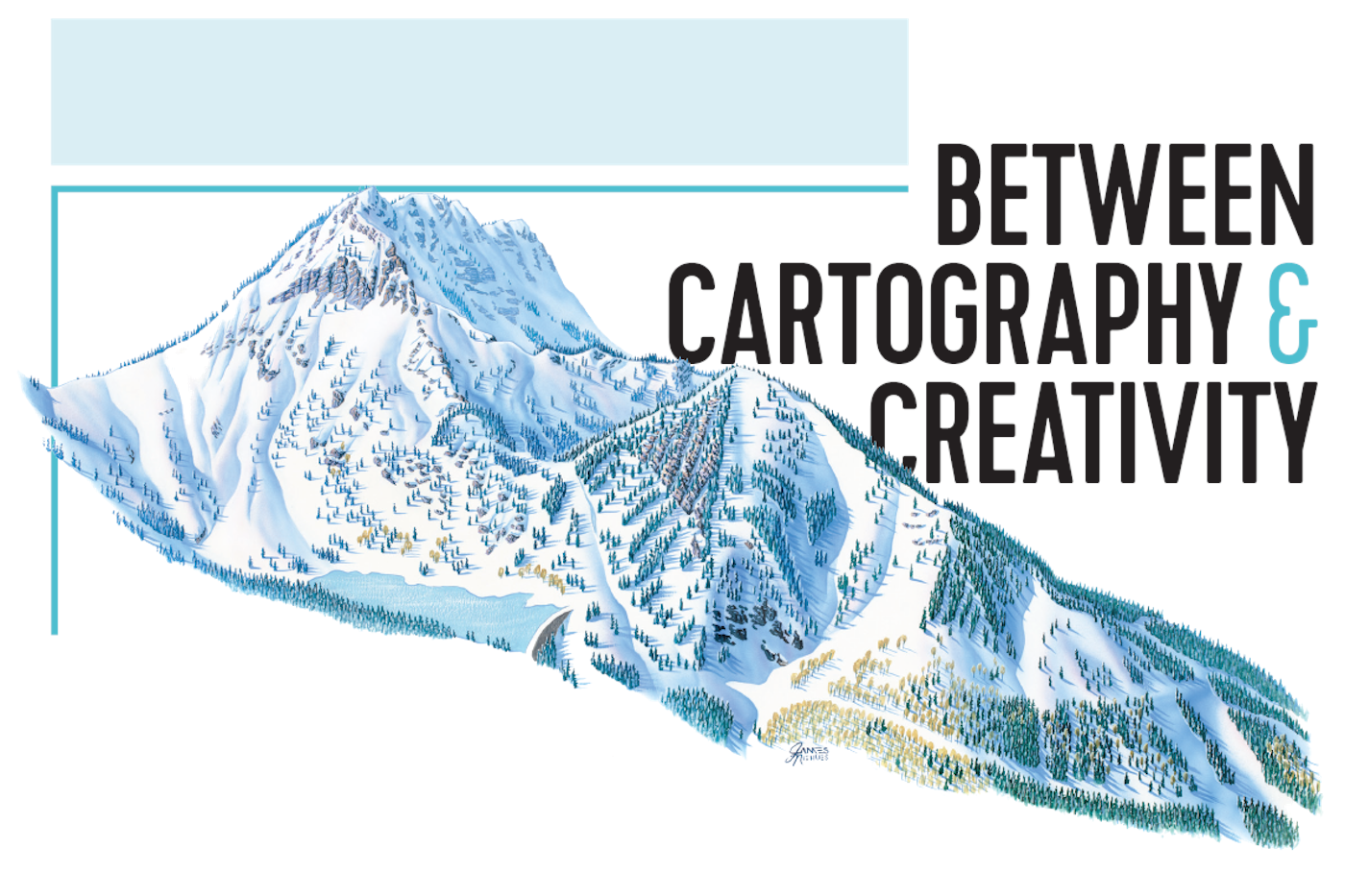

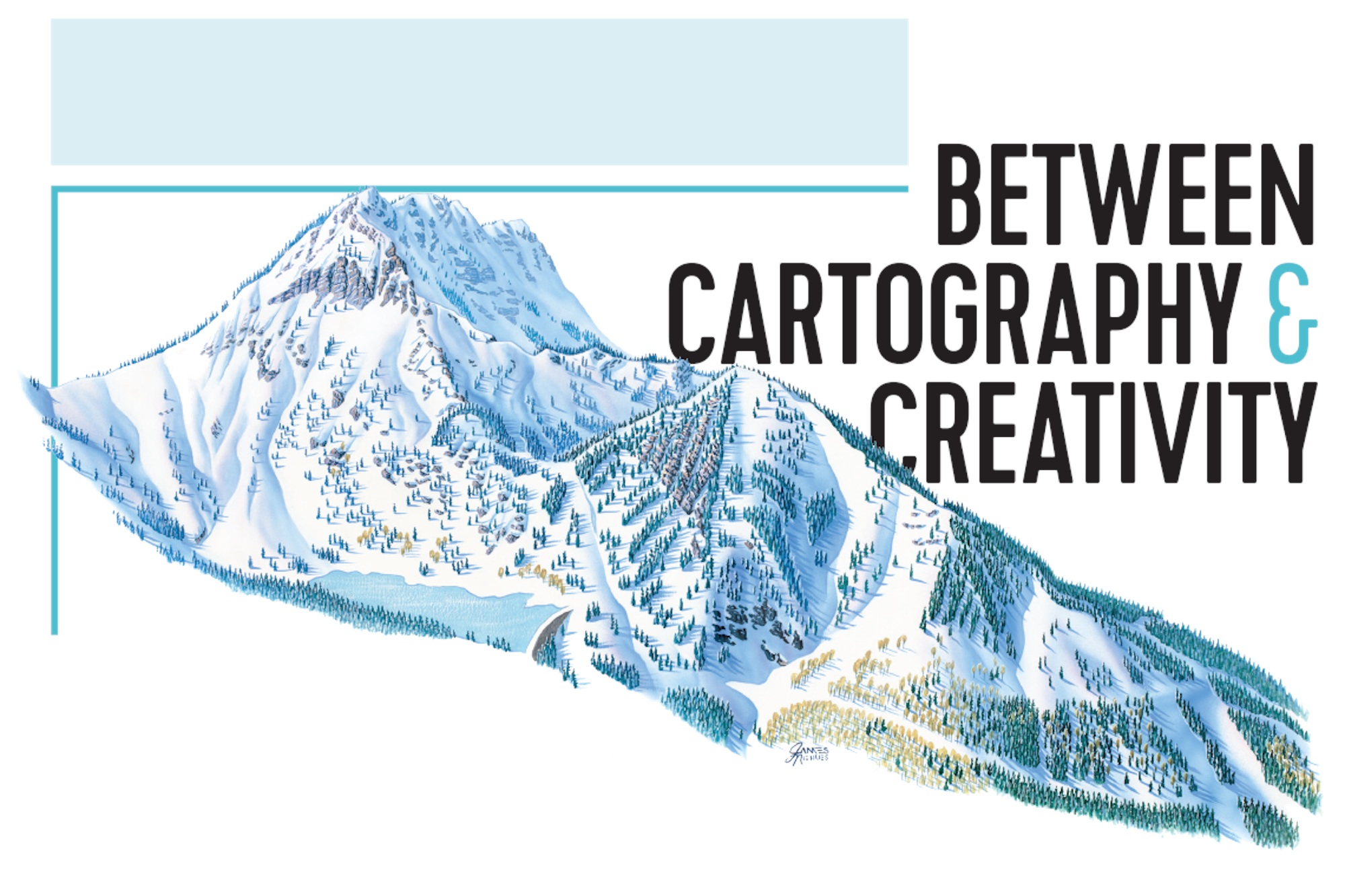

JAMES NIEHUES INTERPRETS THE SKIING EXPERIENCE ONE TRAIL MAP AT A TIME

The trail map is the resort’s fingerprint. It is the single-most exposed image that a ski area will use. There isn’t another image that will be more identifiable to that ski area than that map.

Pick up a ski area trail guide from the past three decades and it has most likely been designed by James Niehues, a landscape artist who has made his living painting watercolor maps for nearly 200 of the most recognizable resorts across the globe. From quintessential vacation destinations such as Big Sky, Vail, Portillo, Whistler Blackcomb, Jackson Hole and Alta, to small, local ski hills around the northeast and mid-west United States, Niehues’ work spans five continents and countries as disparate as Serbia, Japan and New Zealand.

Apart from the attentive audience who recognize his airy, meticulous style and notice his signature brushed gently in the bottom corner amongst the shadows of the forest, Niehues is not broadly recognized—yet his abundant portfolio has collectively aided in guiding millions of skiers in every discipline of the sport safely through vast, mountainous terrain.

Beginning at Grand Mesa College as a part-time illustrator and graphic designer, Niehues, now 71-years-old, was introduced to map-making originally by chance. However, the Colorado-native, with his honest admiration for the mountains, and innate ability to draw and paint, quickly recognized there was something uniquely exciting about “solving the puzzle” of accurately capturing the essence of a ski area on can- vas. Taking opportunity and skill in stride over the past thirty years, Niehues has quietly earned international acclaim as an artist who balances utility and aesthetics with every stroke of his paintbrush, undoubtedly influencing the modern skiing experience on a nearly universal scale.

The trail map is the resort’s fingerprint. It is the single-most exposed image that a ski area will use. There isn’t another image that will be more identifiable to that ski area than that map.

The way it’s always been done, starting right back with Hal Sheldon— the original trail map artist—is to go up and take aerial photographs, come back, do a sketch, take the drawing up to the ski area and have it approved. I do it just like Hal and Bill [Brown] in their day because I feel it’s the very best way to represent a ski area.

I prefer a small plane to a helicopter. Lots of times, I just can’t get he- licopters high enough… [which leaves me] looking horizontally, instead of vertically, at the mountain. But, if you get in an airplane, and you get up high—4,000-feet above the summit—you are getting a perspective like a satellite shot where you can just scan across the sky.

On my first and only visit to New Zealand, I was waiting for my flight [at the resort]… and pretty soon I could hear the helicopter. But it sounded funny and I couldn’t find it in the sky. Eventually, it came up over a hill. The pilot was a local deer herder who [the resort] had hired for really cheap… and the helicopter was just a little glass bubble with a Volkswagen engine on the back.

There was one time I got the shadows all wrong. All the aerial shots were taken on a cloudy day, and I didn’t get the lighting right. The shad- ows just couldn’t be in that direction at that particular resort. I had to go in and re-do the whole thing.

With the forest, there’s the first step of putting on the basic colors… then, I’ll come back and re-wet the canvas, which will bring out the highlights. Next, I’ll paint the darker, shadowed parts and, finally, there’s two more stages of adding the white snow and blue snow in the shad- ows. I’ve got a quite a few steps just for trees, and there are an awful lot of trees.

If it’s a steep area, I try to make it darker… more menacing.

When I was doing research for a map of the cross-country skiing routes around Mount St. Ann, in Quebec, it was so cold that our breath would condense on the inside of the windows of the plane—just ice on the inside. I had to get out a credit card and scrape the glass just to shoot a couple of shots.

I used to consider myself more of a cartographer in the fact that I was conveying something as accurately as I could… but, as time went on, I started realizing that the most important part of the process is the artistic aspect. It’s really not cartography—it’s not a measurement-by- inches. I’ve had some people ask me: “What instruments do you use to measure the slopes?” The answer is: My eyes!

Maps are part of our everyday lives, even when we don’t realize we’re using them. You gotta have a map of some sort to get around places you’ve never been. We just don’t recognize it today—it’s not always a piece of paper, it’s so often on a screen.

I can’t find the words for it… there’s just something about getting on the mountain that’s so refreshing. Standing up there, looking up, the wind blowing through the air; snow is coming off the trees and there’s just something so beautiful about that.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Head-to-Toe Ski Setup from IFSA](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765920344-ifsa.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Legendary Ski Trip with Icelantic's Road to the Rocks](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765233064-r2r26_freeskier_leaderboard1.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Head-to-Toe Ski Setup from IFSA](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1765920344-ifsa.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)