The Mind-Body Fusion of the Backcountry Shredder

What makes some skiers capable of stomping epic lines on towering Alaskan peaks while others are inclined to pee their pants at the thought of trying? How does the adventure-driven skier who aspires to such extraordinary feats actually achieve them? Needless to say, skill, reached through countless days of skiing, is essential. But, skill alone is not enough. It takes a certain mentality to drop in from an icy cornice above a thousands-of-vertical-feet-long, 50-degree slope riddled with crevasses, cliffs and hungry sluff. The obvious answer to this chicken versus egg scenario might be that one develops both skill and psychological strength mutually. As ability, knowledge and fitness increase, one’s mental aptitude does, too. But what does this mean, really?

Hoping to discover the secrets to getting you there, I discussed this phenomenon with several of the world’s top backcountry shredders. I also looked at leading neuro-scientific research on people who engage in high-risk activities, such as gamblers and stock investors, and on those who pursue transcendent experiences through religious rituals, meditation practices or hallucinogenic drugs. The high-tech magnetic resonance and gamma radiation photography scientists use for this research, however, is not mobile, and therefore can only be used to analyze the brain activity of subjects in laboratories. For this reason, scientists have yet to focus on the brains of action sports athletes.

It is widely believed that what distinguishes humans from animals is our capacity to think abstractly and anticipate events, including the actions of others, based on acquired information, comparison and probability. This makes our experiences more profound as well as complex. Mysteries can be exciting and challenging, and such is the mystery of death. The unknown, particularly when the stakes are high, leads humans to extrapolate, and this often causes anxiety and fear. Consider that animals do not respond to the threat of danger until they perceive it through their senses, whereas humans can imagine dangers where they do not exist. Our potential for creative negativity is no stranger to the extreme sports athlete, like the freeskier contemplating an off-piste huck into untrodden, deep pow. We imagine horrible failings, and these thoughts trigger nervousness, which, in turn, sabotage our bodies’ capacities to process information correctly or fast enough to perform effectively. As a result, exacerbated by unrestrained thinking that surges our limbic system—which involves emotions, thoughts, perceptions and memory, and activates functions like adrenaline and dopamine production as well as heightened arousal of the fight, flight or freeze responses of the sympathetic nervous system—the drive toward self-preservation becomes self-destructive, our worried prophecies self-fulfilling.

Fortunately, mental preparations can enable us to dodge this, the most important of which are commitment, visualization, breath-work, self-motivation and appreciation. Pioneer of all-female ski films, Sandra Lahnsteiner, 35, is not just a champion shredder; she’s also the recipient of a Master of Sports Science & Coaching degree from the University of Salzburg who was more than happy to share her expertise and love of the backcountry. “When I am about to drop in,” explains Lahnsteiner, “and we have the count down, I am more to myself, visualizing my line, trying to feel it with every part of my body, doing positive self-talk—‘you can do this’—and it’s just a really quiet, focused moment. I look straight somewhere. I am grateful for every moment up there. I smile before I drop, and then just ski.”

With two Red Bull Cold Rush first place finishes and numerous iF3 Film Fest awards to boot, Sean Pettit, 24, regards the backcountry with remarkable humility. Consider the comparable technique he uses to derail ominous thoughts while standing on a peak: “The best thing I can do personally is not think about it at all. When I think about it, I psych myself out. I will actually look away after I pick my line, turn the opposite direction so I don’t over analyze it. Once I drop, the fear goes away.”

For Angel Collinson, 26, star of Teton Gravity Research films and two-time Freeskiing World Tour Champion, the mountains are sublime. Her preparations are similar to Lahnsteiner’s and Pettit’s, and yet enhanced by the emphasis she puts on gratitude in the process of transitioning to clarity-of-mind just before dropping in: “I get maxed out on nervousness and need to bring myself down a couple notches. I do this with breathing. I mean, like, deep breathing, and taking in all of my surroundings. Appreciation helps me to feel the most present. That’s the most grounding and best thing I can do to get rid of my nervous energy—‘look at this view’—then I give appreciation to Mother Nature for being so awesome. I ask for her blessing of the line I’m about to ski. I like to think of it as a co-creative dance. I also visualize the whole run.” And, like the other skiers I interviewed, Collinson stresses that, “Once you drop, all your nervous energy goes away. It requires your full abilities. It’s very still. Intense.” For pros, cultivating a moment of pure lucidity prior to testing their abilities—looking elsewhere, expressing appreciation, smiling—is vital to the combined serenity and heightened performance that allows for the joyful symbiosis that makes “stomping it” possible.

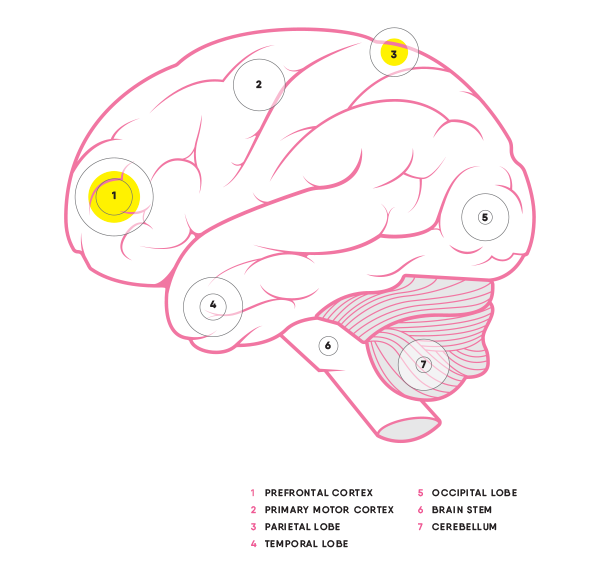

Looking at imagery of people’s brain activity during what they describe as a mystical, transcendent or ecstatic state while meditating, praying or on hallucinogens, Andrew Newberg, et al., determined that, “biology, in some way, compels the spiritual urge.” Newberg observed that the area of the brain (posterior superior parietal lobe) in which activity is high while humans orient themselves in physical spaces and perform motor functions becomes relatively inactive when they achieve the “flow state” while meditating—or through spiritual or other consciousness-altering activities. At the same time, a different part of the brain (prefrontal cortex) which is responsible for combining attention, intention and processing of mind-body activations—often through abstract impressions—becomes hyperactive. Newberg posits that this “allows humans to transcend material existence,” and reveals “the brain’s capacity to make spiritual experiences real.”

Apparently, the brain responds as if it is no longer necessary to orient the body because mind and body together have surpassed spatiotemporal concerns and attained blissful interconnectivity with everything around it. This comprehensive oneness with the environment obviates orientation because the mind-body experiences the physical spaces through which it moves as extension, that is, as contiguous occupation of space. Building off this research, David Yaden, et al., analyzed the kinds of words, such as those expressing “gratitude” and “oneness,” people regularly use to describe such “mystical experiences,” “temporary mental states that include profound feelings of unity,” and “transcendent ecstasy.” He concluded that these types of experiences could be communicated with ordinary language in everyday conversation.

The same words, as I learned from the interviews, such as “flow,” “spiritual,” “clarity,” “still,” “intense,” “high,” “connected” and “everything,” are also commonly used by backcountry mavens to describe the consciousness achieved while shred- ding massive lines. Following Newberg, this suggests a natural motivation to ski big mountains—to go for the transcendent ecstasy that is your reward for accomplishing the goal, and therefore for the step-by-step mental preparation that helps you get there. Thus, we can hypothesize that brain activity in the orientation area similarly diminishes because the skier is feeling at one with the environment and transcendent. They’re both individual and connected, totally aware, fully immersed in the heightened performance.

Beyond his five X Games medals in slopestyle, Sammy Carlson, 27, has brought home three consecutive X Games gold medals for the Real Ski Backcountry video contest. Growing up skiing on Mt. Hood, in Oregon, Carlson uniquely honed both big-mountain and terrain park brilliance. For Carlson, “Once you drop, you’re in the zone, in sync, picking up on things without thinking, you are in the flow state. It’s definitely another level of consciousness. You’re working super fast. It’s a calm, still place.”

Collinson explains the consciousness-altering experience with similar language: “It’s kind of similar to meditating. It’s the flow state, when you drop in and your mind just goes blank and you’re totally focused on what’s in front of you, and you’re not thinking about anything else. I have this sense of peacefulness and clarity.”

“In the flow state,” according to Lahnsteiner, “every-thing is moving in accordance with the moment before and the moment after. You feel connected.” Further corroborating their experiences of heightened performance, Pettit sums up the ecstatic and addictive power of successfully skiing a big-mountain line, noting, “Right before I’m going to drop in I feel unbalanced and nervous, because of that fear, but as soon as you drop in, it’s like a light switch, it’s night and day, it fully changes once moving… it’s a high, you’re highest when you’re energized, you’re invincible. It is so rewarding when you get to the bottom, you want to go back up and do it again.” This brings us back to Newberg, whose research suggests that we can only satisfy our inherent quest for spirituality through “transcendence of the self, and the blending of the self into some larger reality.”

From the world-class backcountry shredders who generously shared their preparations and experiences, we have learned that however we want to up our game, even if just by graduating to slightly bigger lines, drops, jumps or tricks, we should wholly tap into the immense power of our brains to make the impossible possible. From the cutting-edge neuroscientists, we have learned that it is both natural and desirable for us to do this. As Pettit encourages, “Anybody can do what I do, if you have the confidence to do it.” No brain, no gain.