In a world obsessed with social media, avalanche centers are relying more and more on the attention-grabbing platforms to better equip backcountry skiers

WORDS • DONNY O’NEILL

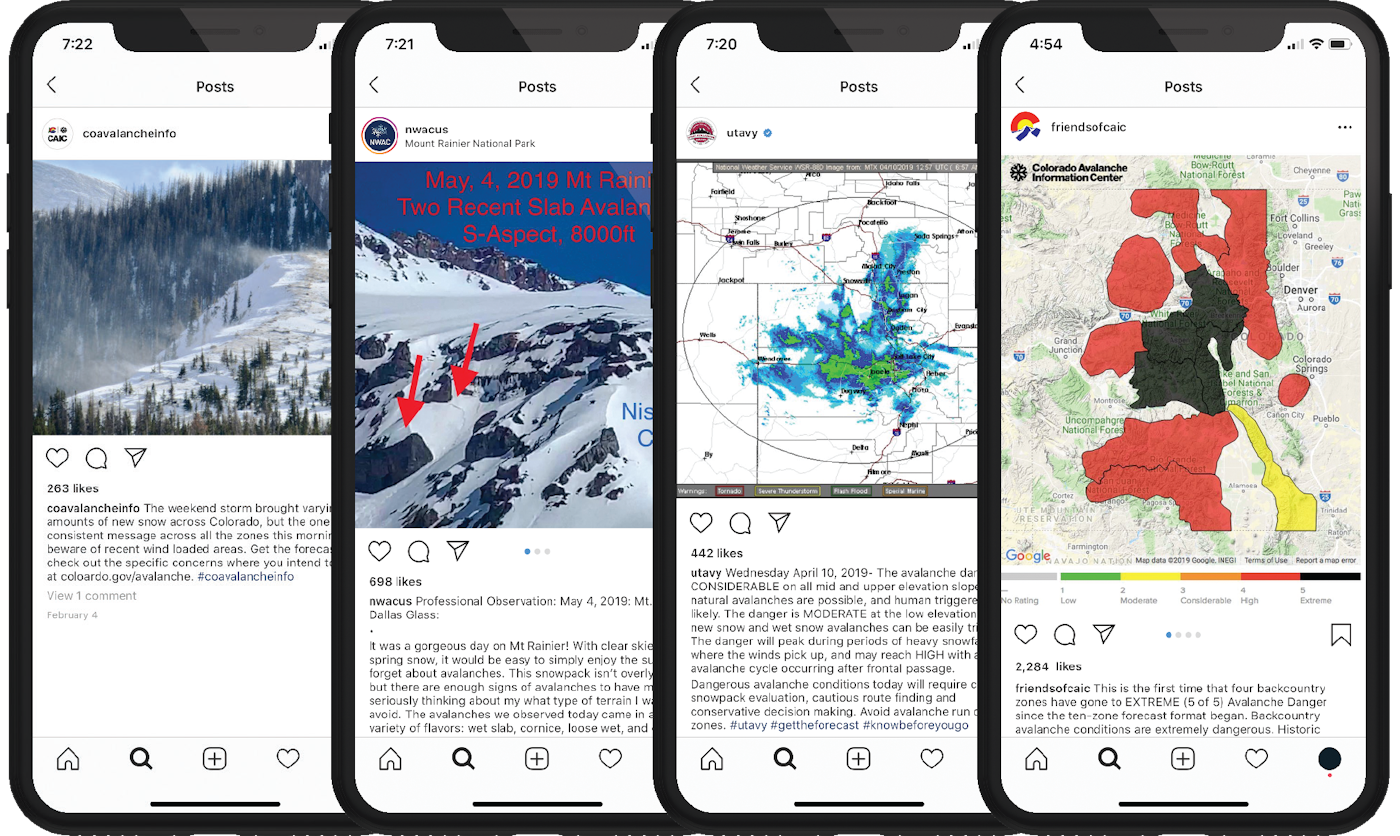

On March 7, 2019, central Colorado went black. For the first time since the state’s ten-zone avalanche forecasting format began, four backcountry areas—Vail and Summit County, the Sawatch Range, Aspen and Gunnison—were rated as having “Extreme” avalanche danger, marked in ominous black on the forecasting map. The Friends of CAIC, a non-profit organization tied to the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC), displayed the forecast map on its Instagram page, receiving over one hundred comments on the post. The engagement ranged from people tagging others to get the word out, asking questions about specific zones and relaying messages about safety and solid decision-making.

From February 28 through March 12, Colorado’s snowpack accumulated five to six feet of high-density snow that caused a historic avalanche cycle. The CAIC recorded data on 811 avalanches in that span, 142 of which were considered “very large” or “historic” in size. During that timeframe, the CAIC and Friends of CAIC posted a combined 36 times, a high frequency for both, on their respective Instagram pages, utilizing a combination of avalanche observations, weather forecasts and advisory graphics to ensure the public was informed multiple times daily of the complex and evolving avalanche danger.

It’s an effort being made by avalanche centers across the United States to better distribute information in a world that’s more consumed by social media than ever. Each individual center’s website, which offers current forecasts, upcoming weather discussions, staff-conducted and user-submitted observations, still remains the biggest focus, but Instagram, Facebook and Twitter serve to complement that.

“Originally, we looked at social media very much as another way of disseminating the forecast,” said Ethan Greene, director of the CAIC. “We still do that, but have been using it more to engage people and try to get out information about current conditions as well as broader education out to people. It’s been a good way for people to ask questions, and we’ve done our best to address those questions.”

The biggest challenge for the avalanche centers is exactly what information they are distributing and how they disseminate it. Certain conditions warrant specific real-time updates on evolving snowpack in the field, while utilizing the platform during less extreme cycles requires different types of posts.

“If avalanche danger is elevated, we would alert people to that and make sure to mention that there are rapidly changing conditions,” said Scott Schell, executive director of the Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC). “In other scenarios, we might simply post a photo from a day out, noting something we observed, if the conditions we’re experiencing are less dire.”

Regardless of current conditions, creating content in the field, while also diligently studying and analyzing the snowpack, has become part of the job description for avalanche forecasters.

“It is part of what they are actively doing. We are trying to improve the content that we get and train [forecasters] into knowing what type of content will be good,” said Greene.

To better inform its forecasters of what content will engage its social audience, centers like the CAIC and NWAC have brought in social media experts and consultants for training on content creation and writing.

The avalanche centers must also focus on making sure the content falls in line with the messaging they’re trying to relay on their platforms. They are constantly overseeing updates from the field to make sure they remain timely and won’t be misinterpreted by social media users seeking information that will dictate their behavior in the backcountry.

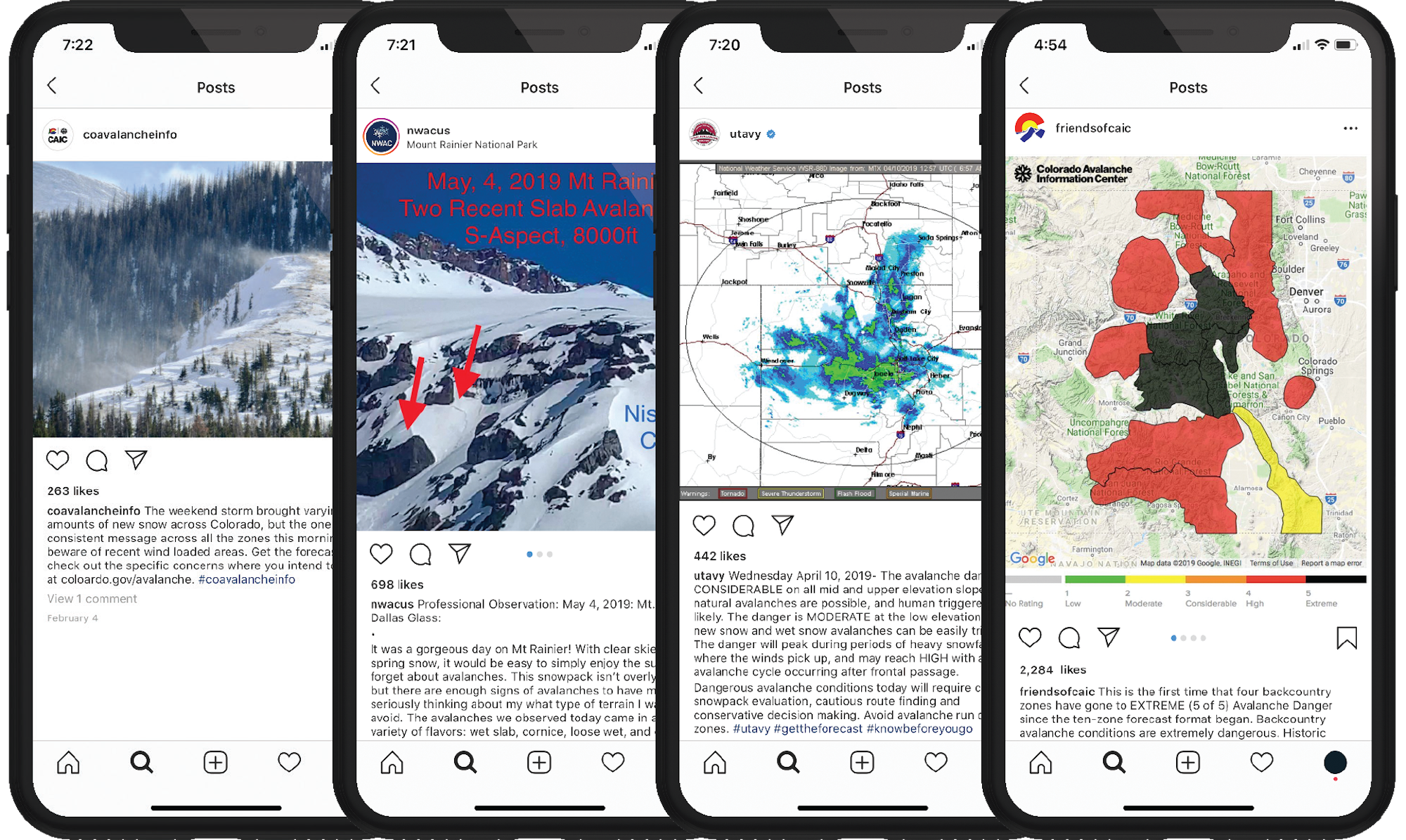

Two large avalanche crowns seen in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains after heavy snowfall in March, 2019. PHOTO: Scott DW Smith | LOCATION: Silverton, CO

“There are about 20 people who have keys to our various social media platforms, from our field staff, the non-profit staff, the forecasters and meteorologists,” said Schell. “We can post these real-time updates, but [we] could easily see how somebody would post something about what they’re seeing in [a particular] field that day, but, because our region is quite large, it may not accurately reflect the conditions across the whole zone.”

The changing social media algorithms, which are no longer chronological and alter when you see posts, have made it difficult to guarantee that the content reflects real-time conditions and problem areas.

“It’s been a real challenge point to figure out how we shift our media use and clarify location to make sure that people aren’t seeing and reacting to information that’s no longer relevant,” said Charlotte Guard, NWAC development and communications manager. “We’ll date the top of the post, then clarify between state professional observations or avalanche forecast updates—we usually bold that or put it in all caps. It’s a real pain in the ass, you never really know how the platforms are serving up content.”

Aside from conditions reporting, the avalanche centers are always looking to spread awareness, often by highlighting local classes or even posting images of a backcountry area and asking the audience to describe what they’re seeing, to ensure they’re always thinking and can translate those observations to the field.

“Social media is one of the best messaging tools that we have and it’s free, which is incredible,” said Bo Torrey, program director of the Utah Avalanche Center. “What we try to do is take complex topics and just chip away at them. We want to show people easily digestible tidbits of information to help them learn even if they don’t recognize that. We might prompt them with a question, or show an image with a simple question like, ‘Which way is the wind blowing?’ We’re helping to train people to recognize those subtleties, so when they go [into the backcountry] they’re already keyed-in on what to look for.”

Across the board, avalanche centers have cultivated audiences willing to engage and join the conversation about local avalanche safety. Torrey notes that “people from all over the country make up our user base,” and the users are actively engaging with posts from the beginning until the end of the season to better prepare themselves for trips to the Beehive State.

The backcountry skiing community is a close-knit one that, for the most part, looks out for one another. Schell believes by humanizing the avalanche forecasters and their process, it’s promoting more and more engagement on social media.

“The goal is to augment the forecast in a way to make it a lot more personal and, I think, connects with people better,” said Schell. “When you use formal public risk communication along with social media and you nail it, there’s a lot of good synergy between the two products. Ultimately, the point of it all is equipping people to stay safe and make good decisions.”

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a YoColorado X Coors Banquet & Liberty Skis Prize Package](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1769630228-pastedgraphic-3.png?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)