Skiing’s benevolence emerges in the land of fire and ice

WORDS • DONNY O’NEILL | PHOTOS • ADAM KLINGETEG *unless otherwise noted

The gray-haired Russian woman in the window seat tapped me on the shoulder.

There must be a lot, as this is the first she’s acknowledged my presence in the eight-plus hour flight that preceded this interaction. I leaned forward, gave a nod to her bear of a husband in the middle seat and looked out.

I’d gazed at photos prior to the trip, naturally, but even as we descended toward the peninsula, 30-plus hours into my voyage around the world, I was unsure what to expect coming into my final destination. Russian relations with the United States certainly caused internal trepidation to travel anywhere in the world’s biggest country. From everything I’d been told, though, this wasn’t remotely like western Russia.

William Larsson puts on a show in front of a Kamchatka geyser.

Out the window, it was white: A ghostly sheet extended as far as the eye could see. Past the wing stood Avachinsky, an 8,993-foot active stratovolcano adorned in its winter coat. I wiped the disbelief and wearisome travel from my eyes and sat back against my seat. The Aeroflot attendant’s voice came over the speakers and conveyed in Russian what I assumed was the announcement of our final descent.

I glanced once more at the foreboding leviathan framed in the window as the attendant confirmed my suspicions in English. Soon after, we touched down in a land where the opposing elements of fire and ice collide: Kamchatka.

Fischer Skis invited me, ski shop representatives from Washington, Switzerland and Austria and one other media member here, to the far northeastern peninsula of Russia. What was originally billed as a product test in a mostly unheard of, faraway land, soon presented itself as so much more.

Kamchatka has always been defined by its remote location. It’s been a deterrent of human traffic since before the first Russian explorers set foot there in the late 1690s. The peninsula remained more-or-less a mystery throughout its early settlement, with native rebellions and wars marking the first fifty or so years of its recorded history. In fact, other than one published description, An Account of the Land of Kamchatka, in 1755, a coordinated British and French attack on its shores amidst the Crimean War in 1854 and a Confederate sail-by of the southern coast during the American Civil War, the history book of Kamchatka as read by the Western world was thin through the second World War.

The Soviets made Kamchatka a military zone during the Cold War, and it remained closed to the public, including Soviet citizens, until 1989, which further shrouded the spade-shaped peninsula in mystery. Foreign visitors were allowed to travel there beginning in 1990, but even after nearly thirty years, the Kamchatka Peninsula remains unknown to the vast majority of the world. For those aware, it was likely in reference to the growing fly-fishing industry developing in the summer months, or from the few images of surfers who voyaged there to ride its hostile waves. Travis Rice, the snowboarder, came here once. The story of skiing in Kamchatka, however, is still unfolding.

Our first minutes in Petropavlov-Kamchatsky, the arrival city, capital and population hub of Kamchatka, were spent nervously awaiting the emergence of our luggage in a narrow building near the runway. One by one, our multi-national crew lugged ski bags and suitcases outside with a sense of relief and congregated around two of our Fischer hosts, Alex and Jan.

The two Austrians welcomed us and conducted introductions. Jan Weiss is the head of the alpine division for Fischer Sports in Innkreis, Austria, while Alexander Schachner works as the general director of Fischer Russia, based in Moscow. According to Schachner, a storm—brutal by the very nature of our location—was forecasted to roll in that evening, and time was of the essence. We were escorted to our bus, its interior strung up with dangling decorative tassels that radiated a rather royal atmosphere in an otherwise dated vehicle. Alexander and Jan distributed liter bottles filled with beer, foreshadowing a staple of our diet for the next week on the peninsula.

The bus carried us through the outskirts of town, where a cold, gray, distinctly Soviet atmosphere pervaded. Inside the bus, our group of 14 naturally split into language-driven cliques. Pro skier William Larsson and photographer Adam Klingeteg traveled here from Sweden, and the two Swedes were inseparable from the moment we stepped on the bus to the day we departed the peninsula. Then, there was Beat, Séb, Fred and Jvan, the gregarious dealers from Switzerland. Scratch that, Seb was very quiet, but could arch a telemark turn that was anything but. Viktor Maigourov, a former Russian Olympic athlete, knew Weiss and Schachner well, and Fischer representatives Jessica Wiederhold and Mike Hattrup were getting acquainted. That left the Americans: me, Gear Patrol’s Tanner Bowden and Pat Mahoney from evo.

Hand plants across the North Pacific. Skier: William Larsson

As is natural with any travel existing outside the comfort zone, our group segregation would soon be shattered by the common experience. The bus brought us to a private landing strip, and there, just beyond the entrance gates, sat a giant orange helicopter, an ex-military Mi-8. Three men, dressed in what, from afar, appeared to be extra large starter jackets from the ‘90s, loaded various supplies into its rear chamber. A huge Fischer logo adorned the Mi-8’s exterior—this must be our ride.

We trotted out onto the runway, swiftly, at the gruff instruction of our hosts, and our luggage was tossed into the bird’s rear. We piled inside via a large door on the helicopter‘s side and were forced to contort our bodies into our seats to accommodate the five giant blue cans of gas that took up the interior’s center aisle. In a blur of shuffling feet, our team successfully crammed into the chopper. Our pilots positioned themselves up front, muttered to each other in Russian, flicked switches and pushed buttons. The low, guttural growl of the engine slowly picked up volume and the blades began to rotate above us. A soft swishing emanated first, but soon, it evolved into a thundering wump! wump! wump! that drowned out any other audible sounds. The warbird shook and rattled, and before long, hovered slightly above the ground. In a single burst, the mechanical beast lurched into the sky, sent our stomachs into our throats and accelerated south toward camp.

We flew low and followed the contours of the river valley that separated the hills from one another. The ride couldn’t have been more than 20 minutes, but for those who managed to maneuver their heads around to catch a view out the windows, time stood still. The raw, rugged landscape unfolded before us like a pop-up book, and we soared up its gutter toward hulking volcanoes painted white by the artistry of winter.

William Larsson keeping occupied at camp.

The Kamchatka Peninsula is home to over 160 volcanoes. Twenty-nine remain active and are part of the Volcanoes of Kamchatka, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The group includes Klyuchevskaya Sopka, the largest active volcano in the Northern Hemisphere at 15,584 feet tall, and Vilyuchik, the 7,150-foot stratovolcano that presides over Camp Rodnikovaya, our home for the week.

“Kamchatka is one of the most beautiful places on the planet,” Viktor described. “In one place, volcanoes, snow, the ocean, bears, fishing and freeride skiing are collected. There are no restrictions, no limits.”

We touched down in a clearing and de-boarded. Camp Rodnikovaya stood before us. On a swath of land the size of a football field, a collection of refurbished shipping containers, interconnected by wooden walkways and sets of PVC pipe-railing stairs, served as our neighborhood. The shipping containers varied in size and were positioned on a sloped hill so that our backcountry village was elevated to three stories. There was even an old helicopter-turned-dormitory placed at the edge of the compound.

The introduction to our quarters wasn’t an extended one, as many tasks needed completion before nightfall. This wasn’t your typical posh skiing vacation, after all. This was Kamchatka, nothing comes easy here.

We were introduced to one of our gracious hosts for the week, Llena. The grandmotherly figure, along with her underlings Olga and Nina, cooked for us in the main cabin and was the backbone of the entire operation at Rodnikovaya. We unloaded toddler-sized sacks of potatoes, onions and carrots into the cold pantry in the back of the main house, located at the bottom of the container village. Twenty-pound salmon, slabs of venison and hunks of squid were buried outside beneath the snow, while enough beer, champagne and, of course, vodka was stashed in the frozen exterior to inebriate a community far larger than ours. So began our rudimentary crash course on the Russian language, and our subsequent butchering of its pronunciation. Beer, in Russian is pivo, which we pronounced, “beeva”; champagne, shampanskoye, “champanski”; vodka, vodka, “wodka.” We’d get the hang of it, slowly but surely.

Chores done, we swapped our well-worn travel attire for bathing suits and made the bone-chattering walk from our individual rooms to the pool (basseyn, “baseen”). The entire camp utilized thermally-warmed fresh water from the surrounding volcanoes to heat cooking water, our shipping container dormitories and, of course, the basseyn. This allowed for a pleasant water source in which to wash each day and the closest option to an après hot tub scene as you’d find in the middle of this lost wilderness.

We spent the next hour enjoying the restorative effects of the thermal waters, while our world sat frozen around us. The sun dipped in the sky and cast a deep purple hue onto the lower flanks of Vilyuchik. Dinner was at 7:30, and at 7:00 I made the chilling exit from the basseyn and dried off in my room. Warm once again in a sweatshirt, lounge pants and wool socks, I laid down, closed my eyes and finally soaked in my current global positioning after a whirlwind 32 hours of travel to get there.

When my eyes fluttered open, it was the middle of the night. Whoops. All that champanski I drank at the basseyn was holding court in my bladder. I swung out of bed, got into my slippers and affixed my headlamp. Taking care not to disturb my snoozing roommate, I opened the door outside.

I was met with a ferocious blast of icy wind that instantly shook the drowsy from my eyes. I propped myself outside against the container’s exterior wall. The snow flew sideways across the compound and the wind howled with a ferocity that could only be possible in this remote place on Earth. I turned off the faucet, stumbled back inside and crawled into bed. “Kamchatka doesn’t waste any time,” I thought, and drifted back to sleep.

1. Skiing 2. Main Cabin 3. The Swedes’ Quarters 4. Bathroom 5. Dormitories 6. Basseyn

White. The colorless shade made up the entirety of the exterior view from the dining table. Snow pellets flew sideways, a sheet of clouds hung low over camp and the four-foot snow bank grew steadily. All of it was white.

My early exit to bed led to an early arrival at breakfast, and I sat alone at 8:00 a.m. while Llena made the final meal preparations. One by one, she brought out plates of breads, cured meats, cheeses, salmon slabs and roe. She pointed at a mug and asked if I’d like some coffee (kofe, “cofay”). I nodded, still reluctant of attempts at verbal communication considering the barrier.

“Porridge?” she asked and picked up my bowl from the table.

“A little,” I responded, and made the symbol for small with my thumb and pointer finger.

“Ah, chut chut,” she said and mimicked my signal.

I understood, smiled and nodded, “chut chut, a little.”

Each of us would form a special bond with Llena over our week at Rodnikovaya. If it wasn’t for the bubbling thermal waters as evidence, I’d swear it was Llena pumping warmth into the main cabin. Whatever language barrier existed for each of us was torn down by her hospitality in a truly inhospitable place. Her domain was an incubator for connection, and surely contributed to the relationships our group of strangers formed in our brief time at camp.

The others rolled into the main cabin at 8:30, in what was my first introduction to “Kamchatka time.” With the exception of our swift exit from Petrapovlov-Kamchatsky, our trip was marked by a blasé attitude toward the restraints of time. If breakfast was at 8 a.m., it was customary to add an “ish” to the 8 and show up at your leisure.

The storm raged outside, and wouldn’t let up for another 30 hours. Heli-skiing was out of the question, but the gentle knoll above Rodnikovaya offered up exquisite tree runs. The plan was to gather for some group touring at 11:00 a.m., Kamchatka time, of course.

We skinned up the looker’s right of the knoll, then dipped and dodged the wind-twisted family of birch trees strewn about its eastern slopes. The wind howled and formed knee-deep drifts that accompanied the spring Styrofoam that resided there prior. Each descent down the knoll was a grab-bag of dreamy powder turns and stop-you-in-your-tracks encounters with rotten mank. It didn’t matter, though; we were scoring storm laps at the edge of the world.

Our storm activity-cycle consisted of touring, meals, basseyn soaks, vodka toasts (Na Zdorov’ye, “Nostrovia”) and sleep, in an ever-revolving order.

Amidst the cycle, our group of multilingual village inhabitants, who hailed from America, Switzerland, Sweden, Austria and Russia, got to know one another.

Photographer Adam Klingeteg and pro skier William Larsson, the Swedes, were always together and both very outgoing, always quick to tell a joke or light up the room with a smile. They were an active duo, jumping at the chance to head out and shoot, day or night, stormy or clear. The legendary Mike Hattrup, of Blizzard of Ahhh’s fame, among other accolades earned over the course of thirty-plus years in the ski industry, was there representing Fischer. Hattrup, we’d soon learn, was in impeccable shape, and consistently led our ski tours around Rodnikovaya, setting skin tracks and taking the brunt of the work. The Swiss guys liked to party and weren’t afraid to rib us Americans following any boisterous statement we may have made. There was the stoic Maigourov, a former biathlete who won bronze for Russia at both the Nagano and Salt Lake City Winter Olympics. Maigourov had been to Rodnikovaya many times and formed a strong bond with the camp’s owner, Vladimir Shevtsov.

The quiet landlord joined us briefly for breakfast and intermittently during our stay. In his formative years, Vladimir had been a mountain guide for the Soviet Union, climbed all the 7,000-meter peaks in the defunct empire and was a pioneer of heli-skiing in Kamchatka.

Viktor first met Vladimir in April 2005, when a friend invited him to Rodnikovaya, and has visited him in Kamchatka every year since. In addition to the wilderness, it’s Vladimir’s character that draws him back. “I like this place, the nature of Kamchatka,” he said. “And of course, I like Vladimir, as a person, his life principles.”

Injury barred him from joining us on skis, but Vladimir and his operation embodied what skiing in Kamchatka was all about.

“He simply loves ‘his’ Kamchatka and he loves most to show ‘his’ Kamchatka to others, especially to foreigners,” Alexander explained to me. “He was extremely happy to have all of us at his camp.”

When the sun finally broke, Alexander, Viktor, Tanner, Pat and I toured up high into one of the crannies on the lower flanks of Vilyuchik late in the afternoon. The wind made conversation impossible, but our non-verbals conveyed what words didn’t need to. At dusk, we clicked in and skied 2,000 feet of snow-drenched in that magical purple hue, straight to the dinner table, an experience we silently reveled in over venison and mashed potatoes.

Our lone guide, skiing into Mutnovsky. Photo: Matt Berkowitz

The heli-ski pilots arrived overnight and bunked upstairs in the main cabin. They didn’t talk much. After a travel delay, Fischer’s Matt Berkowitz and team athlete Kyle Smaine had also just arrived. We piled into the heavyweight military flier turned powder chariot at 11:30 a.m., with little to no idea of what to expect from our first heli-assisted turns. Vladimir Junior, the heir of the Rodnikovaya throne, and Alexei, a hired guide from another Kamchatka heli-operation, Snow Valley, led our exploration into the ring of fire.

At first glance, the Mi-8 chopper appeared clunky and uncoordinated, but our pilot revealed the true grace and beauty this mechanical beast possessed. Like a ballerina on tip-toe, our bird balanced mightily on ridgelines barely big enough for our group of 14. We took turns getting thrown out of the Mi-8 by one of the burly crew that arrived the night prior. No posh powder landings, here, only hard, knee-buckling ice. It’s foolish to entertain those luxuries way out in these parts. These heli-skiing guides and operators are cowboys, transporting eager powder hounds to volcano tops in a faraway land that’s only allowed public visitors for 28 years. Gentle isn’t part of the makeup.

This was uncharted territory for us civilian cowpoke. For Vladimir, his son and the pilots, this was home, and they knew it like the back of their hands. All we could do was sit back and hold on as they transported us to ski lines that even the boundaries of our own imagination couldn’t have entertained. We teamed up for figure eights down pristine powder bowls and skied past geysers propelling scorching mineral water a hundred feet high. They took us to corn-filled couloirs and duned slopes that led us right down to the waters of the North Pacific. One evening we skied until 9:00 p.m., sharing turns, laughs and fist bumps together on sparkling, golden-washed volcano flanks as the sun bid the edge of the world adieu. The next day, we descended into the belly of an active volcano, Mutnovsky. We gagged on the fumes emanating from an alien landscape and looked back at the ramp of creamy snow that led to the gurgling, oozing crater where we stood. The land of fire and ice, indeed.

Kyle Smaine tours toward Vilyuchinsky Pass on the last day in Kamchatka. Photo: Matt Berkowitz

Featured Gear:

Fischer Ranger Free 130 — $799

Offering a lightweight and ultra-responsive Grilamid construction, the Fischer Ranger Free 130 is any serious backcountry skier’s dream boot. Boasting a 55-degree range of motion when in walk mode, GripWalk soles for increased traction on variable terrain and a heat-moldable inner lining, this ski boot seamlessly combines alpine performance, backcountry prowess and supreme comfort.

Featured Gear:

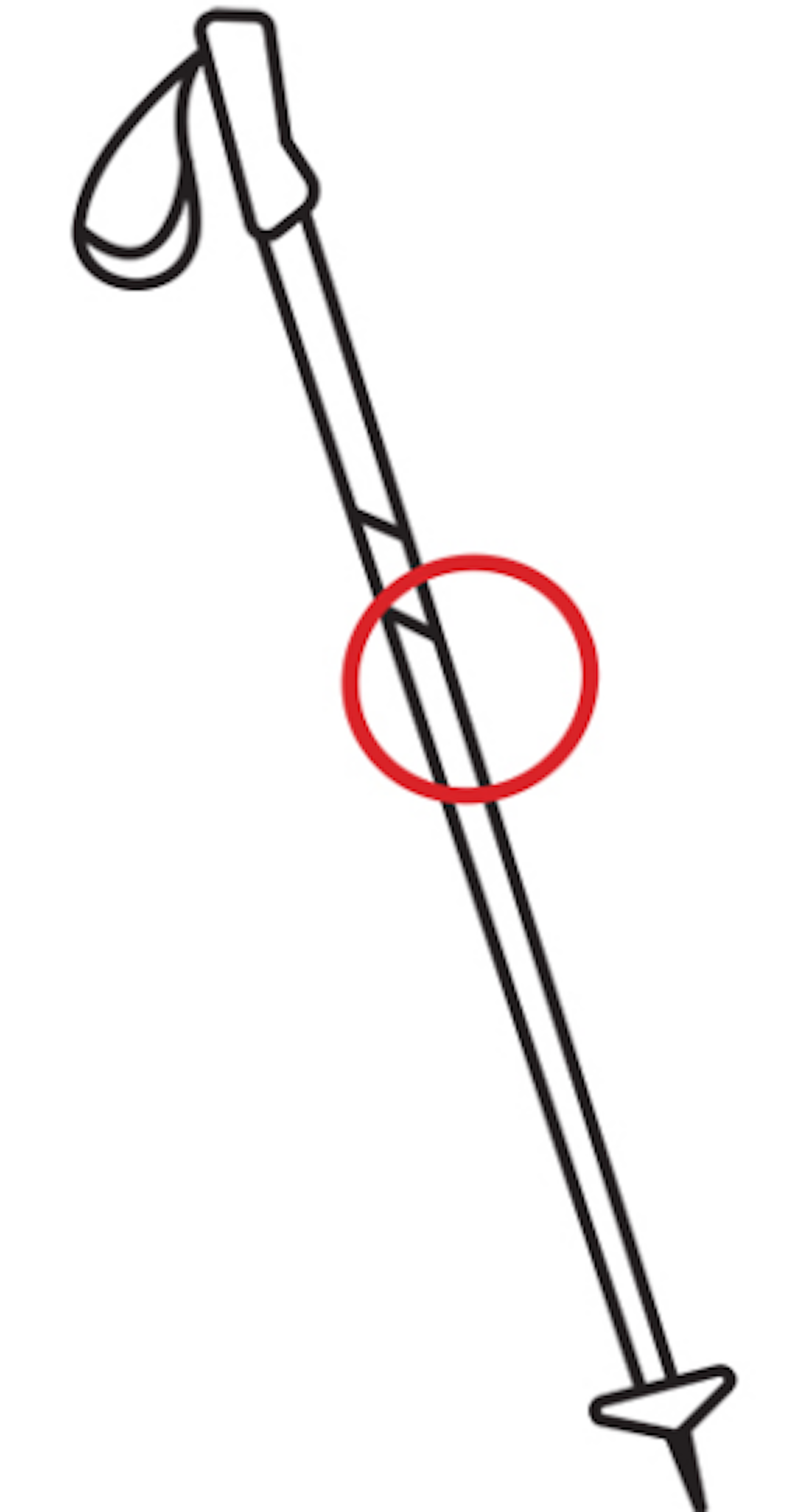

Leki Aergonlite 2 Vertical — $129.95

The Aergonlite 2 Vertical from LEKI is your one-quiver pole. High-tensile strength aluminum keeps this two-part touring pole ultra-lightweight and strong while the Trigger S Vertical grip ensures you’ll never lose these babies on your next line. The TÜV-certified Speed Lock 2 adjustment system makes for quick length changes and the oversized basket will aid you in your deepest descents.

We departed on April 12, seven days after our arrival and just a handful of hours removed from one final celebratory vodka-binge—to Kamchatka! To volcanoes! To skiing! In a manner truly fitting our trip, our only way out of camp was on skis, the very vehicle that brought us together. After a departing snack of fresh caught Arctic char, we toured the 3,000 feet from Rodnikovaya up to Vilyuchinsky Pass.

“We say, ‘Skiing is not a lifestyle, it’s life,’” said Alexander. “Leaving the camp on our skis, and not via helicopter, underscored this. We all traveled to Kamchatka to follow our passion. Skiing brought us together and left us with unforgettable memories.”

At the top of the pass, we put away our skins and glanced back at our Kamchatka home before enjoying a final run together. We descended all at once, collectively weaving and enjoying a few last powder turns through the birch trees. Our skis halted at a snow-packed road, where a Ural off-road truck awaited to whisk us away. With the wilderness at our backs, we climbed in and rumbled toward civilization.

Our group stopped overnight in a hotel outside Petropavlov-Kamchatsky and partook in a customary last soak in the property’s basseyn before retiring. I was the first to breakfast the next morning, where the hotel’s nefarious-looking security officer stood at attention. He’d been there at check-in the night prior and made sure we knew which parts of the hotel were off-limits. The guard wore a dark gray uniform and had a palpable air of intimidation about him.

To my surprise, he struck up a conversation with me at the threshold of the dining room on that final morning in Russia. In muddled, broken English he attempted to pose a question. I had trouble understanding. Eventually, he pulled out his wallet, revealed a 50-ruble bill, then pointed at me. I got it. I pulled out an American dollar bill and exchanged it for the 50. We shook hands.

“I love the American dollars,” he said.

Kyle Smaine enjoying his time in the Kamchatka white room. Photo: Matt Berkowitz

It turned out that diplomatic divide didn’t hold as much weight out here as back in reality. When I reached Moscow on April 14, traveling back to America, news broke of the U.S.-involved airstrikes on Syria in response to the Douma chemical attack. Russia, a Syrian ally, condemned the bombings, with president Vladimir Putin calling it “an act of aggression.” It was daunting news to discern after a week off the grid.

Back in Kamchatka, those headlines were irrelevant. The security guard went back to the front desk and I walked over to the coffee pot, both oblivious to the 24-hour news cycle. Later that day, Viktor, who I’d shared few words with, but several adventures of a lifetime, re-enforced the benevolence of Kamchatka and the therapeutic magic of skiing there. Before I walked out of the airport and onto the tarmac to my Moscow-bound aircraft, he gave me the wool hat off his head, which sported an outlined patch of the Kamchatka Peninsula. I’d expressed a liking to it one day at lunch. “I thought that this would be a good memory for you about Kamchatka,” he told me. No thanks (spasibo, “spaseeba”) needed. We nodded, shared a smile and I departed. Viktor, though, was going to stay awhile.

This story originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of FREESKIER (21.3), The Backcountry Issue. Click here to subscribe and receive copies of FREESKIER Magazine delivered right to your doorstep.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a YoColorado X Coors Banquet & Liberty Skis Prize Package](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1769630228-pastedgraphic-3.png?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)