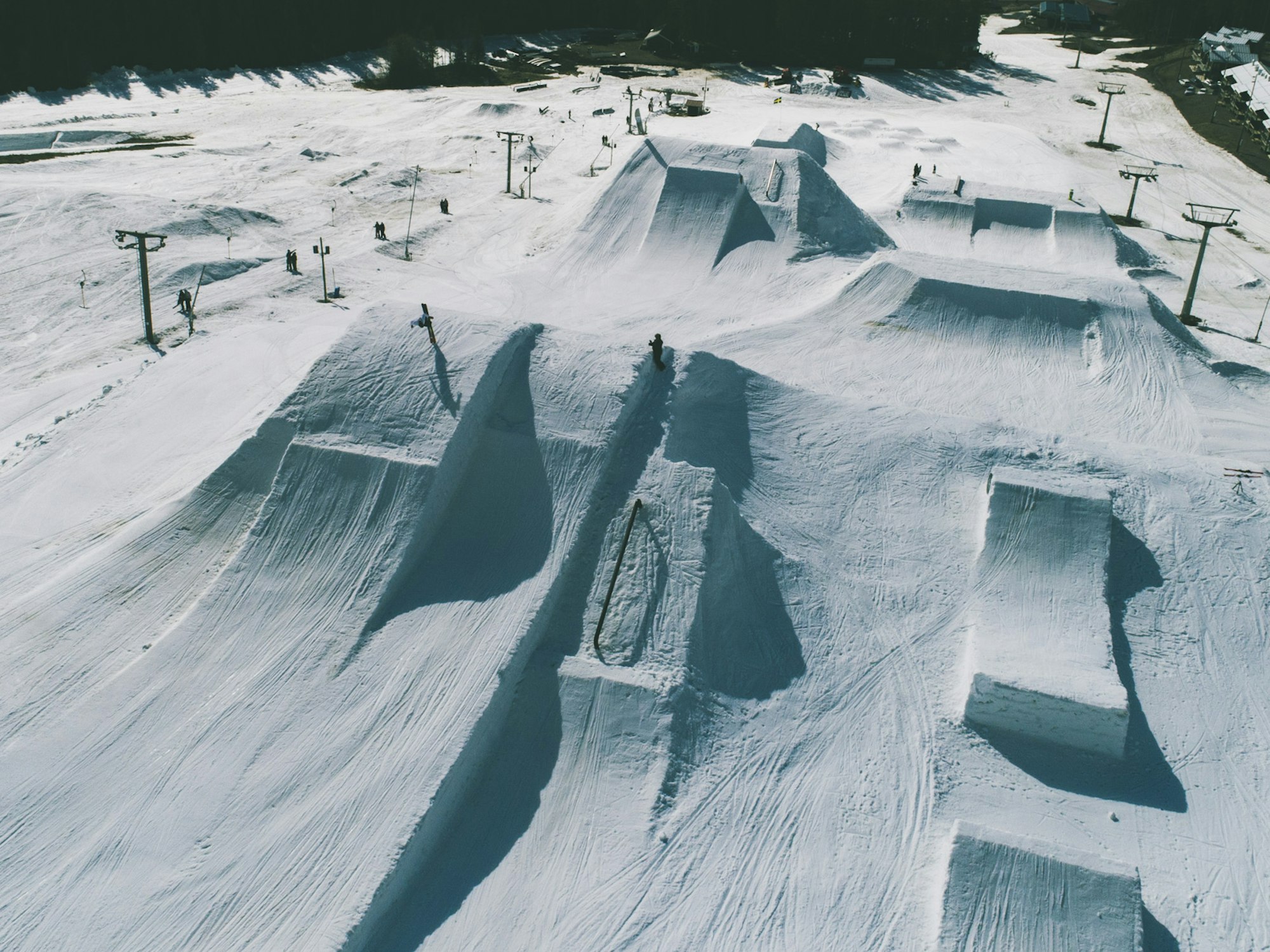

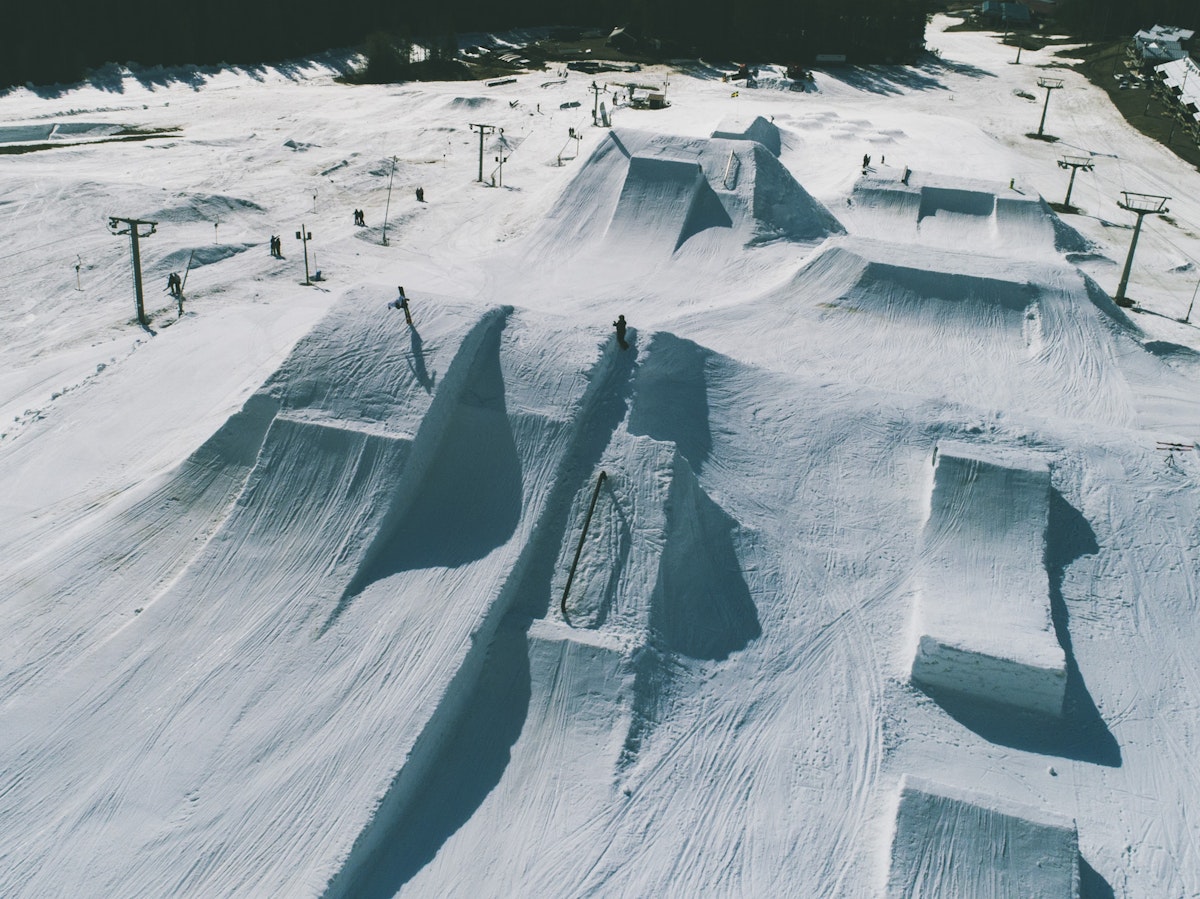

Featured Image: Daniel Rönnbäck | Skier: Daniel Bacher

Where does freeskiing live?

Depending on who you ask, you’ll get a different answer every time: perhaps it lives in the couloirs of Jackson Hole, the country clubs of Summit County, the steeps of Chamonix or maybe the yesteryear charm of Mt. Baker. But for six days in May every year, there is one definitive answer. Since 2014, a resort called Kläppen nestled in the mundane Swedish countryside has played host to a wholly remarkable gathering. The setting is humble—it feels “like you could be at Mt. Snow, VT,” according to two-time attendee Parker White. And yet, every year, 80 of the best skiers in the world, from the likes of Tanner Hall to the next gen make the pilgrimage six hours northwest of Stockholm for Kimbo Sessions.

PHOTO: Josh Bishop

Kimbo Sessions is fashioned after the Superparks of days gone by. These terrain park events used to dominate the pages of FREESKIER and now-defunct magazines like Powder and Freeze. Prior to Kimbo Sessions (often affectionately abbreviated simply to “Kimbo”), North American ski athletes would rarely see their European counterparts, everyone siloed in their own regional bubbles. Kimbo filled a gaping void in ski culture, bringing back to life an event at the end of the season that simply brings the people together to ski a slushy park. Kimbo is 50 percent unstructured park session, 50 percent community gathering, and everyone always brings their best.

The event isn’t easy to get to. Travel from North America might take days—multiple planes to get to Sweden, a long train or bus (or both) and a car ride after that. One might imagine such a journey would rely on financial incentives to pull the best skiers in the world—appearance fees, a cash purse for winners and sponsor incentives. Yet the opposite is true. “Nobody gets paid. There’s no $10,000 appearance fee. You don’t have to (pay people) to come,” says White.

If there’s no money in it, there must be prestige, right? The chance to win awards, land on the podium, boost the ego and feel like you’re a big player? Nope. Eponymous event organizer Kim Boberg clarifies: “The concept is to have no concept. Just to build a nice park and invite as many people as possible.” A gathering of the juggalos for baggy-pantsed park skiers, in essence. “That’s why Kimbo Sessions is as successful as it is because there isn’t any judge or any goal,” White adds.

One might assume that if there are no winners, losers or money to be won that the vibe is relaxed on-hill. A low-key slushy wind-down from a winter full of hard knocks battles in the streets and backcountry. It surely is, at times; yet the skiing at Kimbo Sessions runs the gamut—from slow moments to something ethereal that defies description. During Kimbo, there’s an energy in the air, an electric current that runs through Northern Sweden for six days.

PHOTO: Alric Ljunghager | SKIER: Benjamin Carlund

“Everybody talks about how it’s this super chill sesh. Yeah, kinda… except for it’s all the best motherf*ckers in the entire world all doing never-before-done tricks every run,” continues White. Kimbo Sessions is famous for moments where riders start to feed off each others’ energy, creating a chain reaction of magnetizing moments. “You feel like you’re buzzing, operating on a higher frequency. You get high.” The video and photo content that emerges from the event proves his point—a deluge of mind-melting nose- and tail-butters on the rollers, a profusion of brand-new axises on the jumps. Tricks the average human wouldn’t (couldn’t!) imagine.

For the first six installations of the event, we (the hungry audience) only had Instagram as a contemporaneous vehicle to consume this mind-bending content, with phone clips from Kimbo Sessions clogging our feeds. “Just making an edit from the event is a huge undertaking—even with no time restriction,” said Tall T Dan, whom Kim has worked with to run the @Kimbosessions Instagram for several years. Official recaps filmed on real cameras existed, but would typically drop months after the event had ended. 2022 was different.

Boberg hired Björn Eklund to film and edit three recap videos released in real-time as the event unfolded. This may seem like a simple task, but is monumental in execution given the timeline; there’s an insane amount of footage being logged on a filmer’s camera every single day, and that needs to be sorted before the editing begins. “You just did nine hours of filming. You got nine hours of footage. To feel some sort of mental clarity about editing those moments… is a huge task,” added Dan.

It’s no surprise that Boberg took on this challenge with Björn. The more one learns about Kimbo Sessions: The Event, the more fascinated one becomes with Kim Boberg: The Individual. Anyone reading this who has dabbled in event organizing—be that the small-scale endeavor of throwing a house party, or something much larger—can imagine the mammoth amount of logistics involved with pulling off a gathering of this magnitude.

PHOTO: Daniel Rönnbäck | SKIER: Kim Boberg

And yet, each year, Kim figures out how to make the event better—and it’s always been stellar. Dan expounds: “Year two, it was the best event in skiing. There wasn’t a person in skiing who didn’t want to go to the next Kimbo Sessions. But it comes down to the details.” Why not add more features to the park? Why not double the number of riders invited? How about adding a private chef to the event—and figure out how to have that person cook on-site at the top of the park? Dan finishes the thought: “I think it’s who [Kim] is, to always take it to the next level. It’s why successful people are successful. Kim has done that through his skiing for years.”

It might boggle one’s brain to learn that Kim spends October onwards planning the event near-full time, and still finds time to push himself as a pro skier. Kimbo Sessions occupies his brain “pretty much 24-7” according to Kim—and yet his best footage filming for movies has come since the inception of the event. XGames RealSki, Level 1’s “Zig Zag,” The Bunch’s “Color” and “Is There Time for Matching Socks” have all hosted extremely compelling Kim footage—and the best is yet to come.

Kim spent Winter 2022 in the States riding snowmobiles filming for the newest Deviate Films movie with Torin Yater-Wallace and Quinn Wolferman. The multitasking is nuts. “Being with him all year and seeing him in mid-February, he’s sending emails before going out riding and I’m barely getting out of bed, you know, like, where’s my coffee?” mused Wolferman. “He’s just the boss realizing what needs to happen. And if he doesn’t do it, no one will.”

PHOTO: Daniel Rönnbäck | SKIER: Torin Yater-Wallace

Kim is far from the first skier to run his own event: the Candide Thovex Invitational, the Tanner Hall Invitational, the Sammy Carlson Invitational, the B&E Invitational, Jon Olsson Super Sessions and the list goes on and on. Many have come and gone—few lasting more than a couple of winters. This coming spring will mark the 10th anniversary of Kimbo Sessions since the first gathering in 2014. How does Kim find the energy to keep on going?

Parker White knows the motivation: “Kim has one of the biggest hearts of anybody I know.” Kim may not be making money from Kimbo Sessions—in fact, the first few years he lost money, paying out of pocket for snowcat diesel when costs exceeded his sponsor revenue. But money isn’t the goal. Parker continues, “I don’t know if there’s anything in it for him financially. He’s just doing it out of love and passion, which to me is the most admirable thing that anybody could do.”

Parker’s musings provide the answer to our original question: There is no geographic home for freeskiing. No matter the location, freeskiing lives in the collective expression of passion at community gatherings like these. We can all learn something from what Kim Boberg created, nestled in a far-flung corner of one of the least mountainous countries in the world. Kimbo Sessions may have set a gold standard, but passion is blind—both to experience skills and geography. Whether you’re hiking a rail in the rain in Pennsylvania or skiing pow in Whistler—the activity doesn’t matter. What does matter is whether you invite someone to join you.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a YoColorado X Coors Banquet & Liberty Skis Prize Package](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1769630228-pastedgraphic-3.png?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win Nordica's All-New Unleashed 106](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1770321616-nordica.webp?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win Nordica's All-New Unleashed 106](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1770321616-nordica.webp?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)