WORDS • JAAKKO JÄRVENSIVU | FEATURED IMAGE • JAKOB SCHWEIGHOFER

Prologue

We’re sitting on sofas made out of pallets in a wooden ex-warehouse building. Together with the chunky ceiling beams and the wood-fired stove to my right, the décor has a certain rustic vibe common in trendy cafés. On my left is a workbench, but instead of a state-of-the-art espresso machine, standing behind is a row of skis with two banners, one with the initials “B.A.M.” and another with just one word: “Pindung.” The initials stand for Bavarian Alpine Manifest, a young and innovative ski binding company on the verge of an international breakthrough. Sitting next to me is the company founder Markus “Bam Bam” Steinke.

Steinke, who got his nickname referring to the Flintstones character some twenty years ago on a road trip to lake Garda, is sporting three-day-stubble and his blondish hair is tied up in a pony-tail. Clad in a light-green Patagonia t-shirt, blue shorts and hiking shoes, he could pass for a happy-go-lucky ski bum. Now, with our discussions nearing their end though, after the mandatory marketing-talk of a startup CEO, the 43-year-old Steinke looks tired: “If I knew when I started the company, that I would have to spend the next four years running after money, I would not have done it, for sure.” The honest statement is followed by descriptions of the German startup culture. It seems that finding investors in the country is not easy and involves “too much small talk.” Steinke doesn’t strike me as someone who would have problems with small talk: He is easy-going, talkative and quick to make jokes–it’s just that he has done more than his share of it and would probably much rather be skiing.

Jaakko Järvensivu

Steinke in the B.A.M. factory headquarters. PHOTO:

Jaakko Järvensivu

Bavarian skiing roots

We’re in Oberhaching, a small town with 13,000 inhabitants, some 15 km south of Munich, the capital of Bavaria. I arrived earlier today at the sleepy train station of Deisenhofen, from where Steinke and his 13-year-old docile mixed breed, Tapu, picked me up in Steinke’s white-colored T6-model Volkswagen van.

It’s here in small-town-Bavaria, where Steinke got his introduction to skiing at the age of three. When he was 15, he made it into the SC Hochvogel, a local cross-country ski team and developed into one of the top racers in the country. His racing career was cut short by glandular fever at age 19. Steinke started rock climbing and travelled all over Europe and even to California, in search of climbing spots. Climbing led him back to skiing and landed him a place in the Dynastar freeride team.

The team rider position didn´t include any financial compensation, so to make ends meet Steinke worked as a ski instructor and waited tables. He became a ski nomad and spent four European summers skiing in New Zealand. Over the years Steinke started to take more responsibility: The team rider stint at Dynastar changed into a team manager position and he started his own ski school in Munich.

Although Steinke was enjoying the benefits of being a freeride guide and ski instructor in Bavaria –he describes his company’s modus operandi as “picking up customers in Munich and driving to whichever ski area had good snow.” There was still one problem: fat skis. While in 2005 there were plenty of them on the market, the majority of them were, to use his own words “soft cucumbers.” Unable to find the kind of fat skis he wanted to ski on, Steinke decided to make them himself.

SKIER: Michael Normann | PHOTO: Jakob Schweighofer

It wasn’t just another one-man-garage-operation, the skis were manufactured in a defunct Kästle factory in Voralberg, Austria, and featured a solid, non-cucumber-like wood core and sandwich construction. Each model was named after a song. The Personal Jesus, for example, was a touring ski with a modern freeride shape. The skis were regarded as being innovative for the time, received good test results in German ski magazines and even won an ISPO marketing gold award.

Things were looking up. In 2009 Steinke sold his brand Mountain Wave to a German industrial safety company called Skylotec and was appointed as the development manager of the new company. According to Steinke, Skylotec had recently purchased the industrial side of the Swiss outdoor apparel company Mammut and wanted to become the German equivalent of Black Diamond. It didn´t work out. “They were based in central Germany and didn´t have a clue about skis, I was the only skier there,” Steinke now recalls. So, in 2014, he suddenly found himself unemployed.

The birth of the Pindung and BAM

It was a Sunday afternoon in 2014 when he got the idea: “The wings will come in from the front and we´re going to move the toe piece, so that the pins can come out, and we´ll use the DIN setting spring to lock the pins.” Steinke then called an old friend, mechanical engineer and skier Michael Kreuzinger, and explained the concept to him. “[Kreuzinger] thought it sounded like a good idea and that´s how it got started,” says Steinke.

The need for the idea occurred much earlier though. Around 2012 when Steinke was introducing the latest offering of his ski brand Mountain Wave to journalists, he ran out of test bindings. To solve the problem, he quickly bought some lightweight pin bindings and had them mounted to the test skis. Long story short, he didn´t like the way they skied: “I realized that, although you could tour with [pin bindings], doing proper carving turns on the slope was impossible, because the binding was fucking your skiing up!” While Steinke agreed that the pin system was the best solution to go uphill, he somehow wanted to integrate it into a normal binding.

Steinke observing the latest model of the Pindung. PHOTO: Jaakko Järvensivu

Concurrently, another slightly bigger alpine ski binding company was tinkering over similar issues. According to Amer Sports, its daughter companies Salomon and Atomic started a project called Safe and Light in 2012, which aimed to create a light TÜV-certified binding. In 2017 Salomon athlete Cody Townsend said the project was spurred in 2010 by conversations between him, Chris Rubens and a Salomon engineer. Instead of the regular three-year binding development process, it took Salomon seven years to finally release the Shift in 2018.

Meanwhile, Steinke founded B.A.M., together with Kreuzinger, in November 2014. Thanks to 3-D-printing, he was able to ski on the first prototypes in New Zealand by September of 2015. The trip was also used to film a promotional video, which was used in the crowdfunding pledge for the Pindung a month later.

The three-month crowdfunding proved successful as the company not only received the targeted 50,000 euros, but also another 70,000 from newly acquired silent partners. It looked like the self-titled “enduro binding” had hit a sweet spot on the market and the company was on a roll.

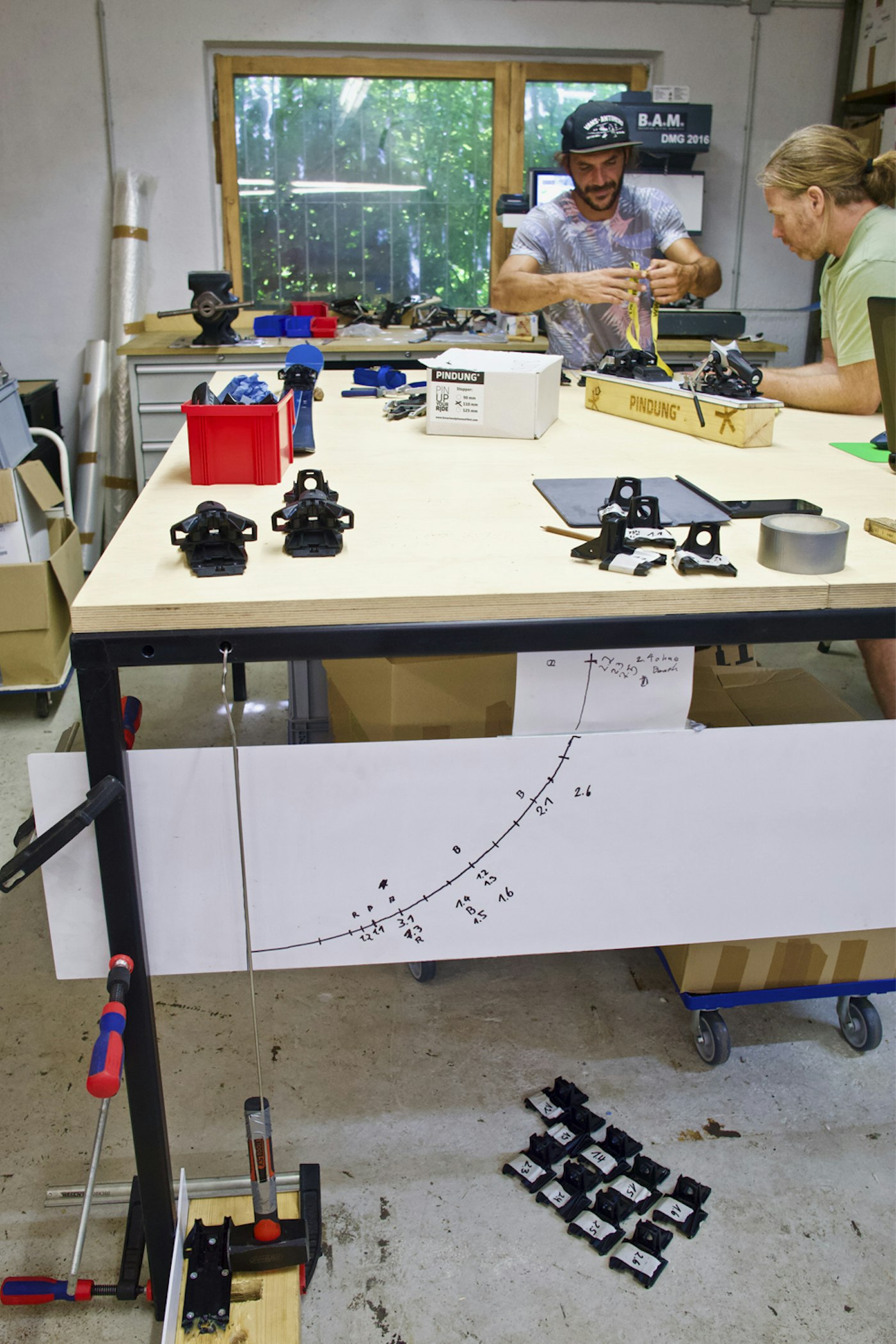

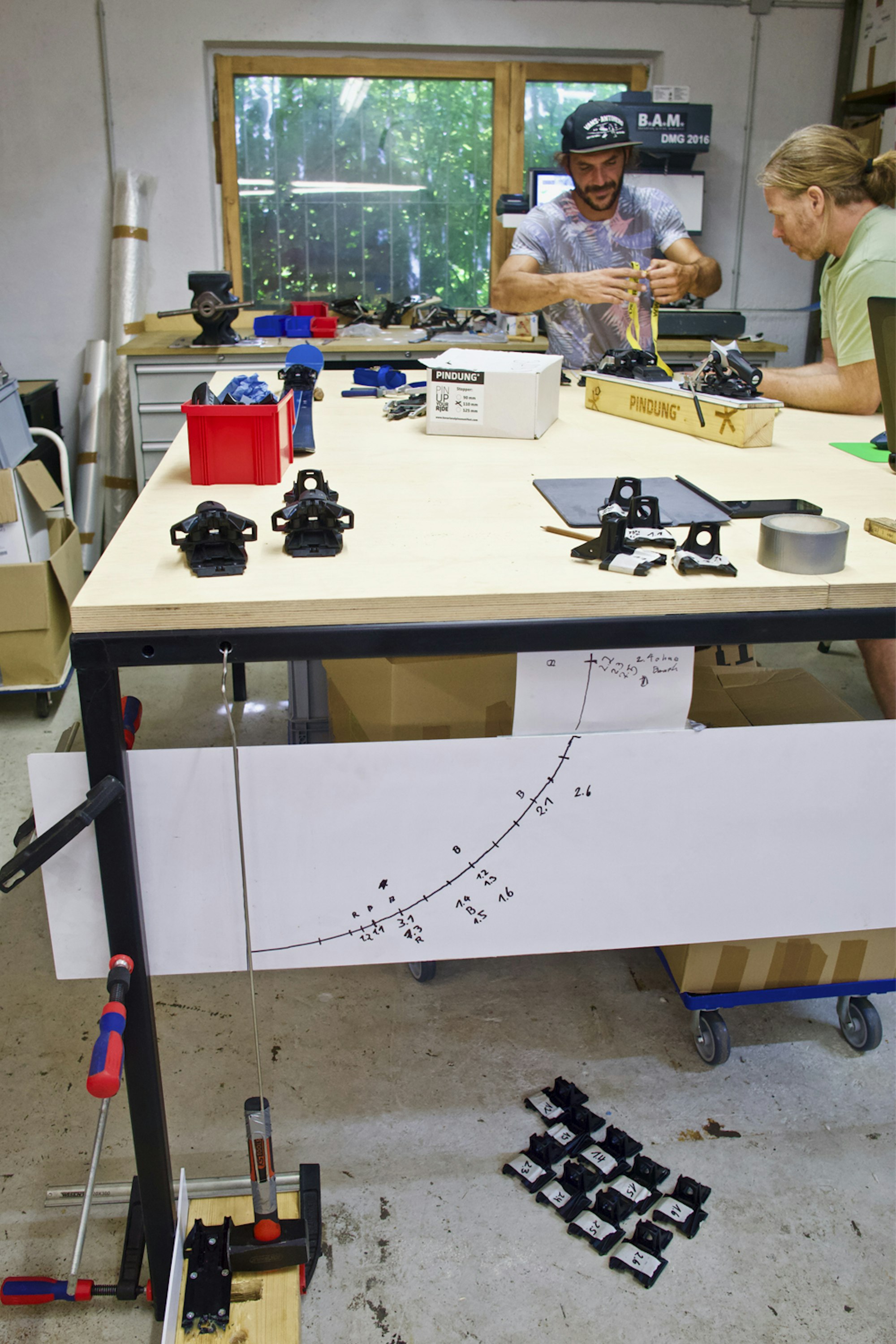

At the factory

Sandwiched between a railway track y-junction and the local soccer fields, these slightly run-down-looking warehouse buildings with fading yellow stone facades are now home to a cluster of companies and creatives, including Nico Cazek, the founder of Downdays Ski Magazine and a German off-road magazine, with their expedition-ready truck, complete with extra jerry cans and a snorkel, parked outside. Steinke leads me passed the offices and we enter into what looks like a large shed with tools and antiquated machinery. At the other end, behind the heavy plywood doors, is where the Pindung research and development process takes place.

The main room is pretty small with meticulously placed tools on one wall, an industrial shelf filled with boxes on the other, engineering machinery by the small window, and in the middle of the room, a large table with various binding parts and a laptop, all lit by bright fluorescent lamps.

Squatted next to the table is Michael Kreuzinger. Kreuzinger has dark surfer hair and a beard and is dressed in a colorful print t-shirt, beige shorts and a cap with the text ‘Vans Antihero.’

Kreuzinger in the B.A.M. Research and Development Factory. PHOTO: Jaakko Järvensivu

The tests

Behind Kreuzinger is a graph with an evenly rising curve and marked figures on a white carboard. I watch as he releases a sledgehammer hanging on a string from the table. It swings past the graph and hits a part of the toe piece fixed on the floor. The part connects the binding to the ski and Kreuzinger and Steinke refer to it as the mothership.

In the previous version of the binding, the mothership was made of a plastic called POM–a choice, which almost killed the company, that had set the 2019 ISPO as the Pindung’s new market entry target. Had their financial situation been better, they could have afforded to do more tests, but Steinke and Kreuzinger were running out of funding and faced a make-it-or-break-it situation: “We knew we had to be able to sell the product as fast as possible, that is why, instead of several, we decided to just do the first series as strong as possible,” says Steinke.

Just before the 2019 ISPO, however, Steinke managed to break the mothership of the binding while skiing moguls. After some hesitation, Steinke and Kreuzinger decided to cancel the market entry. It wasn’t an easy decision, but they couldn’t risk jeopardizing their key selling point: “We talk about a solid product, so it has to be solid,” says Steinke. Although the durability tests had been “on the limit,” according to Kreuzinger, normal skiing wasn’t a problem, even when using POM. Knowing what the limit value should be is the tricky part: “I think how big the maximum force with the DIN setting is and then decide how strong the part should be,” Kreuzinger explains.

Kreuzinger drops the hammer in a force test. PHOTO: Jaakko Järvensivu

When speaking about the forces, he gives an example of a man weighing 110 kilograms jumping off a cliff and the binding absorbing the impact. “I use all the modern equipment and programs in calculating the forces, but you then have to decide the scale, how big is the force scale and maximum impact,” Kreuzinger adds.

I later watch him use the equipment in a test, where a ski with the toe piece mothership mounted on it, is fixed into a simple-looking machine. A nylon webbing strap, tied between the top section of the machine and the mothership, starts pulling the part upwards. The monitor in the middle shows how the force used increases at a constant pace. First, the ski starts to bend and after several seconds part of the toe piece snaps off, whirling across the room. Kreuzinger, who now looks like a mad scientist with protective glasses on, is smiling. Thanks to the special additives inside the new material, PA6, it is proving to be three times stronger than POM.

Design and patents

There is one subject you just cannot leave out when talking about the Pindung, and that is the close resemblance of the toe piece to that of the Salomon Shift. The touring mode in both is activated by pulling a lever, the difference is that in the Shift, the pins are integrated in the wings, while in the Pindung, move through the toe piece, when activated.

The ultimate testing grounds for the Pindung. PHOTO: Joi Hoffmann

Steinke registered the first patent for the Pindung, with money received from a friend, in August 2014. While Salomon did file for their first patent on the Shift already in 2013, according to Steinke, the design wasn´t what the finished product looks like today: “They developed both the patent and the product over the course of time,” he explains.

While BAM came out with their toe piece design in October of 2015 with crowdfunding, it took Salomon another two years to publish theirs in the December 2017 press release of the Shift. This made some people question whether Salomon had in fact stolen Steinke´s idea. Steinke does not agree: “that´s bullshit, it takes four to five years to develop a binding like this–Salomon did their job and we did ours.” Steinke adds that Salomon probably wasn´t “too happy” about the Pindung crowdfunding campaign in the middle of their R&D process. He says that Salomon never contacted him though: “They always stop by at ISPO, but never really say much, with all the other companies, like Fritschi and Dynafit, we have a really good relationship.”

Friends and family – funding and responsibilities

Since the first patent Steinke has registered two additional ones, with the overall cost of the three equating to 150,000 euros–not a small sum for a company that has yet to sell a single unit. After the 2016 ISPO, The Pindung received an innovation funding from the Bavarian state, but to be able to cash it, Steinke needed to have an equal amount in his bank account, which led to a successful “friends and family” crowdfunding.

The friends and family, who invested in the company, received the same deal as the official silent partners would later: “For 10,000 euros, you get 40-50 cents for every sold binding, the pay-back can be fixed in years or one lump sum,” Steinke explains. Using this model, Steinke has been able to raise 300,000 euros altogether. When asked about the possible pressures the family-funding-model might put on your shoulders, Steinke talks through the investment stages in great detail, but in the end, doesn’t answer the question.

Steinke holds the latest version of the Pindung. PHOTO: Jaakko Järvensivu

Still, the pressure must be there. After the market entry failure at the 2019 ISPO, B.A.M. had once again exhausted their budget. The company had already ordered the parts for 1,000 bindings before the sudden need for material changes: “We could keep around 60 percent of those parts, the other 40 percent we had to throw away–it almost killed us,”Steinke admits. It turns out that material wasn’t the only problem. The company had decided to use the walk-to-ride standard for their toe plate adjustment, then, according to Steinke, the big companies suddenly decided to ditch the standard: “It will be all Grip Walk from now on and our plate is not Grip Walk compatible.”’

It was a dire situation, but a last-minute investment by a local plastic material supplier saved the company. “[The suppliers] have all supported us, giving us more time to pay the bills, encouraging us to get the company running,” Steinke describes. Surprisingly, thanks to the success of the automotive industry in Bavaria, Germany is actually one of the biggest producers of plastic parts globally. The abundance of cost-efficient suppliers means that 90 percent of the parts used to manufacture the Pindung will be made in Germany. Steinke assures, that the margin of the final product, with the suggested retail price of 499 euros, has been well thought over: “We already know it will work, but of course in the beginning, with lower quantities it is not as profitable.”

Finally ready for the market entry?

During our meeting in early July Steinke says that Kreuzinger has already come up with a “B.A.M. solution” for the Grip Walk problem, one that would allow you to switch from alpine to touring or Grip Walk boots without any tools. “We still have to test it though,” he adds. It means a hasty schedule for the planned October market release, but by now Steinke is already used to it and the glaciers in Austria are nearby.

After rounds of testing and tinkering, Steinke and Kreuzinger are ready to bring the Pindung to market. PHOTO: Jaakko Järvensivu

If it all comes together Steinke and Kreuzinger will have to start selling the bindings fast to pay the bills and the shares of silent partners and fulfill the pre-orders of the crowdfunding campaign. The company already has a Canadian distributor and two current retail orders, one of which is to a big shop in the Munich area where he has established good contacts over the years.

He reckons that the retail orders will account to the first 100 sold pairs. This time around Steinke trusts in the organic growth of the sales: “I sold promises for two or three years, it was really tough, even with my contacts,” he explains. The small size of the company could also be an advantage in the beginning: “As long as we sell 5,000-10,000 bindings next season, everything will be fine–the minimum target is 3,500 pairs,” he concludes.

When the binding is finally ready, B.A.M. will need to get the word out. Steinke says their main marketing tactics will be sponsored riders and social media: “We have to give away one hundred pairs –it’s the cheapest way of marketing.” He also hopes to receive good feedback from magazine and online test coverage. And of course, the huge success of a very similar product, the Salomon Shift, doesn’t hurt either.

Could the Pindung be the iPhone killer?

If Shift is the iPhone of the ski industry, could the Pindung be the iPhone killer? Despite the similarities between the toe pieces, there is one major difference in the designs and that is the use of a Look Pivot-style heel piece in the Pindung, which, according to Steinke, could play to their advantage: “Due to my history with the Dynastar/Look/Lange freeride team, I knew that when it comes to off-piste skiing the Pivot is state-of-the-art. I wanted to have a turntable heel piece.”

The max DIN setting of the Pindung will be 14, compared to the Shift´s 13. Steinke thinks that the flexibility of the turntable heel allows you to ski with a smaller DIN setting though: “I skied the Look Pivot around nine and a half, and I’m heavy”.

SKIER: Jakob Schweighofer | PHOTO: Joi Hoffman

But the turntable heel piece also adds to the weight. Instead of the sub-1,000 grams Steinke was talking about at the 2016 ISPO, the final product will weigh around 1,300 grams per unit–is it too much? While Steinke thinks weight matters, according to him, its importance has been over-emphasized. Steinke sees a similarity between touring with a pin binding and pulling a suitcase on wheels: As you´re no longer lifting the weight, it doesn´t really matter whether the system is a little heavier.

Instead of a touring binding, Steinke likes to call the Pindung an enduro binding, referring to mountain biking, where over the years the focus on bike designs has shifted from weight-obsessed to downhill performance. In his opinion, the majority of skiers are skiing all-mountain skis and boots, mostly inbounds, from where they venture off-piste when the conditions are right. As most skiers obviously don´t want to compromise the downhill performance of their skis and boots, why should they do it with their bindings?

The creators proudly stand with their mounted Pindungs. PHOTO: Jaakko Järvensivu

It’s already late afternoon and I will soon need to take a train back to Munich, from where I will continue over to Salzburg for a much-anticipated holiday with my family. For Steinke, it’s another story. Although he wishes to squeeze in a quick mountain biking trip with his girlfriend, the main focus of the summer will still be on the Pindung. Tests on the new PA6 material and the Walk-To-Ride compatible toe plate system, together with preparations for the assembly, logistics, sales and marketing, will all have to be carried out before the planned October market release.

With last season’s failed market entry still fresh behind them, Steinke and Kreuzinger know they have to make this one count. They walk a tightrope, but seem confident, that they will make it. At the moment they may still be the unknown startup underdogs of the ski binding business, but that could change during in the coming ski season. As if reading my thoughts, Kreuzinger´s last words when I´m shaking hands with him on my way out are: “I hope you make us famous!” They are soon followed by guffaw by both him and Steinke.