Level 1: it’s all in the name. Josh Berman’s ski movie production company started at the bottom, as a kid with a camera filming his friends. Yet, over two decades, Level 1 rose from humble beginnings to become a veritable standard-bearer in freeskiing.

Romance, the 2019 flick from Level 1 Productions, is the twentieth and final annual ski film that the company will produce, marking the end of an era. But, if it wasn’t for some bad medical advice, Level 1 might never have existed in the first place. In January of 2000, Josh Berman landed backseat on an alley-oop five in Stratton Mountain, Vermont’s newly opened halfpipe and felt something pop in his knee. A college student taking the winter term off to chase a professional skiing career, Berman figured his season was over. However, after an initial MRI scan, an orthopedist’s recommendations were encouraging.

The bad news: Berman had no ACL in his left knee. The good news: He’d likely already torn it at some point prior, and the pop he had heard was actually scar tissue tearing loose. His knee now had nothing stabilizing it, but the doctor felt that he wasn’t at risk of further injury. “He pretty much said you can just go out and do what you want to do,” Berman reports. “That was the best thing I could be told. I had just committed to taking the winter term off from Dartmouth. I didn’t want to go back to school. I wanted to be told I was invincible.”

A couple weeks later, Berman was back in the terrain park. He overshot a jump on a switch 180, and his knee collapsed. “My whole left leg folded over backwards,” he remembers. “There was nothing to stop it.” With a torn lateral and medial meniscus and a shattered tibial plateau, Berman’s ski season—as well as his dream of becoming a pro—was now officially over. Uninspired by the prospect of going back to school, Berman got the idea of making a ski movie that winter instead. Urged on and supported by photographer Jeff Winterton, a lynchpin of the East Coast scene, Berman started filming his friends in terrain parks and contests around the region. His leg still in an immobilizer, he maneuvered around on one ski. The product of that season, Balance, was a ski movie with an unusual proposition: The East Coast—traditional butt of many a skiing joke—was actually a hot spot, a desirable place to be for the coming generation of skiers. Berman’s voiceover introduction to Balance says it best:

There exists an unrecognized balance in North America between the level of talent on the East Coast and the rest of the continent. For years, great skiers whose roots lay in Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine and Quebec have been abandoning the East Coast in search of the bluer skies, ample snow and potential exposure out West. Only a few short years ago, before the proliferation of the terrain park and the enlightenment of skiers to a revolutionary skiing style, East Coast skiing represented nothing of consequence or interest to a public that demanded the “extreme.” Things have changed, and for the first time in the long history of ski movies, the East Coast wasn’t shunned in the making of Balance. In fact, it provided the inspiration. Based around some of the sickest up-and-coming East Coast skiers and blended with a generous helping from our western brethren, we’re proud to entertain you with a humble serving of newschool skiing—East Coast style.

A new movement was beginning to shake up the status quo in skiing, and Berman was poised to ride the wave. He took the next winter off from school to film another movie, Second Generation, which captured the explosive vibe of the era: a heady time when new tricks, features and possibilities were around every corner. Berman’s camera was trained on his East Coast crew—rising talents like Andy Woods, Scott Hibbert and Garrett Brittain—but at contests and photo shoots he also bagged copious shots of stars from the wider scene like Tanner Hall, Phil Belanger, Candide Thovex and Mickael Deschenaux. An emphasis on individual style was already beginning to mark Berman’s movies, driven home in Second Generation by the stellar closing segment from an unknown Canadian phenom named David Crichton.

From left to right: Kyle Decker, Josh Berman and Freedle Coty pose for the camera in Denver, CO, in 2009. | PHOTO: Erik Seo

By Strike Three in 2002, the venture had reached a make-or-break point for Berman. He’d graduated from college and was planning to pursue a film career in New York or Los Angeles. His third ski movie would be his last: Strike three, you’re out. “This is my last hurrah traveling the world and playing around with my friends,” Berman remembers thinking. “It’s definitely going to get real after that. Obviously, it didn’t work out that way.”

Strike Three was indeed a turning point for Level 1 Productions. The movie was Berman’s best yet: a jaw-dropping collection of the year’s biggest hits from events like Superpark and Parkasaurus backed up with career-making segments from a strong cast of riders. With flawless style in every movement, Crichton’s segment was a cornerstone of the movie, anchored by a cringe-inducing crash on a bridge rail that still racks up views in “insane action sports moments” highlight reels today. The music also set Level 1 apart from its peers, as the rock and punk tracks standard in the ski movies of the time gave way to hip-hop influence. Level 1’s soundtracks would soon become an essential element of the company’s vibe, stocking skiers’ shredding playlists for almost two decades.

Obviously, Strike Three was not Level 1’s curtain call. The following winter Berman continued his endeavor, bouncing from couch to couch for months at a time, chasing ski events in a widening arc across North America. His next effort, Forward, was another hard-hitting, trend-setting movie that set the pace for what would become Level 1’s fast rise to prominence. With another standout Dave Crichton performance, Scott Hibbert’s legendary crash segment, Liam Downey’s effortless style and an obnoxious young up-and-comer named Simon Dumont, Forward stands today as a classic documentary of what some now call freeskiing’s Golden Era. It was a wild time: No one was sure what new outrageous thing would happen on any given day. Onlookers were getting accidentally body-checked at the edges of rail jams by adrenaline-wired youth on skis. Cameramen who thought they were standing at a safe distance from the knuckle were blindsided when Hibbert and his ilk would suddenly come flying out of left field, smashing lenses and drawing blood.

Berman came to the realization that he could no longer run the company from his parents’ farmhouse in southern Vermont. “This was not a viable business location,” he recalls. “Moreover, there was less and less interest from myself and the athletes in shooting skiing on the East Coast. Clearly, going west of the Mississippi offered a lot more snow, a lot more access to terrain and athletes and everything we wanted to pursue.”

Bitten by the same bug he had once protested in Balance—the inescapable lure of the West—Berman moved first to Boulder, Colorado, then purchased a house in Aurora, a suburb of Denver, the following year. “We packed in a few roommates, put Freedle in the basement closet and called it the Level 1 office,” he recalls. A kid from Stowe, Vermont, whose brother Emil had starred in several of Berman’s movies, Freedle Coty had dropped out of school to film and ski, shot several portions of Strike Three and Forward, and spent a winter in Kirkwood, California, working as a night janitor. He quickly became an integral part of Level 1 as Berman’s trusted co-pilot.

The next three films—High Five, Shanghai Six and Long Story Short—cemented Level 1’s position as a movie company on the rise. Now anchored in Colorado’s Front Range, Berman began shooting more backcountry, while park shoots were arranged at nearby resorts in the springtime. A new cast of skiers—Steele Spence, Travis Redd, Tanner Rainville and Stefan Thomas among them—sprang to the forefront, while the Superunknown contest, a video-based talent search that was a crucial addition to Level 1’s operation, opened what would become a continuous stream of new talent, starting with the first winner, Corey Vanular.

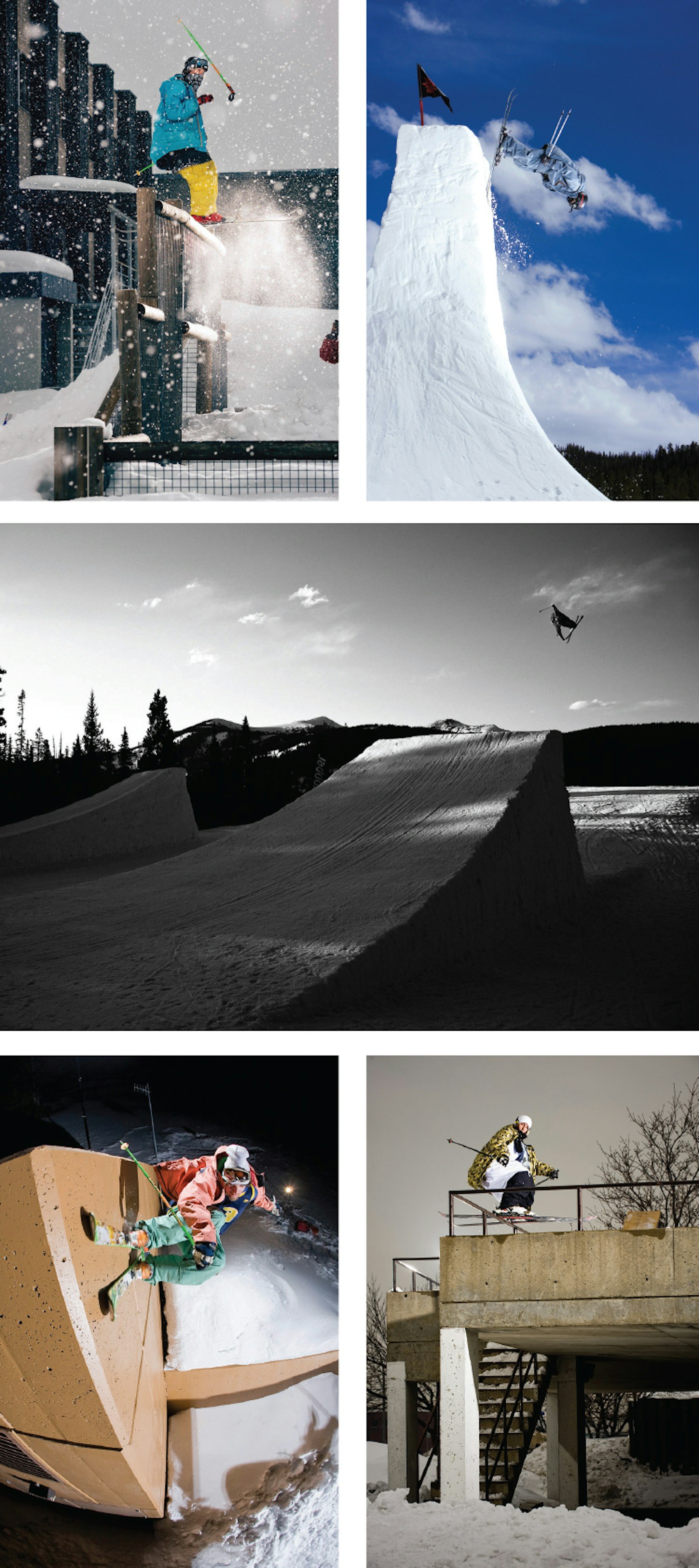

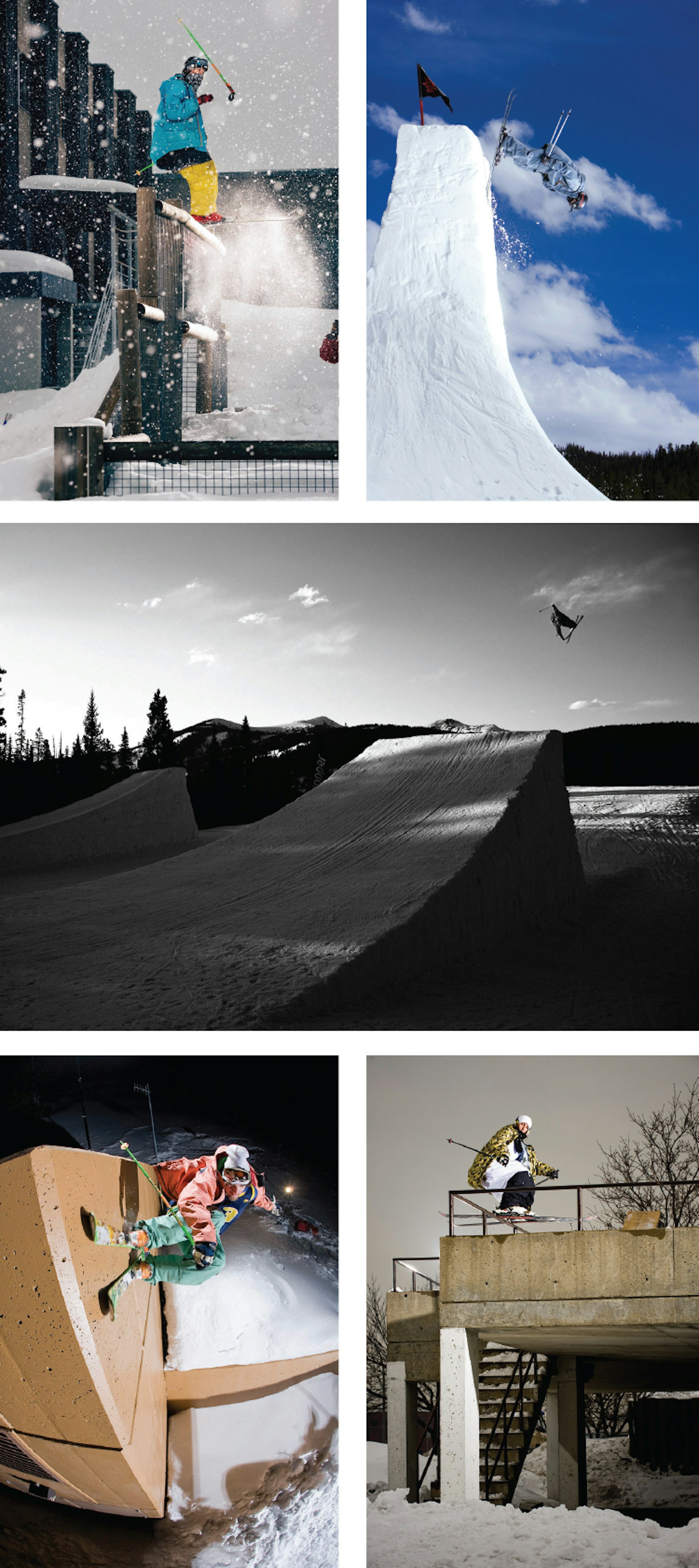

Photo credits, clockwise from top: (S) Tom Wallisch, (P) Nate Abbott, (L) Åre, Sweden / Jon Olsson Super Sessions, 2009; (S) Craig Coker, (P) Jay Michelfelder, (L) Keystone, CO / Realtime, 2007; (S) Adam Delorme, (P) Nate Abbott, (L) Copper Mountain, CO / Refresh, 2009; (S) Phil Casabon, (P) Erik Seo, (L) Montreal, QC / Refresh, 2009; (S) Liam Downey, (P) Erik Seo, (L) Park City, UT / Turbo, 2008

Realtime, released in 2007, marked the beginning of Level 1’s next phase—one that, as Freedle puts it, “might as well be called the Tom Wallisch era.” An incredible talent from—of all places, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—Wallisch made his world debut with his Superunknown entry video, now a timeless piece of skiing history. He was promptly ushered into the Level 1 fold, where he would become one of the skiers most closely associated with the brand. He wasn’t alone; a new generation of style influencers like Wiley Miller, Adam Delorme, Ahmet Dadali, Mike Hornbeck and filmer/director Kyle Decker were each making their mark.

SKIER: Steele Spence | PHOTO: Jay Michelfelder | LOCATION: Whistler, BC / Long Story Short, 2007

The so-called Wallisch era continued through Turbo in 2008 and the company’s tenth movie, Refresh, in 2009. The ten-year anniversary film included a surprise guest narrator—none other than legendary ski filmmaker Warren Miller himself. A resulting lawsuit from Warren Miller Entertainment only served to boost Level 1’s profile, with mainstream media mentions all the way to the pages of the New York Times. Copies of the movie, and the Level 1-branded tall tee that all of the athletes were rocking, flew off the shelves.

Level 1’s operation was expanding rapidly. Schui Baumann remembers walking into the local post office with garbage bags full of DVDs to send out. A design student from Germany who had joined as an intern in 2008, Baumann grew to play a prominent role in the company’s aesthetic and organization, from motion graphics and art design to e-commerce and the growing merchandise arm. His predilection for streamlining processes may well stem from those early mailing trips. “Imagine showing up to a post office, without prepaid postage or anything, and going up to the counter like that,” he says. “I basically shut down a small post office for half a day.”

SKIER: Parker White | PHOTO: Erik Seo | LOCATION: Sun Valley, ID / Sunny, 2012

Berman felt that his company had finally acquired a level of standing in the industry. For years he’d considered himself disparaged as little more than a video cam-toting kid by larger, more established peers. “Refresh was a turning point,” he says. “People started to take us more seriously, like we weren’t just kids making videos with our friends. That was the vibe I’d gotten for a number of years.”

“Level 1 was underground in the sense that it wasn’t on the same playing field as big ski or sports media companies,” adds Freedle. “It really wasn’t until Refresh that I felt we had arrived.”

SKIER: Wiley Miller | PHOTO: Jeff Cricco | LOCATION: Valdez, AK / Eye Trip, 2009

In 2013, however, the crew faced a crisis. Wallisch—by now practically synonymous with the brand—had decided to go his own way to film The Wallisch Project. Harlaut and Casabon had also departed, as had Parker White and Chris Logan. Following this exodus, some wondered if the company’s influence was waning. Berman says that at least one industry figure told him outright that Level 1 was finished.

It wasn’t. They responded in 2014 with Less, a movie that sought to buck the “more, bigger, better” trend predominant in action sports at the time. Without the A-listers it had relied on in previous years, Level 1 looked to return the focus to skiing’s simpler pleasures, exemplified by the new-wave experimentations of innovators like Granér and Stål-Madison, backed up by remaining stalwarts like Wesson, Delorme and Rainville. “It was a reset,” says Freedle. “We didn’t have the star power that we’d cultivated in previous years.”

Small World continued that trend with the ski-movie debut of Sämi Ortlieb, another innovator whose unique visions brought new life to the screen. 2016’s Pleasure and the following year’s Habit ushered in Keegan Kilbride as a new urban skiing hero, while Freedle’s increasing directorial efforts led the movies into ever more creative, eclectic directions. 2018’s Zig Zag saw the triumphant return of Parker White and Chris Logan, while an increasingly European cast, including Ortlieb, Laurent de Martin and Pär “Peyben” Hägglund, brought their visions to life.

This year, Level 1’s twentieth—and final—annual ski movie, Romance, will wow fans of skiing the world over. The film is Level 1 at its best. The company itself isn’t going anywhere: Superunknown and the merchandising arm will continue running strong. Berman and Freedle will continue to produce video content, freed from the constraints of the annual-movie format. “It’s a process we’ve been stuck in for a long time, and it’s a huge release to get out of it,” says Freedle.

The company’s movies have propelled a dizzying array of skiers into the public eye. A quick tally of segments yields up three skiers who have appeared in more Level 1 movies than anyone else: Will Wesson, Wiley Miller and Tanner Rainville. I ask Berman, Freedle and Baumann which skiers stand out for them over two decades. “You can’t underestimate the contribution of Dave Crichton,” Freedle answers instantly. “He established Level 1, in my humble opinion. Corey Vanular helped put Superunknown on the map, and was the first real discovery that Level 1 made. Henrik Harlaut, Phil Casabon, Parker White, Tom Wallisch—these guys have such huge personalities in skiing. They made such a presence in the movies, and left such a void when they were gone.”

“Someone who always gets overlooked, but who’s always been there, is Will Wesson,” adds Baumann. “He’s not the flashiest, but the stuff he’s done has always been game-changing.”

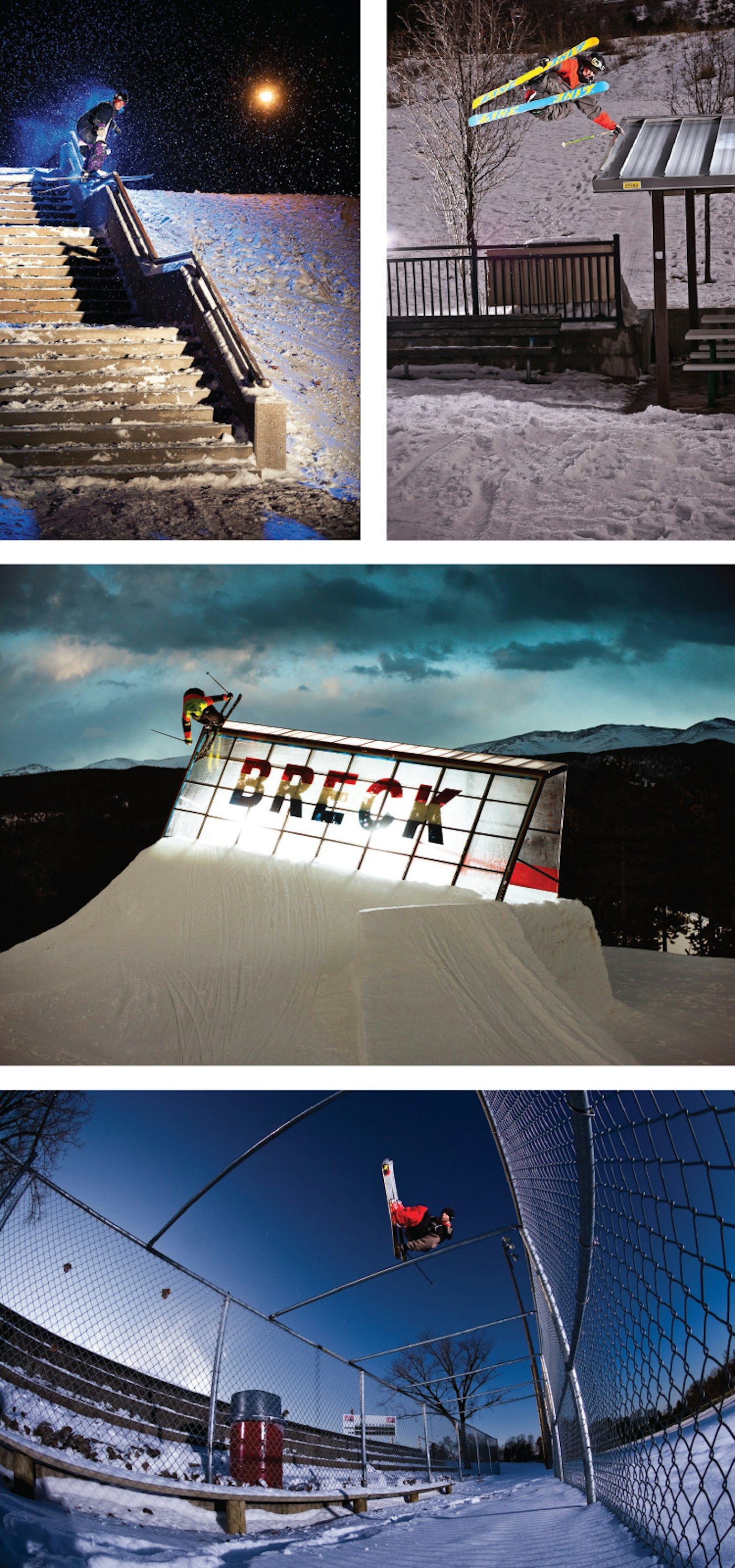

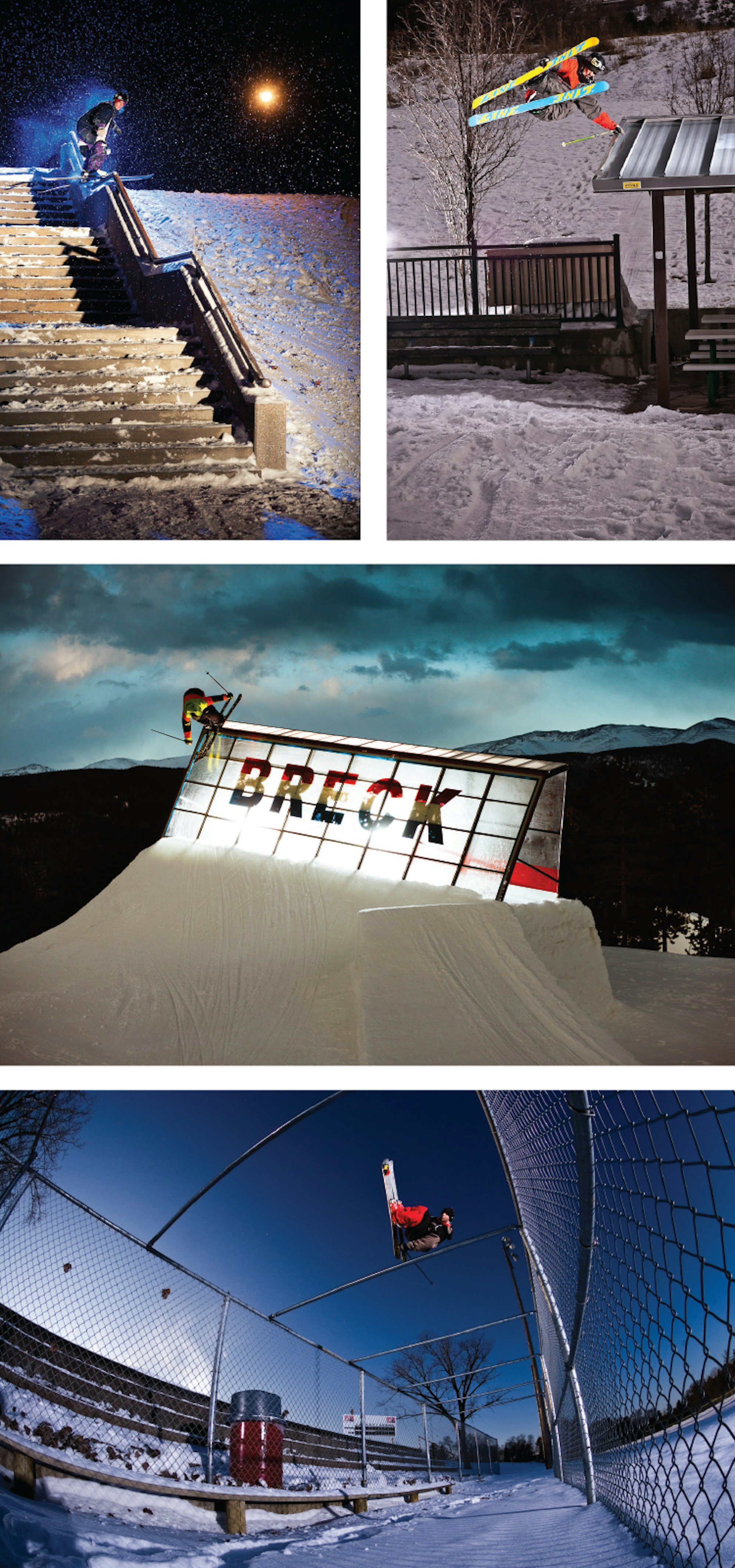

Photo credits, clockwise from top: (S) Henrik Harlaut, (P) Erik Seo, (L) Grand Rapids, MI / Turbo, 2008; (S) Will Wesson, (P) Erik Seo, (L) Salt Lake City, UT / Eye Trip, 2000; (S) Mike Hornbeck, (P) Nate Abbott, (L) Breckenridge, CO / After Dark, 2011; (S) Ahmet Dadali, (P) Erik Seo, (L) Stillwater, MN / Eye Trip, 2000

Regardless of what the future may hold for Level 1, its creators can look back with pride on two decades of blood, sweat and tears that helped to define what the sport of skiing looks like today—a finger always on the pulse of the trends, while never losing sight of the street-hustle mentality from whence the project sprang.

“Level 1 played a huge role in the growth of freeskiing by repeatedly showing that you can grow up in the East or the Midwest and still become a pro skier,” says Wesson. “Keeping that dream alive and giving up-and-coming skiers the chance to showcase their skills to the masses are things that have always set Level 1 apart. I got my start not by winning a contest or having a sponsor pay for me to join the crew, but from friends putting in a good word, and Freedle and Josh giving me an opportunity. Without them taking that chance on me, the last decade of my life would be completely different.”

“Level 1 did a really good job of constantly evolving and changing with all the different tides of skiing, while simultaneously always staying true to itself,” says Parker White. “I think that is its legacy: something that was always changing, and also never changing, all at the same time.”

This story originally appeared in FREESKIER 22.2, The Resort Guide.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a YoColorado X Coors Banquet & Liberty Skis Prize Package](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1769630228-pastedgraphic-3.png?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)