WORDS • MEGAN MICHELSON

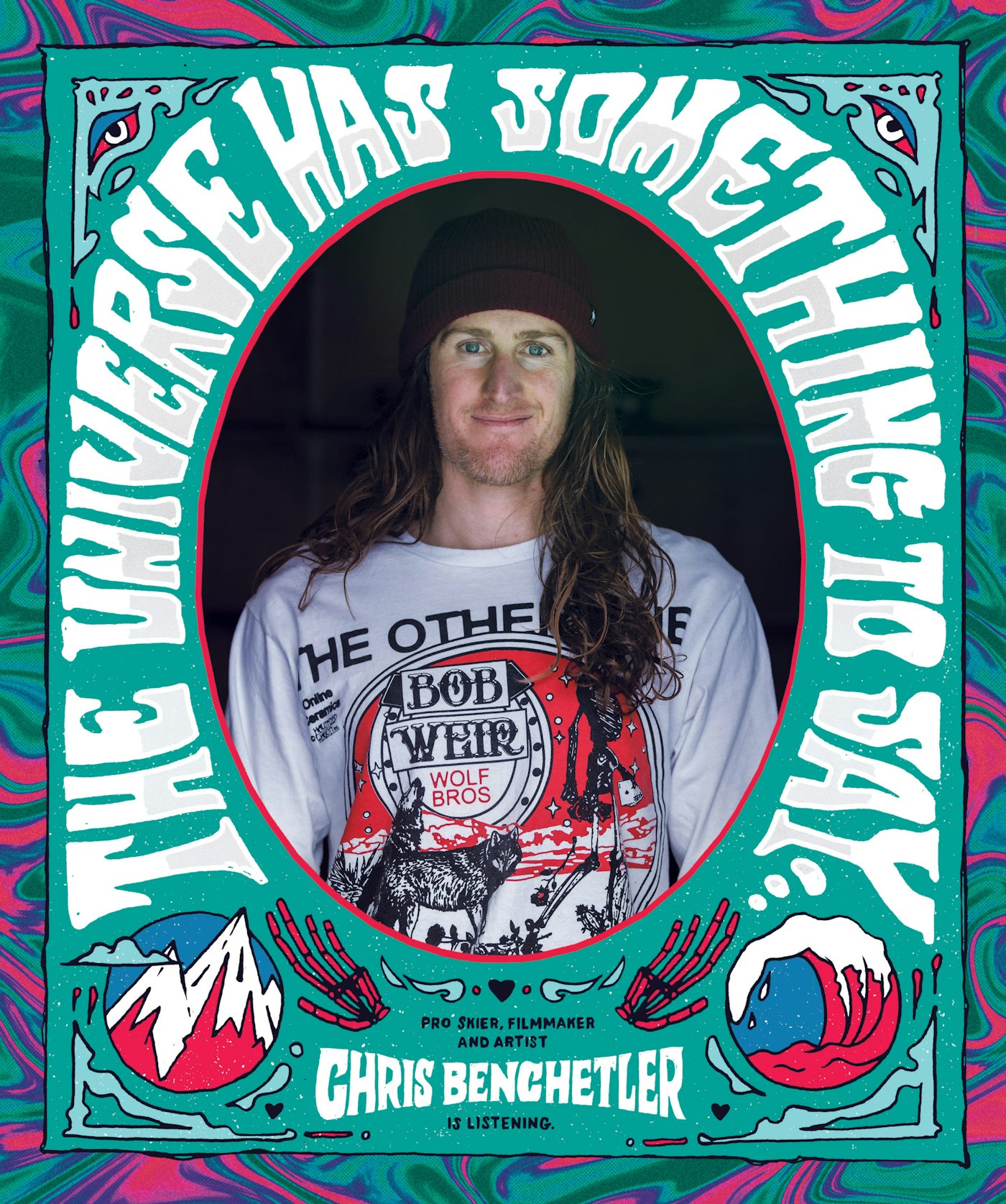

It’s March 2018, and a storm is pounding the upper mountain, which is shut down due to hurricane-like winds. By 2 p.m., the fair-weather skiers have retreated indoors to saddle up to the bar. Not me. And certainly not Chris Benchetler, who I bump into on Mammoth Mountain’s Chair 22, a creaky old triple in a wind-protected corridor that is somehow still running despite the monsoon. Benchetler is stealthily dressed in all black, but he’s easy to spot, even in poor visibility, thanks to his all-white prototype pro-model Atomic skis and, of course, his easy-going, high-speed style through the trees.

We ride the chair together and catch up. His wife, pro snowboarder Kimmy Fasani, is due with their first child any minute now. “I have this feeling the baby is coming tomorrow,” Benchetler says. The next day is a full moon, he tells me, and it’s also the date that his dad died, 15 years prior. Benchetler is the kind of guy who gets those kinds of feelings, about the universe and what it’s telling us.

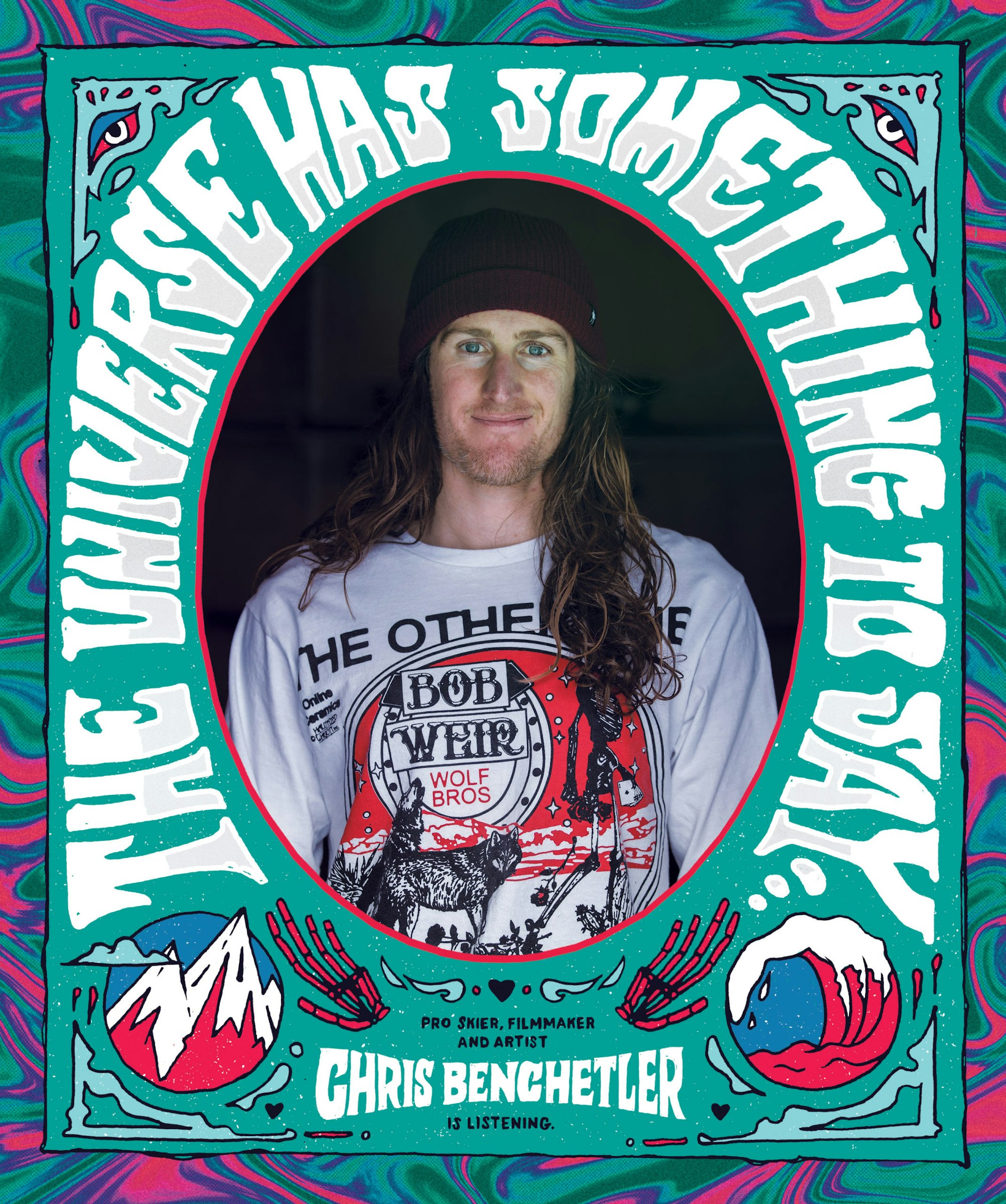

P_Oskar Enander | L_Rusutsu, JPN

At the top, he says, “Follow me,” so I hustle to keep up. He leads me into a zone with steep rock walls and untouched, knee-deep powder. It is paradise. Benchetler flashes it and disappears into the squall.

One day later, as predicted, their son, Koa, is born on the tail end of the storm under a brimming full moon.

I visit Benchetler at his home in Mammoth Lakes, California, a year later, in March of 2019. Koa has just turned one and he’s crawling around the floor in search of who knows what. When he starts to squawk, Benchetler picks him up and points to things in the kitchen, saying, “That’s garlic. That’s a banana, an avocado, those are wind chimes.”

Certainly, their lives have changed since they had a child but not drastically. Six weeks after Koa was born, Benchetler and Fasani carried him to the base of crags in the eastern Sierra so they could climb. When he was five months old, the family loaded into an RV in New Zealand for a month, skiing, snowboarding and surfing. They spent two weeks in Japan last winter, filming and eating noodle soup and finding endless powder around Hokkaido, all with Koa in tow. In May, when Koa was 14 months old and had just learned to walk, Fasani and Benchetler took him on a sailboat in the fjords of Norway for a week, where they took turns climbing couloirs and watching their son. One of Koa’s first words was “van,” which he says while pointing to their custom-built Mercedes-Benz Sprinter. Koa has even had his first Grateful Dead experience already, attending a Dead & Company gig at the Gorge Amphitheater in Washington this past summer.

Benchetler, Kimmy Fasani and their son, Koa, prepare for a tour in Rusutsu, Japan. | P_Oskar Enander

That’s especially fitting given Benchetler’s latest project: a 30-minute action sports film, called Fire on the Mountain, set to a Grateful Dead soundtrack that debuted in New York City in November. The film stars Benchetler, Fasani, plus heroes like skier Michelle Parker, surfer Rob Machado and snowboarder Jeremy Jones. It’s a ski, snowboard and surf film, but it’s also way bigger than that. It’s a movie about music’s impact on art and life. “I’m not hanging my hat on this project,” Benchetler says. “But I wanted something to pour all of my energy into.”

“Why the Grateful Dead,” I ask? “The band and vibe are based on improvisation,” he says. “I relate that to skiing and surfing and snowboarding. You never ride the same line twice. You can have your toolbox of skillsets you’ve acquired over a lifetime, but you’ll never repeat the same thing. That’s the allure of the Dead—you’ll hear the same song, but they’ll never play it the same way twice.”

Benchetler, 33, wasn’t always a Dead fan. He grew up listening to classic rock with his dad. But a number of years ago, a friend introduced him to the band and he was mesmerized. When representatives from the Grateful Dead went looking for a ski collaboration, they reached out to Teton Gravity Research (TGR) co-founder Todd Jones to see if he knew any athletes who’d be a good fit. He drew a blank at first, then he showed up at Benchetler’s house, where the Dead album American Beauty was playing on the record player, alongside a wall of guitars. Benchetler would play the Dead song “Ripple” to put Koa to sleep at night. It was a sign from the universe.

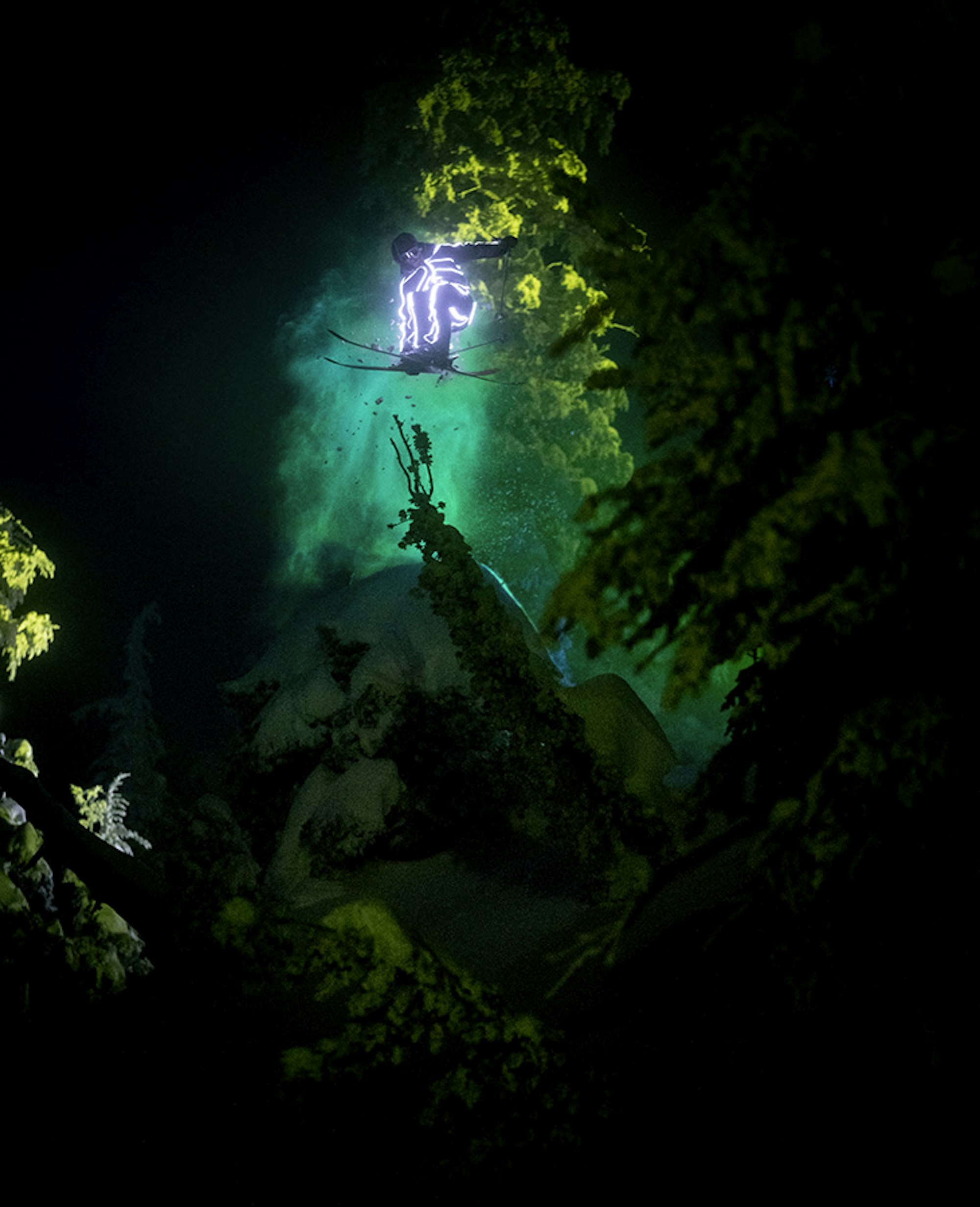

Since then, Benchetler’s been on a Dead bender. Mammoth Mountain closed down a section of the ski area for his film last winter so TGR videographers could shoot Michelle Parker, Jeremy Jones, Danny Davis, Fasani and himself shredding at night, decked out in LED suits. He’s designed custom, limited-edition Grateful Dead gear, including Atomic Skis and a Dakine pack and gloves, and he’s working on making the artwork for a new Dead vinyl box set. “When I get attached to a concept or idea, I have a serious problem of getting overly attached. I have that mentality,” Benchetler says. “It’s been escalating and evolving way beyond anything I ever hoped. At the same time, I’ve never been so busy and stressed in my whole life.”

P_ Aaron Blatt | L_ Mammoth Mountain, CA

For many years, Benchetler was just a pro skier, a decorated and creative one, sure, but simply a skier. Now? He’s an artist, a producer, a dad. Most importantly, he’s himself. “My biggest achievement? The fact that I’ve pursued this life,” Benchetler says. “I’ve figured out how to make a job out of this. It’s all an extension of me.”

Benchetler got his first free pair of skis after a slopestyle competition around the same time his dad was diagnosed with lung cancer. He was 14. His dad died two years later and Benchetler, who was raised near Mammoth Mountain in the eastern Sierra town of Bishop, was forced to grow up quickly after that. “I know skiing felt like an escape, but still, I tend to wear my emotions on my sleeve,” he says.

Slopestyle competitions distracted him, but he was never all that good at them. He’d always choke in finals. “I never had that desire to beat everyone else,” he says. “I had an extreme drive, but it was always within myself.”

P_Aaron Blatt | L_Mammoth Mountain, CA

When Johnny Decesare, founder of Poor Boyz Productions, asked Benchetler, then still a teenager, to appear in one of his movies, a new world cracked open.—both personally and professionally. He had an evening job at an ice cream parlor in Mammoth, so he could ski and film all day. One day, a snowboarder named Kimmy Fasani walked in for ice cream and the two got to chatting. Her dad had died of lung cancer a few years earlier, and they bonded over the shared grief. She was 19; Chris was 16. “We’d both been through loss and because we were able to have that bond, it elevated our relationship,” Fasani says now. They’ve basically been together ever since.

Benchetler dominated ski movies after that, from Poor Boyz to TGR. But in 2007, he got together with friends and fellow pro skiers Eric Pollard, Pep Fujas and Andy Mahre to create Nimbus Independent, a production company that started putting out web videos long before webisodes were a thing. “Chris and I would end up with parts in these bigger ski films that were maybe not what we would have created on our own. We wanted to work together to create something we believed in,” says Pollard. “We came from the very traditional movie release and we thought, let’s turn that on end. It sounds outdated now, but at that point, it was a new format. Nobody was releasing their own videos online.”

Nimbus generated a cult following—their short, travel-centric films were known for their creative and artistic approach. Benchetler got more interested in art along the way. Even back in high school, he was always doodling designs on his homework. So, when he signed with Atomic Skis in 2007 and put out his first pro model ski, called the Bent Chetler, the following year, it was only natural that he’d create the artwork for the ski’s topsheet. That first year, he made a design inspired by a Tokyo subway map, with a tie-dyed woolly mammoth surfing a wave on the tails. “Chris pulled inspiration from a lot of different parts of his life,” says Jake Strassburger, Atomic’s U.S. alpine commercial manager. “It wasn’t him sitting down with a pen and paper and creating artwork. It was him coming up with a way to express himself on a topsheet.”

The 123-millimeter-underfoot ski looked electric, and it floated through powder like a snowboard. His pro model ski, which is now in its 11th rendition and also comes in a narrower 100-millimeter-waisted option, is not Atomic’s highest-grossing or most-sold ski, but, according to Strassburger, it’s the ski they make every year that sells out. “With that ski, I’m expressing myself as a skier and artist,” Benchetler says. “The fact that people can relate to that and want to take part in that is humbling.”

P_Peter Morning

Benchetler’s skiing got more creative over the years, too—more akin to surfing or snowboarding in its playfulness. “He obviously skis at the next level, but Chris is not looking to win a freeride comp or win movie of the year,” says Strassburger. “He’s just happy to see projects through and be creative. He wants to be able to enjoy the mountain. He always seems almost surprised that everyone likes what he does.”

Benchetler doesn’t call himself a religious man, but spirituality is important to him. He aims to feel connected to his surroundings, whether he’s flying down a mountain or playing with his son. “You evolve as a human being. The more I question our existence, there’s just so much knowledge out there, so much indescribable magic,” Benchetler says. “It’s just an incredible place where we live. I’m experimenting, I’m soul searching, I’m trying meditation. I try to be a very present father, to live as present as possible.”

His work as an artist has also evolved. “Art is hard to label,” Benchetler says. “I’m down to create. I’m interested in dabbling. It’s also super meditative for me, and I’m just learning how to utilize that.” He started painting large-scale murals using spray paint and acrylics, and his talents attracted other brands in the ski industry to commission him to design art for gloves, shirts or packs. “I’m an unfortunate ‘yes man,’” Benchetler says. “I just can’t say no.”

As Pollard puts it, “Chris is good at taking opportunities. He goes all in. He’s a very ambitious guy.”

By 2015, Nimbus was starting to fade. Benchetler knew he needed to venture out on his own if he wanted to keep producing content. “When Nimbus started to fizzle out, I was like, ‘what am I going to do?’ I can’t just go back to ski movies. I had to take ownership of my career,” he says. So, he bought and tricked out a van, which he named the Stealthy Marmot, complete with its own custom mural he created, and he took to the open road, documenting his travels. He made a four-part video series with GoPro called Chasing El Niño in 2016, and a 30-minute short called Chasing AdVANture in 2017 that showcased Benchetler visiting the surfers, artists, snowboarders and climbers who inspire his skiing.

The Grateful Dead film became his next major project, the single focus that would take over his world and also draw brilliance from it. Now that the film is out and touring alongside an interactive art display, what will the universe bring Benchetler next? Since Koa was born, Benchetler has been slowly at work on a family-centric film, capturing their globe-trotting adventures as a unit of three. It’s still a work in progress, since Koa has a lot of growing and learning left to do. So does his dad—he’ll take his cues from the universe.

Gear Spotlight

Atomic Bent Chetler 120 – Buy Now

Chris Benchetler’s wings to fly through fields of fresh, the Bent Chetler 120s are the ticket to powder heaven. HRZN Tech in the tip and tail–a horizontal ABS convexity–accounts for its incomparable flotation and playfulness as well as its ability to deflect variable snow. The folk-music-infused topsheet art designed by Benchetler himself will assist you in dancin’ through the daylight.

Dakine Benchetler Grateful Dead Team Baron Gore-Tex Mitten – Buy Now

Chris Benchetler’s wings to fly through fields of fresh, the Bent Chetler 120s are the ticket to powder heaven. HRZN Tech in the tip and tail–a horizontal ABS convexity–accounts for its incomparable flotation and playfulness as well as its ability to deflect variable snow. The folk-music-infused topsheet art designed by Benchetler himself will assist you in dancin’ through the daylight.

This story originally appeared in FREESKIER 22.3, The Backcountry Issue.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a 4-Night Karma Campervan Rental and go Ski the Powder Highway](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1767816935-copy-of-dji_0608-1.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Legendary Ski Trip with Icelantic's Road to the Rocks](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1751532112-rttr_feat.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)