later, we watched him attempt to whisk away oncoming lightning by throwing Coca-Cola into the air.

The next day we rested, killing time by talking about the weather and eating potatoes. Our plan was to gear back up to ski Illimani the following day, but the weather looked questionable. Wenceslao kept telling us that a storm was coming and that we should go back to La Paz, but we couldn’t decipher if he was telling the truth or if he just wanted to go see his girlfriend. A storm did eventually move in, thwarted our hopes of getting back on Illimani, drenched our base camp and sent us back to La Paz.

After a few days resting and waiting on weather in La Paz, we decided to head up north to Sorata to make an attempt on the beautiful Ancohuma. The forecast looked promising and our morale was high. The journey to Sorata brought us down to 2,400 meters for the first time since we left the States. The air felt thick and it was wild to be down in the jungle preparing to head up to a glaciated peak just hours later.

We were able to drive to 3,900 meters and from there, we hiked to an inconceivably beautiful base camp at Laguna Sorata, just over 4,800 meters. The glacier we would climb the following day was calving into the lake periodically throughout the night, which, in combination with the high-altitude camp, made sleeping fairly difficult.

One of countless farming villages along the road from La Paz to Sorta.

The sun sets on base camp below Illimani, 6,438 m. The crew had this meadow to itself for a few days before a huge western expedition moved in.

It wasn’t long before I found myself raging war at 5,700 meters again, but this time I felt pretty good. We all battled with a South American stomach smackdown at some point along the way, but finally we all were feeling and moving well. Bagging the west ridge of the immaculate Ancohuma, the third tallest peak in Bolivia, was sublime. It was a steep and beautiful mountain with a gentle glacier leading to its summit headwall. When we reached the top, we embraced the summit with a short nap, but didn’t forget to take in the dichotomy of the Altiplano colliding with mighty summits that stretched the horizon underneath calm weather. We skied soft powder down the west ridge into the southwest face of the peak. It wasn’t a technical line, but we were happy to put the first tracks down it. We party-skied down the glacier in dreamy conditions that cut through the clouds. Wenceslao greeted us with popcorn, soup and shared stoke for our descent.

The next morning, we hiked out and drove back to La Paz. We went to an asadó, a South American barbecue, with Fabricio, our logistics coordinator, and his family. The spread was out of this world; his brother was a chef and prepared steak with chimichurri, spicy salsa, four different potato dishes and our first salad in two and a half weeks. We spent the evening drinking red wine, sharing stories, talking politics and reminiscing on the trip up to this point. His family was incredibly welcoming to us.

Ben and Z pose with the local guides who inherited their skis.

There was time for one last mission before heading back to the comfort of lower altitudes and the States. Our choice was the “French Direct” on Huayna Potosi (6,088 m). After one last violently bumpy car ride, we found ourselves hiking towards the refugio that was at the base of the mountain. Huayana Potosi is the most popular mountaineering peak in Bolivia and although we had to share the mountain with other climbers for the first time on the trip, it was still an incredible experience on another overpoweringly big peak. We snuck around the back side and dropped in top down on our last objective. The descent was perfect; the pitch was steep, the snow dry, and the view looking out over the brown and black desert that surrounded La Paz and the Altiplano was out of this world.

We arrived back at the Refugio to a group of local mountain guides cheering and applauding our descent. It was humbling to see how excited and welcoming they were to us. We shared tea and Coca-Cola and chatted about our trip. They were excited about skiing and asked if they could try out our skis. These guides had spent years walking up and down this mountain, but never with skis on. They ran up a snowfield behind the hut at such a blistering pace that it left us questioning our own athletic abilities. After some minor coaching from us, they took turns skiing and learned quickly. We knew we had no choice but to leave our skis and boots with them. Months later, they still send us updates on their skiing. It was so fulfilling to have been able to gift them that gear after they shared their home with us, inspiring them to explore their own incredible country in a new way.

This story originally appeared in FREESKIER 22.4, The Destination Issue.