An unassuming Norwegian hotel is leading the future of backcountry skiing by rooting firmly in its past.

WORDS • TOBIN SEAGEL | PHOTOS • MATTIAS FREDRIKSSON

I forgot my ski crampons again. At this point, I decide to go for the “stomp and pray” technique, willing my edges to hold in the firm, slippery snow and hoping each subsequent false summit we encounter is actually the real thing. Regardless, it’s still a smashing day in the Norwegian mountains, so I happily distract myself by enjoying the everlasting vistas and serenity. Soon the snow softens, and my skins grip. I find a rhythm, and it’s relaxing to slowly glide uphill through the mountains. One hour and 500 vertical meters later, I finally get a glimpse of the rounded summit where I join the rest of our group hiding from the wind behind a small, snow-filled wooden shelter at the top of Urdshovd, 1,445 meters above sea level.

Yesterday, I left Bergen by train for Vatnahalsen, a remote hotel outpost tucked in the Aurlandsfjellen in Norway’s Vestlandet. I was accompanied by Giulia Monego, an Italian mountain guide and former Verbier Extreme champion; Swedish photographer and Canadian transplant Mattias Fredriksson; and Norwegian filmer Matias Myklebust. The only way to get to Vatnahalsen is by electric train; daily trains arrive from Oslo and Bergen to Myrdal Station, where passengers connect to the local Flåm Railway. The latter is one of the steepest trains in the world. It descends nearly 900 vertical meters at a five-and-a-half percent gradient from the mountains to the village of Flåm—an old Viking settlement dating back to 1340, located at the inner end of the Aurlandsfjorden, a branch of Sognefjorden, the world’s second-longest fjord. Construction on the line began in 1924, but the 20 hand-dug tunnels took almost 16 years to complete, delaying the railway’s opening until 1940. It has been fully electric since 1944, and though it was established to facilitate trade between Norway and the rest of Europe, today the train is one of the top summer tourist transports in the country Its popularity in winter may well increase once skiers discover that it’s the key to unlimited terrain and an incredibly welcoming hotel.

As soon as we walked off the train, we met our host for the week. Dressed in faded white New Balance sneakers, old blue Levis 513s and a well-loved red sweater, the 46-year-old owner of the hotel, Petter Andreasen, greeted us at Vatnahalsen’s train station with unmistakable warmth and the curtness of a seasoned mountain guide. Petter’s passion for skiing was evident as he quickly dispatched introductions and small talk to get to what mattered—how soon we could be ready to ski. He was accompanied by his 13-year-old border collie/springer spaniel Viggo, who rarely left his side throughout our visit. We ambled up the short hill to the hotel, a quintessential Norwegian red building built in the romantic Dragestil (Dragon Style) design with exposed timber walls, steep roofs and big eaves.

Earn your turns up the mountains, ski powder down anywhere you’d like and then board the Flåm Railway to go back up to the hotel for another “våffla.”

Behind us, the train pulled silently out of the station towards the fjords below, made a full 180-degree turn in front of ice-covered Lake Reinunga, past a speckling of small red and yellow cabins, sounded its horn and disappeared into the side of the mountain.

Standing at the hotel, mountains rose above us in every direction, big rounded masses carved intricately like etchings on upside down vases. The longer we looked, the more ski lines we saw—couloirs, freeride terrain, alpine steeps and beautiful, gentle terrain, too. Below us, a long valley sneaks 20 kilometers to Aurlandsfjorden, the electric rail line carved impossibly into its steep walls. It is hard to understand how backcountry skiers overlooked this area until 2015, when Petter first checked it out.

Less than an hour after our arrival, we were on skis and touring up the mountain. We navigated through the dense forest and reached the subalpine after just 20 minutes on the skin track. I looked back at the Vatnahalsen’s red buildings standing out in the white, rolling landscape, surrounded by mountain peaks.

Chamonix-based mountain guide, Giulia Monego, felt right at home in Vatnahalsen’s steeper terrain.

We kept our first tour short, but we didn’t have to go far to realize Vatnahalsen’s potential. It might not be the most rugged collection of mountains in the country, but the ski terrain is impeccable and very dynamic.

It was a dry winter in this part of Norway, however, as luck would have it, a big storm the week before our trip filled everything in nicely. When we dropped in on the northwest face towards Myrdal, the flakes were fresh, the snowpack felt good and the 30-degree pitch skied perfectly.

The flurries in the air and the milky skies made navigating uphill difficult, but we followed a cliff wall for visual reference on our descent to Myrdal Station, and I could let it go and really open up some turns. At the bottom, I looked back and witnessed Petter and Viggo rip down the powder together, like the two best friends they are.

“It would feel very empty to not have Viggo with me when I’m skiing. He is always with me since I often go to the mountains, alone,” says Petter. “He loves it, and he is super funny. The guests love him, too. He leads the way, which is very useful on white-out days.”

The spiritual, almost primal, connection between Petter and Viggo reflects the soulful character of the entire region. Together they set the mood at Vatnahalsen that makes the place so unique.

The Vatnahalsen Hotel is as Norwegian as it gets. Skins on right outside the door.

“Long ago, I passed by [Vatnahalsen] on the train between Oslo and Bergen. As the train went by Myrdal, I thought to myself, ‘There must be great ski terrain in these mountains,’” Petter says. “I moved to Lærdal, just a few hours away, and a friend asked me if you could go up on the Flåmsbanan and ski there. I had never taken the train up here before, so I went up with a few friends to check it out.”

Petter’s eyes widen, and his hands rise exuberantly as he describes his first time skiing at Vatnahalsen.

“It was a perfect day, good snow, blue skies and not a single track in the mountains. Back at the hotel early that evening, I called the owners and asked if we could come back the next weekend,” he says.

Petter Andreasen, the owner of Vatnahalsen Hotel, points out all the skiing opportunities in his backyard to Giulia Monego and Tobin Seagel.

Built in 1896, the Vatnahalsen Hotel has operated mainly as a summer destination, but springtime Nordic skiers began to arrive in the 1930s. At one time, Vatnahalsen was even known as the St. Moritz of the Nordic, as the “rich and famous” came from all over Europe to ski and enjoy the fresh air of the Norwegian mountains.

As ski resorts were constructed elsewhere in the country in the 1950s and ‘60s, mountain hotels like Vatnahalsen quickly lost their clientele and shuttered their doors. The Rallarvegen, a road built to service the construction of the Bergen Railway in the late 1800s, kept Vatnahalsen alive. Rallarvegen winds 80 kilometers through the mountains between the interior plateau of Haugarstøl on Hardangervidda and the fjords of Flåm. It’s become a popular hiking and biking route in the summer—and everyone stopped in Vatnahalsen to rest, enjoy the views and refuel with waffles.

However, until Petter arrived a few years ago and introduced the backcountry ski community to the potential of the area, the hotel was in the red every winter.

“No one understood the beauty and potential of skiing at Vatnahalsen. The former hotel owners were not skiers and barely had the hotel open in the wintertime,” says Petter.

It’s appropriate that the path to owning one of the most unique ski hotels in the world is paved with serendipity and a little bit of magic. Born in Oslo, Norway, Petter learned to ski as a kid and has been passionate about the sport ever since; that background has been his compass. Though he is best described as an entrepreneur, Petter’s ambitions are not about the money.

Petter’s career began in the multimedia business in 1995, and he sold his company right before the dot-com crash. Free from business commitments, Petter spent several years traveling through Mexico before moving to the mountains of Chamonix, France, where he opened “Goofy’s” (now Moo Bar), a skiers’ après joint in the heart of town and ran it for six years until getting the itch to move on again.

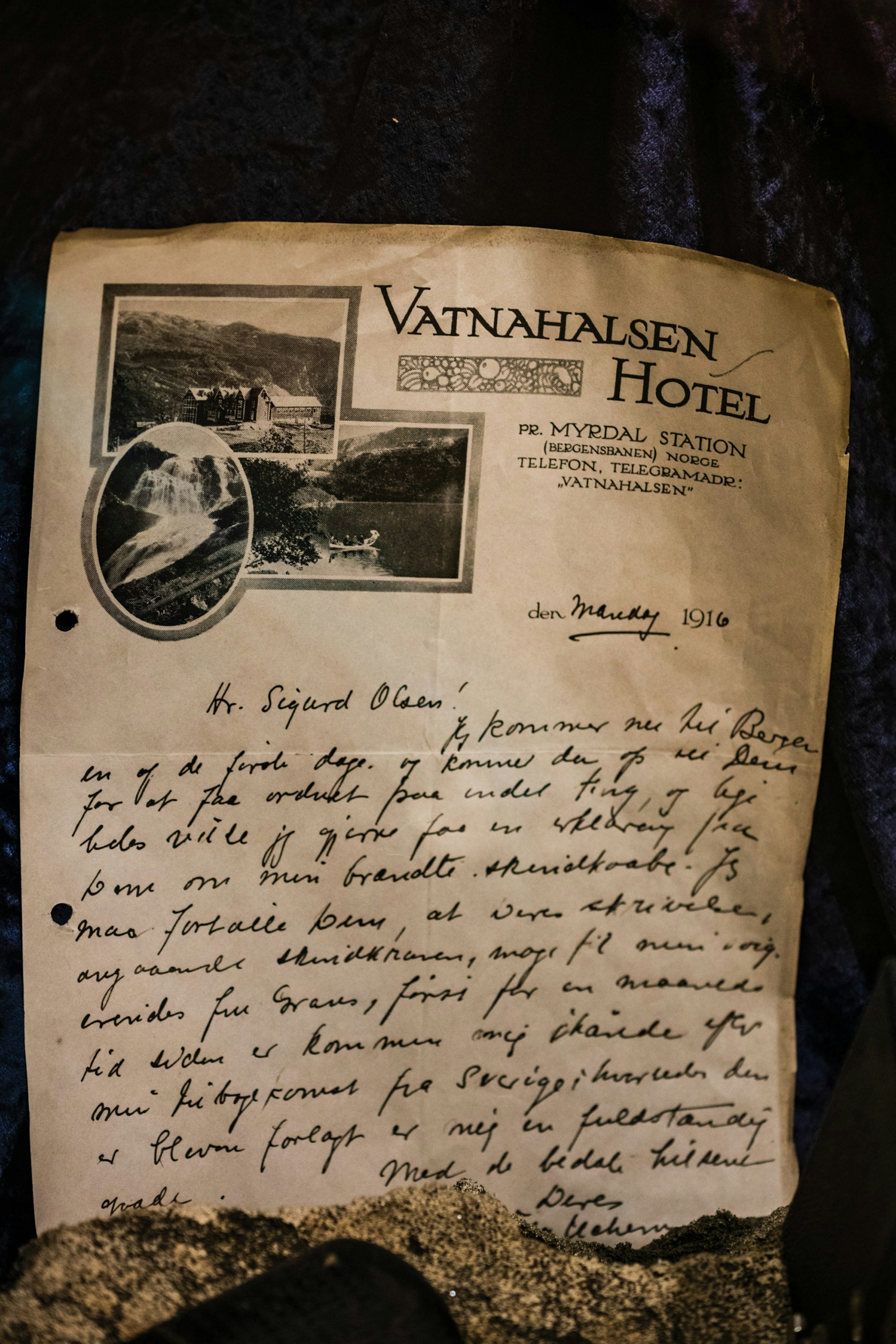

This appreciation letter from a guest to the hotel owner is dated back to 1916.

In 2003, turned off by the business scene, Petter moved to Copenhagen, Denmark, and worked as a social worker for kids with developmental disabilities. Eventually, he moved home to Norway and reinvented himself again. He became a raspberry farmer in Lærdal, near Sogndal, where he had the months between October and May off, giving him the opportunity to ski all winter.

After discovering Vatnahalsen in 2015, Petter brought more friends up for weekends. They formed a small ski community that gave the old hotel an unexpected buzz. In the fall of 2015, he got a call from a real estate broker. The Aknsne family, who owned Vatnahalsen, decided to sell the hotel, and they figured he might be interested.

“All of a sudden, I became a hotel owner together with my dad, my brother and some investor friends. Just like that!” says Petter.

Petter’s goal of getting involved in career ventures out of passion, not monetary gain, richly rewarded his strategy this time. With ownership of the hotel, his life circled back to skiing.

“If you focus on making money, you are not going to succeed,” says Petter. “For me, it is about making people happy and having a good time.”

Fly into either Oslo or Bergen, depending on your budget. Then you’ll need to grab a train ticket from either city to Myrdal Station, where you’ll transfer to the Flåm Railway en route to Vatnahalsen. All transport to and from the hotel is via train.

The hotel offers multiple package options—including ski tour outings, fjord safaris and summer ziplining—for a truly unique experience. For more information on booking, visit vatnahalsen.no

Petter knew he was on to something special and went out of his way to keep the vibe authentic. Instead of traditional marketing, he brought people to Vatnahalsen who would appreciate this unique place and spread its magic via word of mouth.

“Keep it mystic! For us, the best way to promote this place is via social media and to keep inviting the right people here,” says Petter. “Over the years, I have also worked with some of the best guides in Scandinavia. They have been essential promoters for Vatnahalsen.”

Calle Lundberg, a Swedish mountain guide based in Stockholm, was one of the first guides to visit. Calle had guided all over the world. After hearing a podcast by Johan Roxström from the Stockholm Resilience Center, a sustainability think tank at Stockholm University, Calle became more aware of his lifestyle’s carbon footprint and felt increasingly guilty. He looked for alternate ways to reinvent his guiding business by only taking clients to destinations and mountains that could be reached by public transport like buses and trains.

“At first, I thought my new direction would make things difficult and complicated. I even thought it would be challenging to continue my career as a traveling mountain guide,” says Calle. “Looking back, I can honestly say things turned out much better than I thought, and instead of losing clients, I have grown my list. There are a lot more people out there today that are cautious about their travels when they go skiing.”

Calle takes clients to Vatnahalsen several times a year and happened to be at the hotel during our stay. On this particular trip, he and his clients took the train all the way from Stockholm, via Oslo, to Vatnahalsen—roughly a 16-hour journey.

“The train is such an excellent way to travel,” says one of his enthused clients. “You can sleep, drink, read and watch the world go by.”

Petter Andreasen and his dog, Viggo, in action.

Toward the end of our trip, while ski touring from the hotel, we briefly followed the railway tracks towards the fjord. We joined the classic Rallarvergen contouring the cliffy landscape to where the trail meets the Myrdal River as it falls away 300 meters in a series of spectacular frozen cascades. From there, our journey headed up through the typical Scandinavian, crooked, black sub-alpine birch trees before we gained a set of beachball benches in the alpine that gave me butterflies, like touring up the edge of the world.

Rising almost one and a half kilometers above sea level, the summit of Urdshovd, where this story began, provides 360-degree views to all the surrounding peaks. On beautiful days like this one, we can see the Rondane, Galdhøpiggen and Hårteigen mountain ranges on the Hardangervidda mountain plateau. To the southeast, a steep glacier-cut valley leads to Aurlandsfjorden, and we see the Flåm Railway clinging to the mountainside a kilometer below.

SKIER: Tobin Seagel.

SKIER: Giulia Monego

“This was the very first ski tour I did here, and possibly the first descent in the area. Nobody skied up here before,” says Petter.

We hurriedly finish our sandwiches—the lunch Norwegians typically prepare for outdoor adventures—take a few obligatory summit selfies and step into our skis. The first few hundred meters are teeth-chattering ice stripped clear by the Atlantic wind, followed by some character-building breakable crust. But it soon gives way to buttery powder turns as we ski into a sheltered hanging valley. Hoots and hollers ring out from our crew as we make high-speed turns with postcard views in every direction. From the hanging valley, we follow a snow-covered stream to the top of an open rock face with views down to the railway another 100 meters below. We delicately work our way across some steep benches, over a series of boulders and through the gnarled black birch trees to reach the base of the hill.

We finally spill out into a farmer’s field in the valley of Ugjerdsdalen, by Kårdal station and Kårdalsfossen waterfall. We re-join an old, snow-covered road and skate our skis down beside a crystal-clear river under vast cliffs to Blomheller Station. The immense overhangs festooned with blue icefalls are spectacular. Though the station is nothing more than a small yellow building, it provided welcome shelter to cut the wind and warm us up while we waited for the train back up to the hotel.

We hitched a ride on the locomotive, and a half-hour later we’re making waffles from the self-serve waffle bar in Vatnahalsen’s 1960’s-style hotel living room. Flower curtains frame the windows, with black and white photographs scattered around the room. Skiers, just in from their tours, relax in the well-loved leather chairs.

“Waffles and coffee are free for skiers. Even if the snow was shitty, there’s always something to look forward to [in the lodge],” says Petter, as he spreads whipped cream and raspberry jam on his honeycomb-shaped treat.

Left: The train dictates the pace at Vatnahalsen, yielding a very relaxing atmosphere. Right: Giulia Monego, Petter Andreasen, Tobin Seagel and Viggo ski touring up to Urdshovd, high above the Vatnahalsen Hotel.

Vatnahalsen is about the total experience, not just the skiing. From hanging out with fellow guests in the main living room to enjoying homemade snacks after skiing and sharing a beer at night, the atmosphere is warm and friendly—like staying in someone’s home. The staff is happy, and that makes the guests happy; I can still hear the sound of the bartender’s joyful, booming laugh whenever he spoke with a guest. It is simple living, no luxury. The good food—often locally sourced—served family-style, provides a more profound feeling of satisfaction than you will find in any five-star resort. Vatnahalsen provides all you need. No more, no less.

There are no other restaurants or bars; it is all happening at the hotel. It is isolated and intimate; a place to socialize and hang out. Like the hotel, the people there seem genuine, and new friendships are built quickly. It feels very disconnected from the usual rhythm of life. It is just about having a good time and enjoying nature.

“The people that are here, they are here, and nobody else will come or go. The fact that you cannot get here in any other way than the train creates a unique feel,” says Petter. “The easy access to the skiing is exceptional, too. You put on your skis straight out the door, walk up to any mountain you see and ski down in any direction.”

As the ski industry amalgamates into larger entities and a more uniform experience, as climate change makes us question how we approach the outdoors and as our lives are further influenced by smartphones, it can be easy to lose sight of the simple connections and experiences that drew us to the mountains in the first place. Some people are looking for more than what can be offered by the mega-resorts, five-star heli lodges or posh experiences. Perhaps this unassuming Norwegian hotel is leading the future of backcountry skiing by staying true to its roots. It provides a slower, more authentic way of life that is a rarity today. And even if you’re not seeking human connection, the skiing is pretty damn good and the waffles irons are always hot.

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Limited Edition FREESKIER Hat](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1772568976-3x4a9169.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)