HOW ADAPTIVE SKI PROGRAMS ARE GIVING THE INJURED THEIR LIVES BACK

IT’S A COBALT-SKY, 13-inch powder day at Tahoe’s Alpine Meadows and Matt Leonard is on the bunny slope. This isn’t exactly where Leonard, a 29-year-old avid skier who grew up in Vermont and now lives in San Francisco, wants to be. He can see the top of the mountain from his perch on the resort’s green-circle Subway chair and he knows there’s a foot of fresh slathering the steeps on the peaks above him. But today, this flat, groomed run is where Leonard will be skiing.

Two years ago, in late February of 2015, Leonard caught an edge while skiing those very steeps at Alpine Meadows. A strong, confident skier, that day, a freak misstep changed his life. He lost control and slammed into a lift tower.

The crash broke his back, a T4 spinal cord injury that rendered him paralyzed from the chest down. Emergency crews took him to a trauma center in nearby Reno, Nevada, and eventually he was transferred to Colorado’s Craig Hospital, which is renowned for its spinal cord rehabilitation.

In Colorado, Leonard learned to perform the everyday skills that most of us take for granted—tying his shoes, going to the bathroom, showering, getting dressed—only without the use of his lower body. Occasionally, during his months-long stay in the hospital, he would fantasize about skiing.

“You lose so many things, but as you’re adapting to life again, you pick up the skills you need to get through,” says Leonard. “Hobbies and recreation may be some of the last things you learn again, but they’re definitely not the last things you think about.”

Leonard applied for a grant from Truckee, California-based High Fives Foundation, a non-profit that helps people who’ve sustained life-altering injuries, and through the organization, he received everything from massage therapy to acupuncture to aid his path to recovery and help him adjust to his new life in a wheelchair.

The grant also included a lesson from Achieve Tahoe, a non-profit that provides summer and winter recreation for those with physical and mental disabilities. Achieve Tahoe has been around for 50 years—it’s the longest operating adaptive sports program in the U.S., and it just so happens to be based at Alpine Meadows, ground zero for Leonard’s injury.

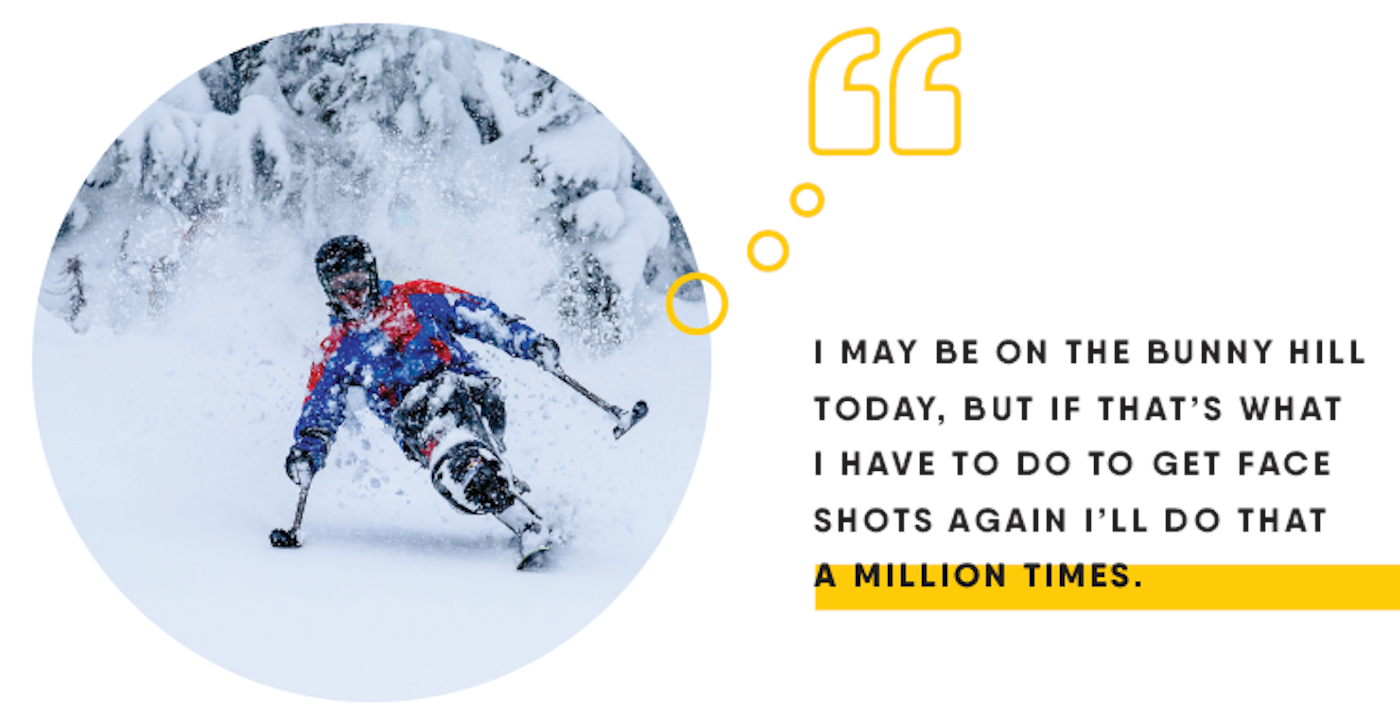

Just one year after his crash, Leonard sat in a sitski—basically a bucket seat on a monoski that enables those with lower-body paralysis and other injuries to ski—at Alpine Meadows and slid down the beginner slope with help from an instructor.

“It was hard physically. I was struggling with strength and stamina,” he says of his first time back on skis after his accident. “It was also hard mentally. I just wanted to get on the hill again and get over that mental hurdle.”

Another 12 months passed. He quit his job at a tech software company in the Bay Area and he decided to try skiing again. “I feel confined,” he said on that powder day last February when he felt stuck on the beginner slope. “But I’m trying not to let it get me down. It’s got to be motivation to get better. I may be on the bunny hill today, but if that’s what I have to do to get face shots again I’ll do that a million times.”

Adaptive sports programs exist around the country—most major ski hubs have an organization that helps people experience that rush of sliding down a snow-covered mountain even after their bodies have been through irreparable trauma.

From the Wasatch Mountains to Breckenridge to Vermont to Liberty Mountain, Pennsylvania, adaptive programs are literally turning lives around. Across the world, too, more and more ski resorts and specialized programs are making the impossible possible. For example, the Swiss ski resort, Klosters-Madrisa, recently built a new six-person chairlift designed to make it easier and safer for those on adaptive mono-skis to load the chair by themselves.

“These programs provide incredible results with positive impacts on the athletes’ lives, getting them back out to the sports they love,” says Roy Tuscany, the co-founder and executive director of the High Fives Foundation. Tuscany broke his back skiing in 2006 and three years later, he founded High Fives to help others in the same situation he found himself in. “In the simplest terms, these programs allow individuals with disabilities the opportunity to enjoy sports in a safe, fun and exhilarating way by almost eliminating the disability and just focusing on the sport, not their injury.”

A camp for children with serious illnesses, called Double H Ranch in New York’s Adirondack Park, has an adaptive winter sports program that came up with a way to get an 11-year-old boy who is both blind and deaf out on skis on his own, using a tethering system that gives him vibrational cues on his wrists to signal when and where to turn.

Ski towns across the country are making it easier for adaptive athletes to get into the backcountry, too. Telluride Adaptive Sports, in Colorado, offers everything from ice climbing to backcountry touring to heli skiing for adaptive athletes. Steamboat Powdercats, in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, hosts a four-day adaptive cat-skiing trip each winter, and a catskiing outfitter near Whitefish, Montana, called Great Northern Powder Guides hosted their second annual adaptive backcountry camp this past winter.

“There are other programs like this around the country—and our collective goal is to show people that this is achievable,” says Haakon Lang-Ree, Achieve Tahoe’s executive director. “We designed our programs to be around high-challenge, destination sports. So people with disabilities can have the same opportunities to go out and do [these activites]. They’ll get the same benefits as anyone would get from skiing: They run the gamut from exhilaration to solitude to socializing to exercise.”

Achieve Tahoe was formed in 1967 by a World War II veteran and 10th Mountain Division skier named Jim Winthers, who gathered a crew of Vietnam vets to learn how to ski.

Last February, Achieve Tahoe hosted their annual military sports camp, which brought together 17 injured veterans for a few days of learning winter sports at various resorts around Tahoe. Among the group, there was Richard Alcaraz, a 45-year-old former snowboarder from Arizona and a Marine Corps vet from the Gulf War. Alcaraz’s left leg was amputated below the knee after a motorcycle accident. He’s done triathlons and played ice hockey, basketball and lacrosse, using a prosthetic leg or a wheelchair, but he hadn’t been skiing. “At first, I was skeptical,” Alcaraz says. “But I see people who don’t have legs and they’re doing it, so I know I can do it, too.”

There is Larry Celano, a 47-year-old father of three who suffered a spinal cord injury from gunshot wounds when the U.S. invaded Panama in 1989. During the camp, when he learns how to steer his sitski unassisted down a gentle grade on Alpine’s Subway run, he hollers with glee—a triumphant “Yeeehawww” that makes everyone around him smile.

And then there is Mariela Meylan, a 38-year-old U.S. Army veteran who was hit by a truck while changing a tire in Iraq in 2005 and sustained a traumatic brain injury. She is quiet, focused, more determined than anyone around her. It’s hard to tell if she’s having any fun in her sitski, but eventually, after a few tries and signs of success, a sly smile creeps across her face.

“These people have been in a similar situation as I’ve been through,” she says, slowly and methodically, about her fellow veterans. “They know what to expect.” She pauses for what feels like a long time, then adds, “what needs to be done. What can be done.”

“In the disabled population, there’s a lot of stigma, or negative reinforcement,” says Achieve Tahoe’s Lang-Ree. “There’s more for them to overcome than able-bodied folks. There are other hurdles and barriers. But we think if you can do this—if you can ski—then you can do anything. That’s our whole motto.”

For these men and women, skiing becomes a way to heal, a path to transcendence. It enables the disabled and helps them overcome perceptions of what the rest of the world might see as unfathomable. How can a man with a severed spinal cord, who feels nothing from his mid-section down, possibly ever ski powder? Can a man who can’t feel his feet feel a face shot? Sure he can.

Just ask Matt Leonard, the wheelchair-bound Vermont native. “I know I’ll get face shots again someday,” he says, positively sure. “I’m lower to the ground now, so it should be easier, right?”

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Limited Edition FREESKIER Hat](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1772568976-3x4a9169.jpg?w=200&h=200&fit=crop)

![[GIVEAWAY] Win a Limited Edition FREESKIER Hat](https://www.datocms-assets.com/163516/1772568976-3x4a9169.jpg?auto=format&w=400&h=300&fit=crop&crop=faces,entropy)