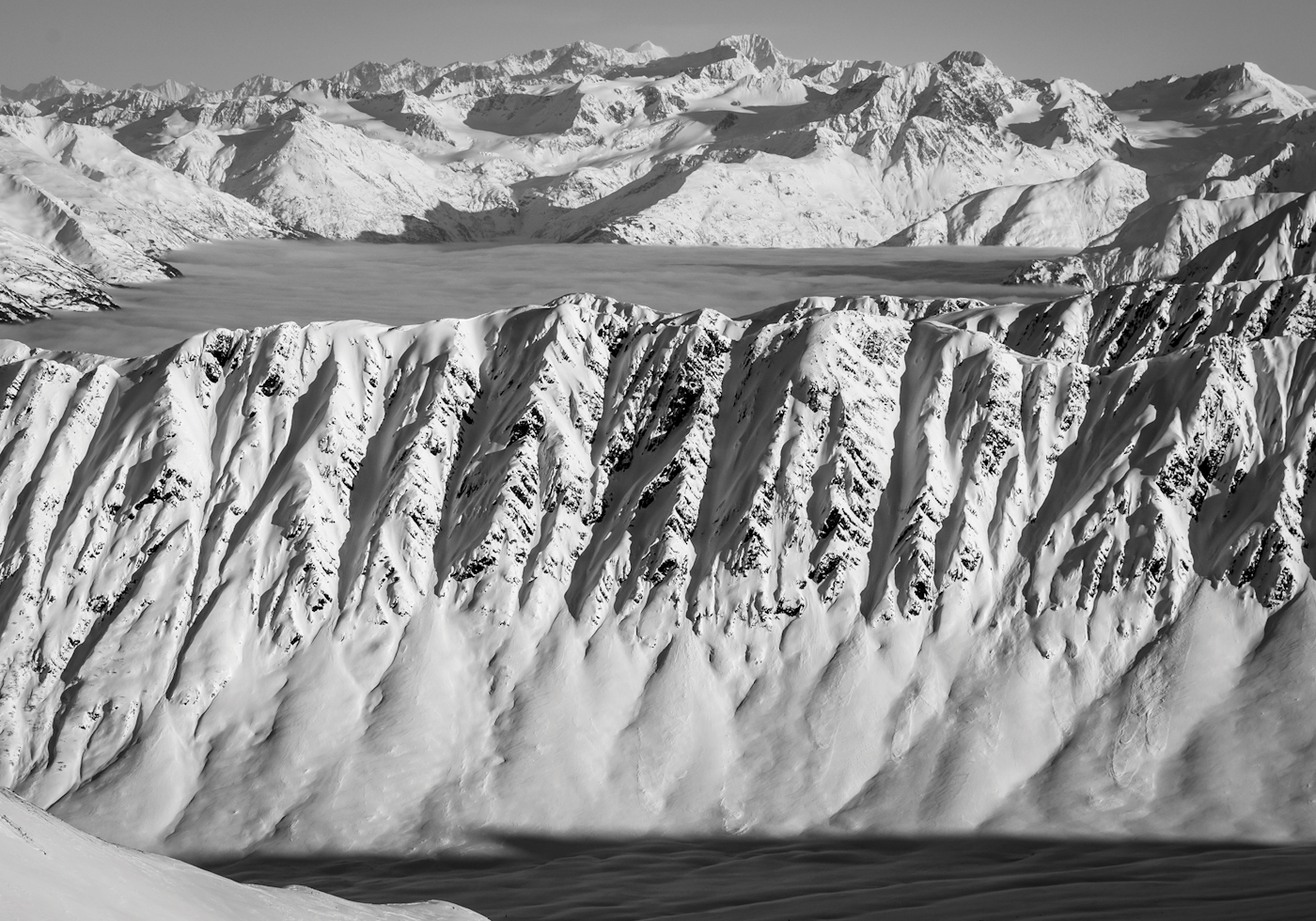

Words ■ Derek Taylor // Photos ■ Carson Meyer

Josh Randich is whacking the vertical wall of snow with his ski pole. He’s just below the summit of Explorer Peak, 3,500 feet above the Portage Valley near Girdwood, Alaska. A steep powder slope drops off to his left, shale rock to the right. Below him Wiley Miller, Scott Rich, Matt Sterbenz and photographer Carson Meyer are stretched out, following his boot pack. This is the final move in the final climb of a six-day backcountry skiing mission around Turnagain Pass. Everyone is exhausted, but the worst of it—a traverse across a 50-degree slope with punchy snow over big exposure—is behind them. This fin hike is just a stroll to the summit… that is, until it dead-ends at this 10-foot cornice.

Randich will laugh about this later. Right now, though, he is in a full-on embrace with the snow, hacking hand- and foot-holds and notching out the top with his Whippet poles—anything to help them scurry to the summit.

Randich is the reason everyone is here. Born in Anchorage, the 27-year-old moved to Girdwood just out of high school. He works on commercial fishing boats all summer. In the winter he skins up ridgelines and punches boot-packs along mountain faces in the southern Alaska backcountry. In 2009 he struck a product-based sponsorship from 4FRNT Skis, and since 2013 Randich has floated yearly invitations to his teammates to come check out his backyard.

Sterbenz, 4FRNT’s founder, is familiar with Girdwood, and understood how rare it was to have an open invitation from Alaska’s low-key and understated backcountry community. He saw an opportunity for an inside look at one of America’s most unique backcountry ski scenes, and didn’t want to see it slip by. “It got to the point where, if we didn’t say yes, I was afraid he was going to stop calling,” Sterbenz says.

Josh Randich, pictured above, is an Anchorage native who works on commercial fishing boats in the summer. In winter, you’ll most likely find the 4FRNT-sponsored athlete seeking out fresh snow in the Girdwood backcountry.

There are two types of Alaska ski trips you read about in ski magazines. There is the heli trip, where skiers hunker in a fishing village or backcountry lodge for weeks on end, “drinking it blue” — waiting for weather windows in which they can safely fly to nearby summits and flash down formidable skiing lines in 15 seconds. And there is the hardcore backcountry camping trip, where adventurers rough it on a remote glacier, digging out tents when it snows and bagging peaks and checking off descents when it’s clear. Both sorts of outings, almost always, come to fruition in the springtime.

This is a different Alaska skiing story, one that takes place in the shadows cast by the North’s long nights, where locals drive old pick-ups to the trailhead, skin and climb for hours to ski film-worthy lines, and return in the dark, speaking hardly a word of what they just accomplished.

In mid-January of 2017, world renowned skier Wiley Miller was skiing powder near his home in Pemberton, British Columbia, when he got a call from Sterbenz. “Conditions were really good [around Permberton]. It was snowing, we were skiing the trees…” Miller remembers. “My initial thoughts were, AK, during the first week of February? Are you sure? I just know Alaska is so dark, and I’ve never really heard of too many people going up there in early February and getting anything done. So, I guess I was hesitant.”

As Sterbenz outlined the details of the trip—that they would be hooking up with a local whom neither had actually met, who would then unselfishly tour them around his home turf—Miller grew more skeptical. “Josh could have been any number of a type of person,” Miller says. “And when you’re out in those conditions you want to trust who you’re with.”

Randich had concerns of his own, but not with his would-be partners. He planned their visit around his favorite stomping grounds: Turnagain Pass. “When they said they were coming up, I knew if we got the right window, this is what I wanted to do,” he recalls. But as the trip approached, Randich began to second guess himself.

“I’ve taken lots of people out to that area, so I was comfortable with the idea of bringing new people, and I knew that they all probably had strong mountain skills,” Randich says. “I was more worried about the quality of riding. Here’s Wiley Miller, who’s been a professional skier for a long time… He’s skied all over the world. So, that’s what I was nervous about, wondering, is this even going to be up to snuff? Are they going to be stoked on it?”

Before he could find out, the conditions needed to line up. “When they called me, where the snowpack was at that point and what the weather had done… we needed three weeks for everything to set up,” Randich says. “It just so happened in those three weeks, everything that needed to happen, happened. It cooled down, it snowed more, everything bonded and had time to heal. They got there on a Wednesday, and that Tuesday was the first blue day we’d seen in a while. Immediately, we were able to go out to these prized zones, and they hadn’t been touched yet. We were the first ones to start opening them up. It was perfect timing.”

Miller arrived late on Tuesday night, and by 7:00 a.m. the next day was on his way to Turnagain Pass via truck. “As we were approaching the trailhead, the sun started hitting the peaks and it was obviously going to be a bluebird day,” Miller says. “We started to see some of the faces…it was ‘all-time ’rolling up that morning.”

Randich tried his best to act nonchalantly. This was the warm-up day—lower consequence terrain with big runouts where they could assess the snowpack and get a feel for each other. For Miller, that meant the first move of his trip was a 15-foot cornice drop straight onto a spine he had only seen from above. He landed, made four turns, went weightless over a wind lip, then slashed the spine a few more times before airing out with classic Miller style near the bottom of the run.

The pair started booting up for another lap; the tone for the trip was set. “I was very gun-shy,” Miller says. “We were going up these big faces and I didn’t know if stuff was going to start sliding on us. Josh seemed super comfortable and was just like a frickin’ goat… he just went up. And I followed him. And that’s how it went the whole trip. He laid the boot pack and I followed.”

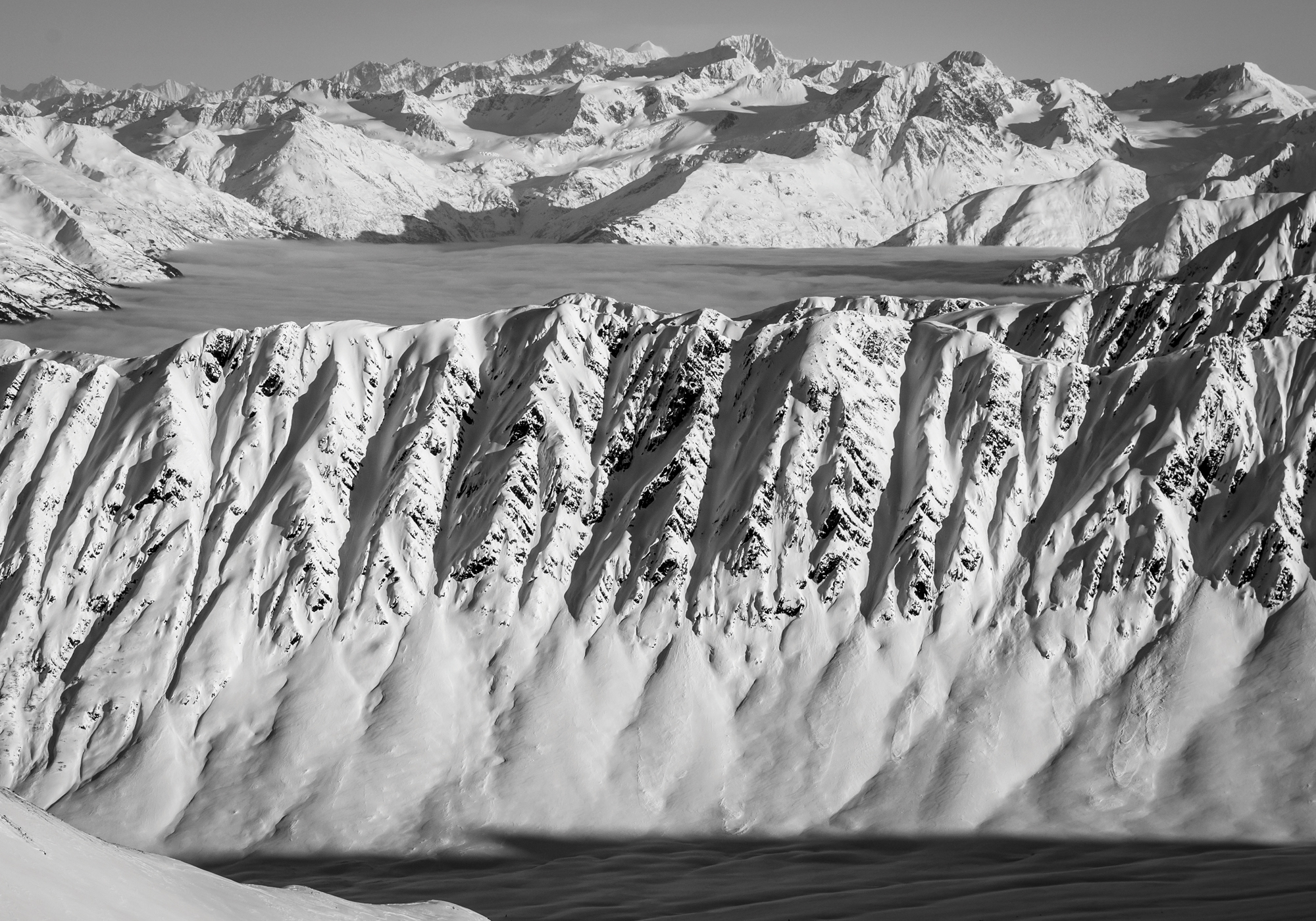

Turnagain Pass is comprised of a series of ridges and canyons. From the top of Gold Pan, Randich lined out the coming objectives, each one a little more committing and requiring a little more work. Day two was spent in a zone called Libraries, which Randich now calls his most fun ski day of the week. “It’s some of the cooler terrain that we got into,” he says. “The lines are just long enough where it feels like a really good ski, but they’re also short enough where you feel comfortable ripping them harder.”

Both runs completed in the Libraries were accessed by skinning out the valley floor (rather than following the ridgeline, like at Gold Pan), with Miller and Randich booting up gullies and skiing spines back down. Randich started his first run with five turns above a 40-foot cliff. He opted for a small air off the side, then linked up with a spine that he surfed to the bottom. They moved down valley, stomped back up the hill and finished their second runs as the setting sun cast dramatic shadows on the wall.

Unlike other well-known Alaska ski locales, which still survive as fishing and freight ports ten months out of the year, Girdwood is a resort town. Where in Haines or Valdez—two of the most trafficked destinations for skiers—you’ll return at the end of the day to a Best Western or a road-side motel, in Girdwood you have the four-star Hotel Alyeska. “It was kind of the yin and the yang,” Miller says. “You’re out all day beating yourself up in the sun and the cold and the wind, and then, boom, right into plush mode… like the exact opposite. [Girdwood] is unique in that regard. You have four-star accommodations and access to relatively uncrowded, somewhat untapped terrain off the pass. I don’t think there are a lot of people that really want to put in the work to get up into those lines. Certainly there are a lot of people in Girdwood who do, but in terms of visiting filmmaking crews…”

For Miller, that effort finally took its toll. “After the second day, I looked at Sterbenz at dinner and was like, ‘I need one day off. I need to chill,’” Miller says. “I don’t think anyone wanted to say it, but we were all feeling that way. And actually the only person who didn’t want the day off was Josh.”

The crew spent a recovery day visiting a homemade sauna tucked into the woods around Girdwood and another cruising the groomers of Alyeska Ski Resort. On day five, they returned to Turnagain Pass, skiing a zone called Eddies. On the way home, Randich asked the crew to pull over.

The sun had disappeared in the valley, but was still illuminating the nearby peaks, lingering the way it so often does during deep winter in Alaska. “Josh pointed up at this mountain,” Miller remembers. “He said he always wanted to go up to this one particular spot, but we hadn’t really considered it.” Randich was singling out Explorer, a peak he’d never skied. But with the crew gelling and the conditions cooperating impeccably, he saw this as his opportunity.

The Portage Valley is a roughly 12-mile stretch of land separating Prince William Sound and the Cook Inlet. It is the narrowest landmass separating the two large bodies of water. “Usually the weather is so bad there, it’s not really favorable as a skiing spot,” Randich says. “There are usually other areas that are skiing better. It just so happened that during this window the winds were really calm and it set up that area really nicely.”

Explorer also had the benefit of a more westerly exposure than the south-facing slopes they had been skiing all week, which had been heating up on account of the high pressure and bright sun. But it brought a whole new set of unknowns. “We all agreed that it would be a lot of work, probably the most vertical that we had to do during the whole trip, in terms of climbing,” Miller says. “The fact that Josh had never been up there created some variables. Maybe we wouldn’t even be able to get on top.”

From the top of the cornice, Randich reaches down and gives Miller a hand up to the summit. Miller then helps do the same for the rest of the crew: Sterbenz, Rich—a friend of Randich’s who had joined for Explorer—and Meyer. From the summit, they look down on Turnagain Arm to one side, Prince William Sound to the other. This is the pinnacle of the weeklong mission; the culmination lies below them. One at a time they drop in for a 3,000-plus-foot descent to the car.

In most of the skiing states in the lower 48 there would be a guide book highlighting this line with a detailed history of who skied it first and when. But this is Alaska.

“What struck me, coming from Utah, where so many people obsessively promote what they just skied, via Instagram or the Utah Avalanche Center observations page…” says Sterbenz, “is we would see people at dinner and ask what they did, and they would say, ‘we went skiing,’ or ‘we went out to the pass.’ It wasn’t until you really got deeper into the conversation that you’d be like, oh, you’re the group we saw out on Wolverine. Sick! We saw so many groups of skiers stepping up to seriously intense climbs and lines. Their comfort level on that size of terrain was absolutely mind-numbing.”

“When I drive around this area, I pretty much just assume that everything has been skied because there are just so many amazing skiers out here,” says Randich. “You never hear about it. Alaska people are more about not getting recognition and doing things under the radar.”

And yet is was Randich who invited this crew to his home, who allowed them to document his playground in a four-part video series, hitting freeskier. com in the fall of ‘17. “I don’t think I’m giving away too many secrets,” he laughs. “Everything we skied you can see from the road. These are the gimmies.”

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Limited Edition FREESKIER Hat](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1772568976-3x4a9169.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)