Building skis is not rocket science. Nowadays, the same basic construction principles are applied to each new set of boards, no matter the manufacturer. Sure, many brands apply flashy buzzwords to their various technologies, and we understand that can be confusing. So, we’re here to help.

Dive headfirst into the info outlined in this post, and you won’t have any excuse for playing the card of ignorance when it comes to your gear. Spend a few minutes familiarizing yourself with the terminology, materials and construction techniques associated with your precious skis, and remember: Someone out there poured blood, sweat and tears into designing and building your sticks. These individuals rely on intricate subtleties of construction to bring you a product that caters to your specific skiing style. Only after spending an unfathomable amount of time tweaking and prototyping to achieve the desired build will a manufacturer present a product to you. Enlightening yourself with this information is a simple of way of saying, “Thanks!”

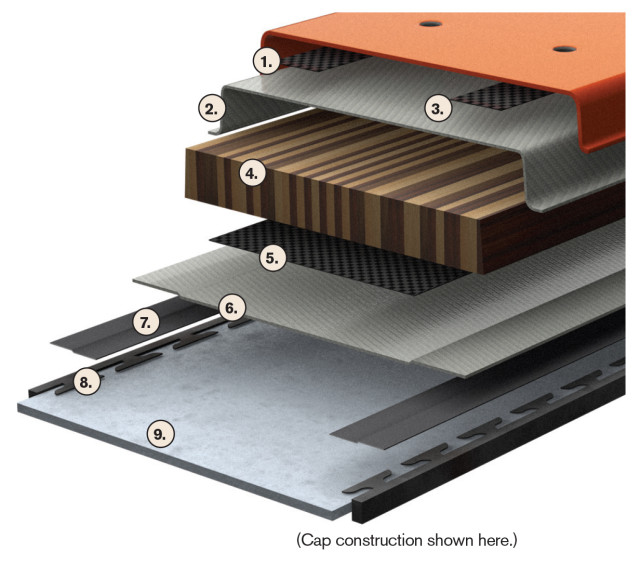

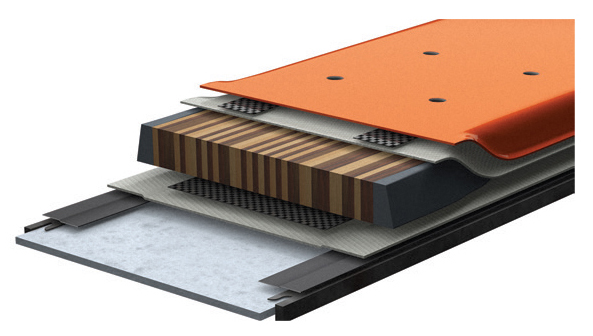

Ski Construction:

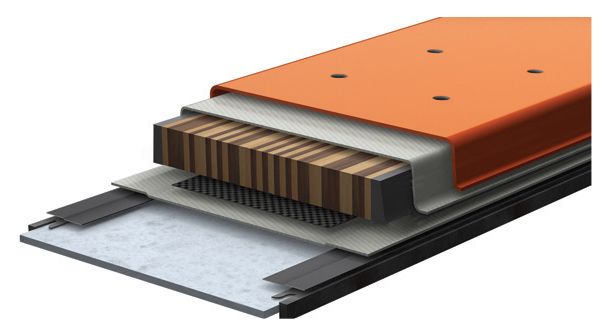

Infographic above: 1. Plastics | 2. Fiberglass | 3. Carbon | 4. Core Material | 5. Metals | 6. Fiberglass | 7. Rubber | 8. Steel Edges | 9. Base Material

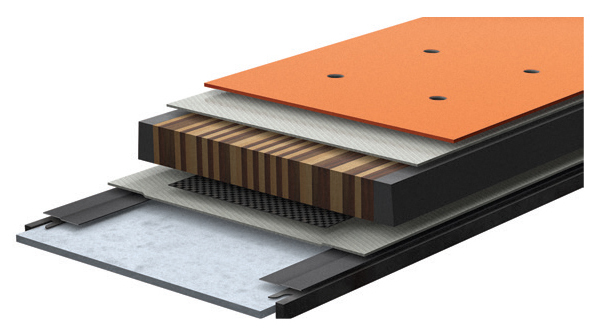

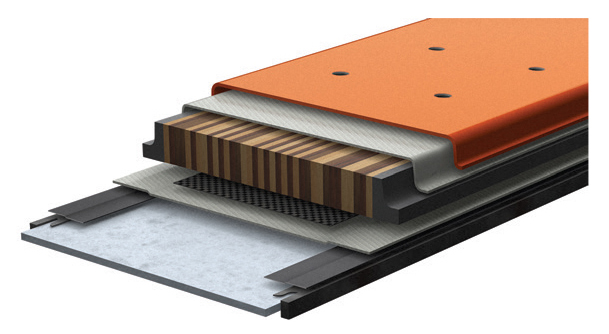

Sidewall Construction:

Cap: Cap construction entails the topsheet folding down over the edges of the ski to protect the core materials. This is an economic build and provides easy turn initiation, while its rounded top corner helps deflect sharp objects, yielding a more durable ski. Cap construction gen- erally provides weight savings due to a lack of heavy sidewall materials running the length of the ski.

Sandwich: The core materials of the ski, such as wood, fiberglass, carbon fiber, Titanal, etc., are layered like a sandwich and then wrapped by a topsheet, base and plastic sidewalls, commonly built with ABS or P-Tex. ABS is a medium strength, relatively affordable option, while P-Tex is extremely abrasion and impact resistant, although it’s pricey. This design provides unrivaled power transmission to the edge of the ski.

Half Cap: This technique is a fusion of cap con- struction on the top half of the ski with sandwich construction on the bottom for the best of both worlds—solid power transmission to the edges plus a light- weight and snappy feel.

Hybrid: This technique is a fusion of cap con- struction on the top half of the ski with sandwich construction on the bottom for the best of both worlds—solid power transmission to the edges plus a light- weight and snappy feel.

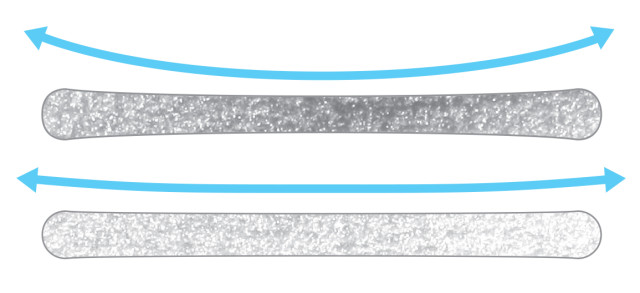

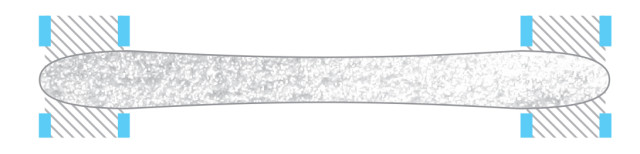

Rocker and Camber Profiles:

Regular Camber: A ski utilizing regular, or natural, camber has full edge contact with the snow when engaged by the skier’s weight. The result is maximum power transmission to the edge throughout a turn.

Reverse Camber: A concept introduced to the ski world in 2001 (thank you, Mr. McConkey), reverse camber, aka rocker is the opposite of regular camber. In this construction, the ski has far less edge contact with the snow, making it easy to pivot and surf the mountain. The early rise in the tip also helps with turn initiation as well as flotation in soft snow.

Hybrid: A growing majority of skis utilize a combination of reverse and traditional camber. This usually comes in the form of early rise tips and tails and camber underfoot, often spelled out as “rocker-camber-rocker.” This gives the skier the benefits of both a traditional and reverse cambered ski.

Core Construction:

The materials built into the core of every ski determine its character and flex, and thereby how it will behave on snow. The essential ingredient of the vast majority of skis (any worth riding) is wood. Each type yields a noticeably different feel on the snow. Beech, maple, ash and fir, for example, are denser and burlier than other types and provide great torsional rigidity and stability. On the other hand, paulownia is ultra-lightweight but doesn’t dampen vibrations as well as other woods. Sitting in the middle are aspen, poplar and bamboo which have a solid balance of weight with dampening and pop.

Manufacturers regularly employ a combination of different types of wood, capitalizing on their various properties. This allows builders to fine-tune the ski’s characteristics, giving different strengths and flexes to certain areas of the various models.

Once a wood, or combination thereof, has been selected, various materials are epoxied around the core to calibrate performance and purpose. Titanal and other metals, for example, bolster rigidity. Fiberglass, which is more affordable, is often braided around the core to achieve this end, as well. Fiberglass strength is associated with the way it’s weaved. “Bi-axial” and “tri-axial” are the most common weaves and mean that the fiberglass is running in two and three directions, respectively. The more fibers that are running across the ski, the better the torsional rigidity will be.

Carbon has a high strength-to-weight ratio and is regularly added to the core for a boost in stability without increased weight. It’s a bit pricier, though, and manufacturers often employ carbon “stringers”—thin strips of the material added to the wood—to reap its benefits while keeping costs low. Another often-used material is aramid, commonly known as Kevlar. While the fiber has a bit of a higher strength-to-weight ratio than fiberglass, it’s mostly used for its ability to dampen vibrations. Adios, tip chatter!

Turn Radius:

Think back to the glory days of high school geometry. The radius of a circle is the distance between the center and the perimeter and is also referenced when dis- cussing a ski’s turn radius. Theoretically, skiing a perfect circle around a designated center point on various ski models would generate several different sized circles. The sidecut and the stiffness of materials in the ski determine the size of the circle. Less sidecut and stiffer materials create a larger circle and a larger turn radius, while deeper sidecut and softer materials produce the opposite.

Lower radii skis, generally 16 meters or lower, are great for carving quick turns down the frontside. Radii between 17 and 22 meters are meant for skiers attacking a variety of terrain all across the hill, including the park. A turn radius of 22 meters or above is great for arcing big turns down steep, deep faces.

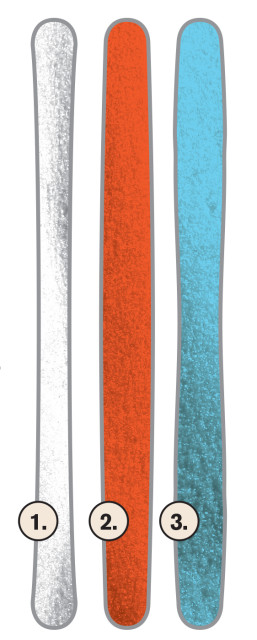

Sidecut:

1. Traditional: This shape maximizes edge contact with the snow, delivering exceptional carving capabilities.

2. Reverse: This design is built to handle deep snow with ease. It pivots effortlessly, and its tapered extremities help eliminate hooking in powder.

3. Multidimensional: Traditional sidecut underfoot ensures easy carving, and a tapered tip and tail keep a ski light and agile.

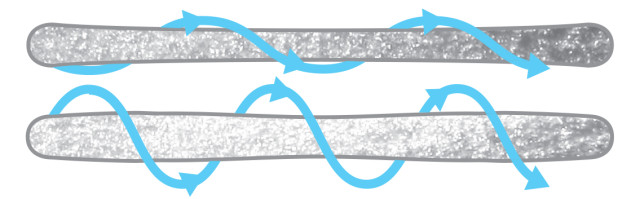

Torsional Rigidity:

Torsional rigidity gauges how resistant a ski is to twisting. This factor comes into play mostly when you’re railing high-speed turns on hardpack. A sufficiently rigid ski will provide effective edgehold throughout your turns.

Taper:

Taper is the thinning of width toward the tip, tail or both ends of the ski. Rockered skis often feature a bit of taper because their effective edge length is shortened due to the ski’s early rise. With a “shorter edge,” there’s no reason to have the widest point of the ski be the very tip or tail. Tapering is then implemented to avoid hooking in softer snow.